PICHER, Okla. -- Thirty years and hundreds of millions of dollars since work began to clean up this former lead and zinc mining boomtown, progress is still being measured in inches or feet. That gauge is provided by the towering but slowly diminishing piles of “chat,” or tailings, that still loom over what is now a virtual ghost town.

Picher, which in its heyday in the 1920’s boasted a population of nearly 20,000 people, no longer exists as a town. After being labeled one of the most polluted places in America by the EPA, declared a federal “Superfund” hazardous waste site, and also getting hit by a destructive tornado, it ceased municipal operations in 2009.

That same year, Picher-Cardin High School, perhaps best known for its distinctive “Gorilla” mascot, graduated its last class of 11 students.

Finally, in November 2013, after nearly all of its residents had accepted federal buyouts on their homes and moved away, the town formalized the obvious -- and dissolved its charter.

Today, there are only about 10 hardy souls left in Picher to watch as the clean-up slowly carves away at the dozen or so remaining piles of chat and restores Tar Creek, whose waters still run red from heavy metal runoff, to some semblance of its former self. If their health holds out, they likely have another 20 or 30 more years to take in the slow-motion show in this quiet northeastern corner of Oklahoma, near the Kansas and Missouri borders.

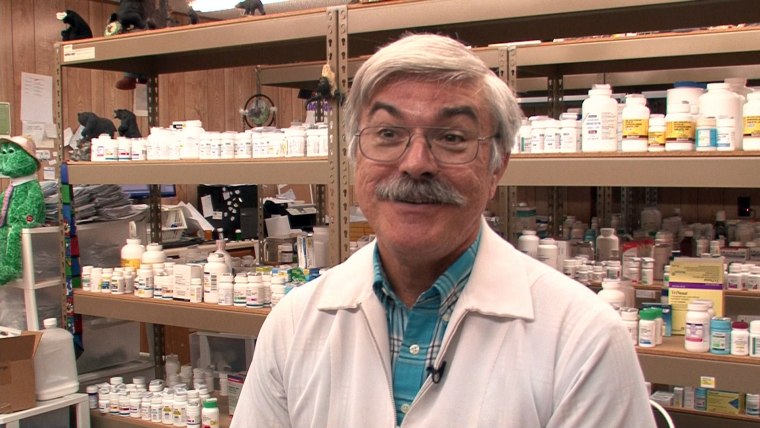

Among those still living and working in the town is 59-year-old Gary Linderman, who has owned and operated the Ole Miner Pharmacy on U.S. Highway 69 for 16 years. He first came to Picher in 1975, when he went to work as a student extern for the previous owners of the pharmacy. Despite the hardships visited on his town over the last century, he senses a change of fortune in the wind.

“I think there’s going to be a resurgence in Picher -- in time,” he said.

That time is still some way off, according to Bob Sullivan, the Environmental Protection Agency site manager for the cleanup.

He says the federal government has spent $301 million since Picher and the surrounding areas were declared a “Superfund” site in 1983, when the town’s toxicity levels surpassed even those of the infamous Love Canal site in upstate New York in the mid-1970s.

Another $178 million is expected to be spent on the cleanup over the next 20 years, Sullivan says.

Most of the remediation work going on now involves excavating contaminated sludge and remodeling stream beds with clean soil, adding water treatment units, collecting clean water from existing uncontaminated wells and distributing it via a pipeline network to the few remaining homes and farms in the area, while also drilling new wells. Contractors continue to chew away at the chat piles as well, although the pace of that work can appear slow, since down-river Oklahoma residents have to wait for contaminated areas of Kansas and Missouri to be cleaned first.

That’s because cleaning up the Picher area is just part of the challenge. The so-called “Tar Creek Superfund Site,” which covers 40-square miles and also includes the towns of Quapaw, Commerce, Cardin and North Miami, is just one of four “sub sites” within what is called the “Tri-State Mining District,” an area that covers 2,500 square miles and extends into southeastern Kansas and southwestern Missouri. Rivers and soils in Kansas and Missouri are also polluted by toxic runoff, and work needs to continue there to prevent that pollution from undoing the progress that’s been made in Oklahoma.

The length of the cleanup in Picher is largely due to the long period of time that environmental damage was inflicted on the town and its surroundings.

Starting in the late 19th century, Picher was at the forefront of Oklahoma’s lead and zinc mining industry. At the height of the boom, in the 1920s, it had over 14,000 resident miners and possibly another 5,000 townspeople.

During both World Wars, 75 percent of all the bullets and bombshells expended by American troops were made from metals mined in the region.

