As athletes from around the globe arrived in Rio last week to compete for Olympic gold, Brazil’s notorious hacker underground was lurking just out of sight, competing to rip off as many of the hundreds of thousands of sports fans as possible during the games.

Tourists flocking to Rio are descending into what security experts describe as one of the most potent cybercrime hotspots in the world, where a new generation of young hackers is perfecting and unleashing a spectrum of online attacks in and outside of the country.

Brazil is now second only to Russia as home to the world’s most sophisticated and innovative financial fraud gangs, according to the international software security group Kaspersky Labs, and ranked number one in the first quarter of 2016. Brazilian cyber gangs that once purchased the most cutting-edge hacking tools from Eastern Europe are now increasingly building their own.

“It’s the equivalent of an industrial revolution in Brazil with respect to cyber capabilities,” said Tom Kellermann of the data security firm Strategic Cyber Ventures, who recently completed a major study of cybercrime in Latin America.

The Brazilians are especially proficient in online attacks on bank accounts and cloning of U.S. credit cards, which were an attractive target because until recently most did not contain the vital security “chip.” In a warning issued earlier this year, the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security called financial cybercrime in Brazil an “epidemic.”

Brazilian banks lost more than $550 million U.S. dollars to internet fraud in 2015, according to the Brazilian Federation of Banks.

NBC News made numerous unsuccessful attempts to contact a dozen individuals identified by Latin American security analysts as known Brazilian hackers. During this time, an NBC News reporter’s personal bank account was hacked and more than $1000 was stolen.

Despite enormous efforts on the part of the Brazilian government and Olympic organizers, cyber security experts have been warning for months about the possibility of a blitz of internet fraud.

Fresh data collected by the security firm Fortinet from more than 2 million sensors worldwide detected the creation of at least 3,800 bogus malicious website URLs containing the Brazilian government designation “gov.br” between April and June, the firm said last week.

That’s an 83 percent spike in newly created “phishing” malware aimed at Brazil, compared with an average 16 percent increase in such malware worldwide. Malicious URLs masquerade as legitimate web addresses to steal online customers’ private information.

“You Lose, Playboy”

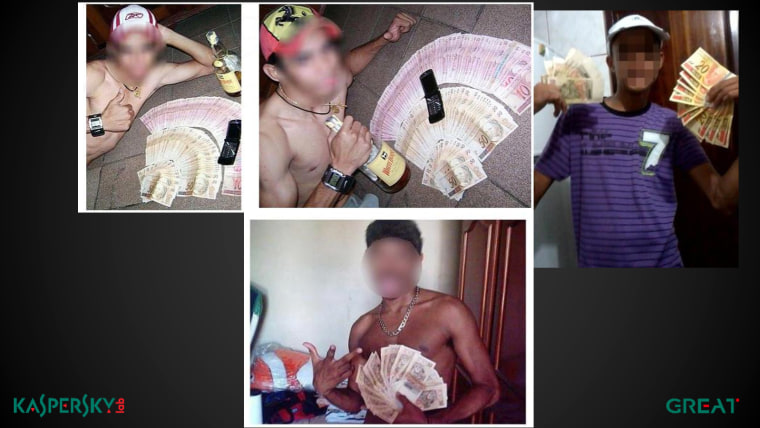

What’s unique about Brazil’s underground is how openly its gangs flaunt their crimes because, experts say, the country’s lax cybercrime laws generally protect hackers from serious consequences.

