AUSTIN, Texas –– Polling places mysteriously ran out of ballots when Mexican Americans showed up to vote. Ads on Spanish language radio threatened fines and imprisonment to those who voted without first properly registering to vote. Illiterate voters were not given assistance at the polls.

These were just a few examples of tactics used to keep Mexican Americans from voting in elections after the Voting Rights Act was passed given by scholars and activists at a two-day conference in Texas on the struggle for Latino voting rights.

The Voting Rights Act protections are weakened today after a 2013 ruling by the Supreme Court that gutted the act, experts said, and new tactics are taking their place to suppress Latino votes as the population grows and becomes more politically potent.

Challenges being seen today are the elimination of early voting days; voter identification requirements; attempts to return to at-large districts and cuts to language voter assistance, said Vilma Martinez, a former general counsel for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, who argued several voting rights cases that helped extend the Voting Rights Act to Latinos.

“What I see today are new variations on the theme of diluting and discouraging the Latino and minority vote,” said Martinez, the opening speaker at the conference titled, “Latinos, the Voting Rights Act and Political Engagement” held at the University of Texas at Austin.

The conference is intended to bring to light the intimidation, discrimination and at times violence Mexican Americans and other Latinos faced as they tried to exercise their right to vote even a decade after the signing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

“There is a huge lack of awareness of the effort and the contributions and sacrifices Latinos have made to become politically engaged just to cast a vote,” said Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez, a UT journalism professor who organized the conference.

“It meshes well with how Latinos are under attack now politically. I think people think that we have just arrived and we have just now become mobilized, when Latinos have been mobilized politically for many generations, when they’ve given a lot,” said Rivas-Rodriguez, author of “Texas Mexican Americans & Postwar Civil Rights.”

Ari Berman, a contributor to The Nation magazine and author of “Give Us The Ballot," told the story of political activist Modesto Rodriguez from Pearsall, Texas, who tried to mobilize Chicano political power in the state.

At the time, ballots were only in English in Frio County, which includes Pearsall. The English-only ballots served as a defacto literacy test since Spanish was the first language of most of the Latino residents, Berman said.

After Rodriguez testified to Congress about the discrimination, he was at a Frio County bar that was raided by local officials. Rodriguez was clubbed over the head with a large flashlight and taken to jail. The family was so afraid Rodriguez would be killed at the local hospital he had to be airlifted to San Antonio for care.

“This was an incident that didn’t get much attention at the time. This was not like Bloody Sunday. No one knew about it. But it showed the risks Chicanos faced in places in Texas when they tried to get involved in the political process. And it showed the need … for the expansion of the Voting Rights Act,” Berman said

Luis Fraga, a University of Notre Dame political science professor, said the history of the movement to expand the Voting Rights Act is grounded in the state of Texas.

Al Perez, the attorney who first approached Martinez about getting MALDEF to fight for the expansion of the Voting Rights Act for Mexican Americans, was from Brownsville, Texas.

Perez’s family was poor and so was their community. Although Perez's parents and grandparents were born in the U.S., they spoke only Spanish and Perez realized they had difficulty reading their ballots.

A military veteran who attended George Washington Law School, Perez ran the D.C. office for MALDEF in 1974. That’s where he became aware that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which applied to states with a history of discrimination, was up for renewal for the third time since the act became law.

He enlisted the help of the pro bono division of Hogan & Hartson, where he had once interned.

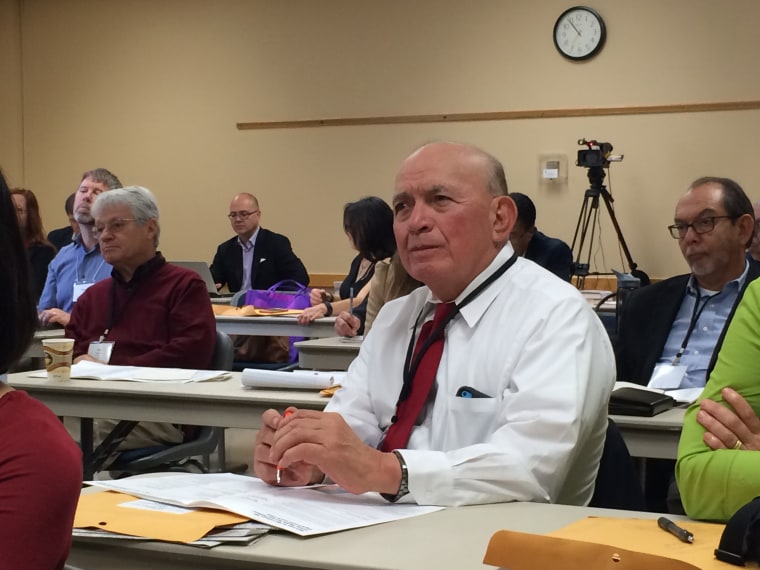

“Al decided Mexican Americans should be included in this new extension of the act,” Fraga said of Perez who was in the audience during the panel discussion.

Although the discrimination existed in the state, Texas had been excluded from the Voting Rights Act Section 5 requirement, even though it had a significant history of voting discrimination against blacks and Mexican Americans.

“Texas was a primary focus of the 1975 extension,” Fraga said.

To get Texas covered, Perez and other attorneys used “language minorities” to challenge Texas discriminatory practices and persuade Congress to expand the act.

“When you read the actual testimony (before Congress), what you find is that most of the testimony that was presented as evidence of discrimination didn’t deal with language, portions of it did,” Fraga said. “But most of it dealt with other aspects of voting rights discrimination” such as use of at-large elections, lack of voter registration, vote dilution, denying candidates who wanted to run for office the opportunity to run.

“Language served as a catalyst to (challenging other voter) discrimination" in Texas and other places, Fraga said.

As the Latino population has grown, fights against barriers to Latino political participation have continued.

The recent election of three Latinas to the seven-member Yakima, Washington City Council followed a long fight against at-large district elections. They are the first Latinos to serve on the council.

A lawsuit alleging voter dilution under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act overturned that system and districts were drawn that created at least two with large Latino populations and at least two others with enough numbers to potentially elect a Latino to office.

Analysis by Fraga and University of New Mexico doctoral student Vickie Ybarra also show increases in registered voters with Spanish surnames.

But those victories have become more difficult with the Supreme Court decision that gutted the Voting Rights Act and the growing Latino electorate, conference speakers said.

“What we see is that Hispanics are as much of a target as African Americans,” Berman said. “If you look at voter ID laws in Texas, or you look at proof of citizenship laws in Kansas for voter registration or you look at voter purges in Florida, these are aimed expressly at the fastest growing demographic.”