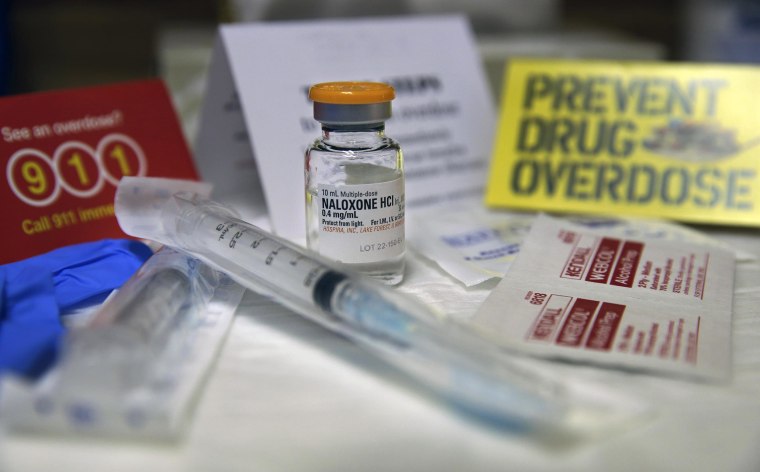

OCEAN COUNTY, N.J. — The opiate-blocker naloxone is one of the year’s most celebrated drugs, breaking into the mainstream as a magic-bullet antidote that yanks overdose victims from the brink of death with a shot of nasal spray or an intravenous injection. Police take it on patrols. Emergency medical technicians keep it in their ambulances. Ordinary Americans are stocking their medicine cabinets with it. Because of it, hundreds of people who might have died this year from taking too much heroin, Oxycontin or similar painkillers remain alive.

But the lifesaving medication is not a cure. After it has done its job, overdose survivors are left with their cravings intact. Without follow-up care, they are likely to keep feeding their habits, putting them at risk of another overdose, one that could kill them. Treatment, however, can be very difficult to find.

Lying in the emergency room after being revived, many addicts say they experience a fleeting moment of clarity that makes them receptive to help. But that potential is often lost in a patchwork healthcare system that gives survivors little incentive to change. Many walk out of the hospital with just a list of treatment options on their discharge papers, researchers and health care workers say.

“There are little windows of opportunity with an addict, little windows where I wake up and say, ‘I can’t f---king do this anymore. Either I got to die or please help me,’” said Kathleen, a 31-year-old mother who was saved by naloxone-wielding paramedics in October in Lakewood, a suburban community in Ocean County, which has become an epicenter of America’s heroin and opiate epidemic. She spoke on condition that she would be identified only by her middle name. “That window will last for four hours. Then somebody will call and be like, ‘I got some s—t.’”

Who goes to treatment and who goes straight back to drugs is difficult to determine, because overdose patients are rarely tracked. That has been the case in Ocean County, where heroin and opiate-related deaths more than doubled in 2013, authorities say. The spike, part of a national outbreak caused by a mass migration to heroin by people who’d gotten hooked on prescription painkillers, surprised many people, including the county’s top law enforcement officer, Prosecutor Joseph Coronato. He took office in March of that year, just as the numbers were rising. At one point in those early weeks, nine people died of overdoses in as many days. “All of a sudden, every day I’m getting another overdose,” Coronato recalled. “I’m saying, ‘What? How can that be?’”

Coronato had his staff start a database in hopes of finding a way to attack the problem. Then he began researching what police were doing elsewhere. That’s how he learned of naloxone.

The drug, also known by its trade name, Narcan, had been around for decades, injected with needles by paramedics and emergency room doctors. It began to be used more widely in the early 2000s, after healthcare professionals figured out ways to administer it as a nasal spray, making it easy for just about anyone to use. Activists distributed it to addicts. Cities began to experiment with equipping cops and EMTs. Then came a nationwide surge in overdoses from heroin and other opiates. That sparked a broader push to put naloxone into more peoples’ hands. It remained expensive and difficult to obtain, but the cops who used it raved about watching victims wake from unconsciousness almost immediately.

