In what could be a blow to hundreds of young baseball pitchers, a new study being presented Tuesday debunks the notion that Tommy John surgery is an easy way to make it to the major leagues.

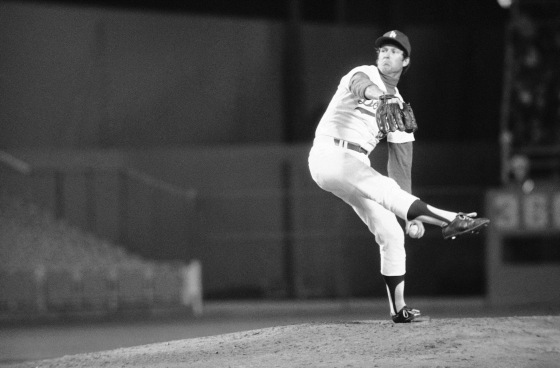

After his elbow blew out during the 1974 season, Los Angeles Dodger pitcher Tommy John faced the end of his career. But a revolutionary surgery created by Dr. Frank Jobe (who died last week) to reconstruct the ulnar collateral ligament not only put him back on the mound, but helped him have three 20-game winning seasons with the Dodgers and the New York Yankees. He pitched for 13 more years.

It was a remarkable story, but it had an unintended consequence that plays out often in the offices of top sports orthopedic surgeons.

“We have a number of high school and collegiate athletes who seek out Tommy John surgery thinking they’ll perform better,” Dr. Bill Moutzouros, team doctor for the Detroit Lions and the residency program director in orthopedic sports medicine at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit told NBC News.

Dr. Christopher Ahmad, the head team physician for the New York Yankees and the chief of sports medicine service at Columbia University Medical Center, sees the same pattern. Young men with no serious injury, or their parents or coaches, request Tommy John thinking they’ll get become a better pitcher.

“I routinely see kids … who feel like they’re not progressing and they want to get that performance kick,” Ahmad said. But according to the findings of the study performed by Moutzouros and colleagues and presented Tuesday at the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons in New Orleans, those wannabes could be making a grave mistake.

“I routinely see kids … who feel like they’re not progressing and they want to get that performance kick."

Moutzouros tracked the statistics of 168 Major League pitchers who had the surgery for three years before the operations and three years after a return to pitching, and found performance declines in key statistics.

As other studies have shown, the surgery was very successful in returning pitchers to the majors. After the surgery, 87 percent pitched in the majors again.

But their stats suffered. Earned run average (ERA) rose from a 4.15 average the three years before surgery to 4.74 after. Walks and hits per inning rose, too, from 1.4 to 1.48. Winning percentage decreased from 45 to 42 percent. When compared to a control group of pitchers matched for age, the reconstructed pitchers actually had a better ERA during the first year back, but the control group pitched more innings and had a better winning percentage.

The trend for who got the surgery, Moutzouros said, was for “younger guys who came into the leagues earlier. They need the surgery earlier.” Most were starters, not relievers.

Another study published just this month in the American Journal of Sports Medicine found that pitchers who had the surgery “had better results in multiple performance measures.” But that study tracked stats for the one year prior to surgery and the one following return to play. Often, pitchers begin to break down — and show poor results — in the year prior to surgery. That’s why they get it. Ahmad said he was presenting data at the meeting that jibes with the Moutzouros study.

Ahmad also tracked velocity of pitches and found that pitchers who got Tommy John surgery lost roughly 2 miles per hour off fast balls. That’s a big number in the Major Leagues.

Ahmad is happy to get the message out that Tommy John surgery is no way to become a better pitcher. Too often, he said, young athletes “wind up needing it because they abuse their arms. They say ‘I can throw through pain, ignore the symptoms because if I break down, I’ll just get surgery and then I’ll be even better.’”

In fact, recovery takes at least one year, and as this new research shows, a pitcher isn’t likely to be any more fearsome than he was before.