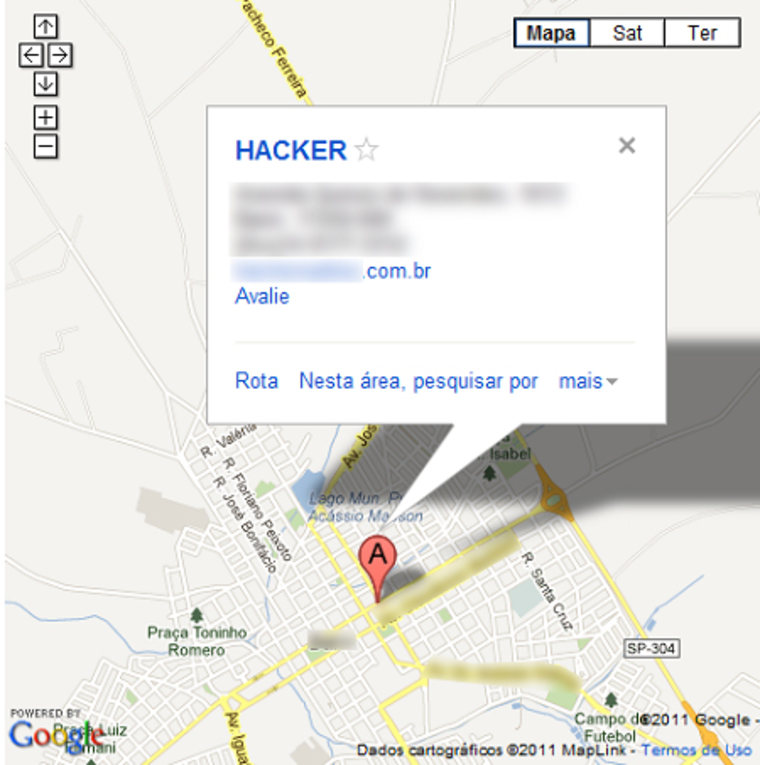

Throughout the slums or “favelas” that surround big cities like Rio and Sao Paulo, teenage hackers parade their riches in the streets, brag on social media platforms, write Robin Hood rap songs about their exploits, and spend their proceeds on prostitutes. There are even brick-and-mortar hacker schools that advertise their addresses and pinpoint the locations on Google Maps.

Security analysts said that Brazilian cyber-gangs, which use street names like PrimeSuspectz, CodeCash and Silver Lords, have developed a well-earned reputation for audacity. In a 2015 Kaspersky Labs report, senior security researcher Fabio Assolini cited two examples of hackers bragging about their exploits in videos posted to YouTube.

In one video that’s garnered more than 250,000 YouTube views since 2013, the thieves rap, “I’m a virtual terrorist, a criminal; on the internet I spread terror, have nervous fingers; I’ll invade your PC, so heads up; you lose, ‘playboy’, now your passwords are mine”.

In another popular video, hackers chant: “You work or you steal, we cloned the cards…I’m a professional fraudster and cloner, we steal from the rich, like Robin Hood.”

Cybercrime only became a criminal offense in Brazil with the 2013 passage of the Carolina Dieckmann Law, named for a Brazilian actress whose nude pictures were hacked and posted online. That law carries only modest penalties of fines and up to a year in jail.

“The police do their job, they make the arrests,” said Assolini, who last fall published a five-year study on cybercrime in Brazil

“But the law is so soft that it’s very rare for a bad guy to go to jail. They have money so they are able to hire very good lawyers to defend them. The bad guy lands in jail [in Brazil] sometimes, but only after doing a lot of bad, bad things.”

Kellermann told NBC News that Brazil’s best cybercriminals have become so skilled so fast in the past couple of years that they’ve drawn the attention of Latin America’s feared drug lords.

“The Brazilian underground, unlike the Russian or German undergrounds, are only partially submerged [into the ‘dark web’ online],” said Kellermann.

“Much of it is on the surface web,” he said. “The Brazilians are more brazen -- and now there’s evidence that they are endowing or selling their capabilities to major narco-trafficantes in the region, as well as being forced to do so.”

While the majority of online fraud committed by these gangs has been aimed at Brazil’s banks and citizens, about seven years ago they turned their attention to financial fraud in the United States, Kellerman said.

“Chupacabras”

Researchers from Kaspersky Labs and other security firms directed NBC News to Brazilian hacker social media profiles and how-to websites like Hacker Xadrez (“Hacker Chess”), where anyone with a few hundred dollars can buy online tools – known as “exploit kits” –- to hack banks, businesses and individuals, hold data ransom, clone credit cards, steal e-wallets with RF scanners, and install “skimmers.”

The skimmers, which thieves attach to ATM machines to capture customers’ banking data, are known in Brazil as “chupacabras” –- a reference to a mythical Latin American beast called the “goat-sucker.”

One popular Brazilian hacker class that Assolini has identified, which has been around since at least 2012, costs about $75 and promises each graduate a bonus of 60 million stolen email addresses to exploit.

“Nowadays the virtual world is increasingly competitive, making it harder for new users to compete with advanced rivals in an ever-growing marketplace,” a course description reads. “That inspired us to create the Kit Spam, where we include 60 million email addresses divided into separate categories: professionals, individuals and companies, executives, businessmen, politicians.”

NBC News reviewed several of the Portuguese language Hacker Chess online courses.