Coronato pushed for a pilot nasal-naloxone program in Ocean County, which began in April. Since then, more than 120 people have been saved by a local cop or EMT. Fatal overdoses, meanwhile, have dropped from 112 in 2013 to 78 so far this year. That pilot has now been duplicated elsewhere in the state. Its popularity has also fueled a wave of naloxone giveaways directed at the public—addicts’ friends and loved ones, mainly. The idea is to make it as ubiquitous as the EpiPen, which is used on people suffering potentially fatal allergy attacks. In April, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved another option, a device that injects naloxone into muscle or under the skin without using a syringe.

While tracking this year’s naloxone “reversals,” Ocean County authorities began noticing “repeat customers,” addicts who’d overdosed, were saved, resumed their habit, overdosed again, and were saved again. It turned out that few victims were getting steered to treatment. Maybe someone was lucky enough to find a bed in a residential treatment facility, while others got accepted into an outpatient program or methadone clinic. But these were case-by-case efforts; there was no organized system in place to direct victims to follow-up care, Coronato’s office said.

Kathleen, for example, was released from the hospital in early October with a note in her discharge papers to consider treatment, and the suggestion to scan the yellow pages for a facility. Fortunately, she was already in an outpatient program, and was able to return. But what about an addict who wasn’t familiar with the system? “The motivation of that person to actually call all these places to try to find where they can get in the soonest is not realistic. That’s not going to happen,” Kathleen said.

A law-and-order man, Coronato initially viewed the problem through that lens: if addicts weren’t getting better, they’d be more apt to “steal and deal.” But he needed partners in the local healthcare system, including hospital administrators, addiction specialists, and advocates. That quest thrust them into a burgeoning field of medicine that treats substance abuse like a public health crisis by focusing on education, prevention and a continuum of care. “There’s a growing understanding that this is a chronic disease that needs to be managed, like heart disease,” said Ed Bernstein, a veteran emergency medicine physician at Boston Medical Center.

Bernstein pioneered a program in the mid-1990s that screened patients who exhibited signs of substance abuse—people at clear risk of doing further harm to themselves and others, and becoming frequent visitors to the emergency room. The goal was to catch them during those small windows of opportunity and motivate them to seek treatment. The effort relied on a team of “health promotion advocates,” many of them recovering addicts, who conducted brief interviews with patients before they left the hospital.

That program, called Project Assert, has grown from about 3,000 patients screened in its first year to more than 5,000 annually. About a half request placement in a detox facility, and of those about 60 percent get placed, Bernstein said, a rate that reflects both the dearth of options and the severity of the disease. “But we never give up,” Bernstein said. “We keep trying.”

Project Assert was the first of a treatment model, since researched and refined, that came to be known as Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment, or SBIRT. It has been adopted by a growing number of healthcare systems around the country, including Bon Secours Hospital in Baltimore, Wilmington Hospital in Delaware, Yale-New Haven Hospital in Connecticut, and Denver Health Medical Center in Colorado.

Lynn Fahey, the CEO of Brandywine Counseling and Community Services, which helped develop the Wilmington program, said these projects represent a shift in thinking on addiction in a society that traditionally viewed it as a failure of will, and as a crime instead of a disease. “But the pill epidemic has brought the face of addiction to a new population, and this population is advocating louder and stronger for treatment and is helping to reduce the stigma,” she said. She cited as an example the Affordable Care Act, which mandates coverage of substance abuse treatment.

In Ocean County, it took the successful naloxone distribution program for officials to realize that they needed something similar to SBIRT. In late November, three hospitals in the Barnabas Health system agreed to participate in a pilot program in which trained screeners will visit overdose survivors in the emergency room and encourage them to seek treatment. Right now, the options are methadone clinic or a detox facility, but either of them could be a springboard to further help.

Officials and health care workers want to see that program expanded to other hospitals in Ocean County, and a broader range of care. “That will be the closure of this—getting those patients dealt with and expanding the program to other people needing opiate dependency treatment,” said Raj Juneja, a doctor who runs a private treatment center and member of the Ocean County Opiate Task Force. The group was formed in August 2013 in response to the opiate crisis and advocates for a more integrated approach to addiction. “It’s all about access. We need to get them access.”

But that is a long way off. One person was referred to treatment—to a methadone program—through the pilot's first three weeks. Officials acknowledge that change can be slow. “Just like naloxone, which took us until spring of this year, these things are new,” said Al Della Fave, Coronato’s spokesman. “It takes convincing people that this is not the easy road, but it’s one we’re choosing to go down.”