The chat piles – mountains of crushed limestone, dolomite and silica-laden sedimentary rock that sometimes rose to heights of 300 feet or more – were the leftovers after the metal ore was separated.

Jack Greene, 91, worked in the mines beneath Picher from 1938 to 1941, before he was drafted into the Army during World War II. He remembers tremors from the mines shaking pencils off the desks at the high school. "They let people destroy this country from being so greedy," he said, describing the practice of removing pillars of rock originally left in place by miners to support the caverns they'd dug out.

By the time mining ceased operations in the late 1960s, there were an estimated 178 million tons of chat, mill sand and sludge in about 30 piles scattered in and around Picher. As the town dwindled to fewer than 2,000 residents, the chat piles became an integral part of the local culture. Families picnicked on them, 4-wheelers rode their bikes up and down them, while the local high school track team trained on them.

They knew to avoid Tar Creek after the waters started running red in the late 1970s – the result of pollution from heavy metals like lead, zinc, cadmium, arsenic, iron and manganese – but folks were slow to realize the extent to which the “chat” piles were slowly poisoning them.

A few local doctors did notice that kids in Picher seemed to get sick often, and teachers observed that their students always seemed to be lagging behind those in other parts of the state in testing. But no one linked the high lung cancer rates, cases of hypertension, respiratory infections and high infant mortality rates to the “chat” piles in Ottawa County.

Then health studies from the University of Kansas School of Medicine via an EPA Technical Assistance Grant in 2004 produced some alarming statistics. Some rates of disease in the three state mining area were 20 to 30 percent above average, but the rate of the chronic lung disease pneumoconiosis, for example, was 2,000 percent higher.

“People didn’t connect any of this to the mine,” said Rebecca Jim, executive director for the Local Environment Action Demand (LEAD) agency, a local, nonprofit environmental group. “They didn’t go, ‘This is causing me to get sick.’ Lead poisoning in children, you can’t tell it. They don’t walk funny. They don’t walk with a limp. With lead poisoning, it’s so subtle you don’t notice it unless it’s an extreme dose.”

Karen Harvey, 53, lived in Picher from 1960 to 2002, and as a kid she played on chat piles and swam in tailings ponds. "We'd go swimming in them and our hair would turn orange and it wouldn't wash out," she said. At age 18 she had surgery to correct bone growth in her ears that interfered with hearing. Noting that she's also dyslexic and was recently tested with an I.Q. of 65, she said she's starting to wonder if her childhood in Picher contributed to her health problems. "I don't know if that has something to do with it or not," she said. "I'm just figuring it out as I get older."

The federal and state governments were slow to appreciate the hazard as well.

After tests ordered by the state of Oklahoma showed heavy metals contamination in 1980, the EPA plugged wells and studied the local aquifer more closely. By the mid-1990’s, crews started removing six to 10 inches of surface soil from residents’ yards, hoping this would limit resident’s exposure to chat dust and contaminated drinking water.

By the early 1980’s, however, it became clear that half measures would not suffice and that the health risks were far greater than initially thought.

Meanwhile, another mining-related problem continued wreaking havoc in Picher. So many tunnels had been carved beneath the town that sinkholes began to appear as mines were abandoned, and officials realized they couldn't guarantee the safety of residents. An Army Corps of Engineers study in 2006 showed that almost nine out of 10 buildings in town were susceptible to sudden collapse. The federal government began making buyout offers to residents and business owners, many of whom were reluctant to leave a place that had been called 'home' for several generations.

The final blow to the town was delivered in May 2008, when a powerful EF4 tornado decimated 20 blocks of homes and businesses, killing eight residents and injuring 150 others.

After the tornado, nearly all of those who had rejected the buyouts were ready to concede that maybe it was time to move on.

Linderman was one of the few who didn’t. He says he didn’t want to leave his home and the government wasn’t offering all that much anyway.

So he continues to commute from his ranch near the small town of Welch, Okla., occasionally staying in the apartment he keeps at the back of the pharmacy. Even though the town of Picher no longer exists, his business is still on the electrical grid and he gets his water from wells that are tested and serviced by the nearby Quapaw tribe.

He says he believes the water is safe and that he has no concerns about his health -- “not one bit.”

Even though he’s very nearly the last man standing in town, he says business is still good, with former neighbors driving extra miles to pay a visit and pick up their medicines.

Why does he stay?

“Well, I’m very person-oriented and Picher, the people here are a very close-knit family, as I call it,” said Linderman. “They’re not just a clientele, they’re friends."