Lax Laws Insulate Many Brazilian Hackers

Brazilian authorities have been cracking down on cybercrime for months in anticipation of the Rio Olympics, Assolini said.

In June, the Brazilian Army’s Center for Cyber Defense (CDCiber) announced that it had recruited 200 security experts to combat hackers and cybercrime. A spokesperson for the Brazilian government did not respond to requests for comment.

While Brazil’s military is responsible for national cyber security, the security firm Atos safeguards the Olympic systems themselves.

Atos “has provided secure, reliable IT systems for the Olympic Games since we began working with them in 1989,” a spokesman for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) said, adding that the IOC is “confident in the measures [the Brazilian government has] put in place.”

Some analysts fear that with limited resources, Brazilian authorities have been more fixated on cyber terrorism than cybercrime.

“Instead of focusing on international and domestic cyber-criminality, which constitutes by far the gravest risk, the state is doubling down on strengthening cyber war-fighting and anti-terrorism capabilities,” Dr. Robert Muggah, a security specialist with the Latin American think tank the Igarape Institute, wrote in an analysis published last year.

“This is not to suggest that cyberterrorism and cyber warfare are not real threats. Rather the government is overemphasizing broader issues of national security rather than addressing the most pressing challenges confronting citizens—that is cyber-crime.”

Muggah’s concerns were borne out recently when Assolini and his team spent two days identifying and monitoring about 4,500 Wi-Fi access points near three Olympic locations – the Brazilian Olympics Committee building, Olympic Park and a trio of stadiums.

The analysts reported that about a quarter of the access points appear to be insecure – either because they were transmitting data without encryption, or operating on an easily hackable algorithm.

Brazil’s Booming Internet Culture

Brazil’s emergence as a cybercrime hotspot has been years in the making. Since at least the 1980s, Brazil has been at the forefront of electronic banking, and it was among the first nations to adopt anti-hacking “chips” in credit cards in 2003, Assolini said.

It’s home to the world’s second-largest ATM market, according to one study. More than 96 million people - 55 percent of the population – are online. Cyber-attacks within Brazil jumped 197 percent in 2014 and 274 percent in 2015, according to U.S. and Brazilian security analyses.

As internet access has spread in recent years, Brazilians have embraced the medium like no other Latin American country, but often without the security sophistication needed to protect themselves.

Brazil is second only to the United States in registered Facebook users, and fifth globally in registered Twitter accounts. Nearly half of all banking transactions in Brazil are conducted digitally.

Much of the nation’s internet usage, including banking, occurs on mobile phones and in internet cafes and public libraries, making it harder to detect fraud, experts said.

“More Difficult Than We Ever Imagined”

The challenges facing authorities in Brazil and other countries have been exacerbated by the growing use of end-to-end encryption, anonymous web-hosting and the growth of peer-to-peer online currency like Bitcoin, and what Kellermann described as the inability of most online security to thwart hacker attacks before they proliferate.

“This is more difficult than we ever imagined before because of the infrastructure of the criminal enterprises that use anonymous payments and bulletproof [web] hosts,” he said. “It’s not just Bitcoin being used. They’re using Webmoney, Bitcoin and Litecoin. The fundamental reality is that most cyber security tech is ineffective in stopping the attacks. The average criminal no longer has to be a software engineer to distribute these attacks as they are easily purchased. That’s the harsh reality of cybercrime.”

Brazil’s top cyber-gangs are now pushing past even the Russians in an imminent new epidemic – mobile malware, a type of ransomware which attacks your cell phone, and can freeze the contents until you pay a ransom, Assolini said.

“This is something new in the Brazilian underground. They are offering mobile malware kits. Can you imagine how interesting that will become?” he said, sarcastically.

Brazilian cyber-criminals also have developed a singular reputation for bold revenge measures, including threats to specific researchers.

“They don’t like us,” Assolini said with a laugh. “It’s very common for white hat [researchers] to receive threats and bad words in the code of the malware. I was reading some malware I discovered and [a hacker known as] Codecash –- he sends me messages -- in the code of the malware! They say ‘leave [hackers] alone, they need the work’ and things like that.”

Yet for all of their technical proficiency, some Brazilian cyber criminals may not be rocket scientists.

Following revelations in 2013 from former U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden that the agency spied on Brazil’s president, hackers retaliated by infiltrating what they thought was the NSA’s website, and leaving messages imploring the U.S. to “stop spying on us.”

Apparently due to a typo, they infiltrated the website of NASA, America’s space agency.