The suspect in the New York and New Jersey bombings posted links to radical videos on social media as early as 2010, but his social media posts weren't vetted by authorities when he received U.S. citizenship in 2011, NBC News has learned.

U.S. intelligence sources also believe Ahmad Rahami traveled to Syria in 2013 or 2014, in addition to visiting high-risk terror areas like Quetta, Pakistan, repeatedly.

In fact, Rahami left a trail of clues that raise questions about whether he could and should have been detected by authorities — perhaps the latest example in a recent history of domestic terror plots littered with missed opportunities.

In San Bernardino, Orlando, and Boston, Americans radicalized to violence killed dozens of their fellow citizens — after exhibiting a pattern of behavior beforehand that might have alerted authorities.

Officials say that strict rules governing investigations — essentially, a probe must become a full criminal inquiry or be closed — limit the FBI’s ability to scrutinize troubling behavior that isn’t criminal. And the U.S. intelligence community, despite post-9/11 reorganizations that assigned domestic terrorism analysis to the National Counterterrorism Center, has repeatedly failed to tie together foreign travel and social media activity with domestic law enforcement probes.

Some constraints are driven by basic constitutional principles restricting police power and government surveillance. Counterterrorism officers within the New York Police Department (NYPD) told NBC News that some of the problem stems from a fear of being seen as “profiling” Muslim communities. Others said it is as simple as the FBI not sharing information with the resource-rich local authorities.

"Our thinking and practices regarding domestic threats needs to radically change in this ISIS era," a senior U.S. intelligence official told NBC News.

Click Here to Read an Earlier Version of This Story

Below is a list of occasions when Rahami came to the notice of government officials — and, in some cases, of potential clues that weren't pursued.

- As a youth, Ahmad Rahami had traveled to Pakistan, and perhaps Afghanistan, as early as 2005.

- Rahami became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 2011. NBC News has learned that U.S. officials didn't check his social media accounts at that time. An Obama administration official acknowledged that the Department of Homeland Security was not checking social media at that time, and only recently began a pilot program to do so.

- If they had checked his accounts, U.S. intelligence officials told NBC News, they would have found multiple links to radical jihadi videos.

- Rahami and other members of his family brought a civil discrimination suit in federal district court in 2011, alleging they were harassed for being Muslim. The dispute was about noise from the restaurant, which stayed open late, but the Rahami suit quoted the neighbors as saying, "Muslims make too much trouble in this country." The suit references a previous arrest of Rahami's brother Mohammad for assaulting a police officer.

- Rahami visited Quetta, Pakistan, considered a high-risk area by the government, in late 2011, staying six months. He received a "secondary inspection" from U.S. officials on his return. Rahami, an Afghan-born U.S. citizen, said he was attending a wedding and visiting family.

- Rahami married an Afghan national named Asia Bibi while in Quetta, according to two senior U.S. intelligence officials. Before his return to the U.S., he contacted his congressman and asked for assistance bringing his new wife to the U.S. That request was forwarded to the State Department and USCIS, a part of the Department of Homeland Security. Because she held an expired passport and was pregnant, her visa was delayed. She subsequently received a visa to enter the United States after she gave birth to a boy. She was vetted by U.S. intelligence upon granting of a visa and entry to the U.S. in 2014 as a green card holder.

- Back in New Jersey, according to published accounts, an ex-girlfriend with whom he had a child took out a restraining order against Rahami in 2012. He later violated the order.

In 2012, according to a federal criminal complaint filed against him after the Chelsea bombing, Rahami applied for and received a new U.S. passport. There was again no probe of his social media.

Rahami returned to Pakistan in April 2013 and stayed nearly a year. He lived with family in Quetta. During this time, he traveled to Turkey and Afghanistan and U.S. intelligence also believes that he traveled to Syria, attempting to join foreign fighters. His biometrics — iris and fingerprints — would have been taken on entry to Afghanistan, as has been required of all U.S. visitors since the May 2011 U.S. raid that killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan. That information is shared by the U.S., Pakistan and Afghanistan.

While Rahami was in Pakistan, Afghanistan and elsewhere in 2013 and 2014, his siblings were posting pro-jihadi comments on social media. One posted a quote from U.S.-born radical cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, the recruiter and propagandist for al Qaeda in Yemen who was killed by a U.S. air strike in September 2011.

Rahami’s brother, the same one who was arrested for allegedly fighting with a police officer, visited Pakistan during this period. He is now believed to be living in Pakistan.

Upon returning to the U.S. in 2014, Ahmad Rahami was required to go through secondary screening again and interviewed. According to the New York Times, his travel and interview provoked Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to issue a TECS tip-off message to the National Targeting Center, a flag that automatically notifies authorities of any subsequent international and domestic air travel. The TECS system serves as an early warning system for officials who compile watchlists and the FBI.

In August 2014, Rahami was charged in New Jersey with aggravated assault and unlawful possession of a weapon and was released after posting $25,000 bail because of an alleged attack on his brother with a knife. Law enforcement and intelligence sources state that he stabbed his brother Nasim in the leg and hit his mother Najiba. He spent three days in jail. Charges were pursued, a grand jury was convened, but ultimately the victim recanted.

As part of the August 2014 fracas, a neighbor heard Rahami's father call him a terrorist. The neighbor told the local police, the police told the Union County prosecutors, and the prosecutors informed the Newark Joint Terrorism Task Force. When the FBI went to question the father, he said he spoke in anger and did not believe his son was a terrorist, though he was concerned that his son was hanging around with the wrong kind of people, maybe gang members. According to the official FBI statement: "In August 2014, the FBI initiated an assessment of Ahmad Rahami based upon comments made by his father after a domestic dispute that were subsequently reported to authorities. The FBI conducted internal database reviews, interagency checks, and multiple interviews, none of which revealed ties to terrorism."

FBI agents approached Ahmad Rahami as part of the inquiry, but he refused to talk to them.

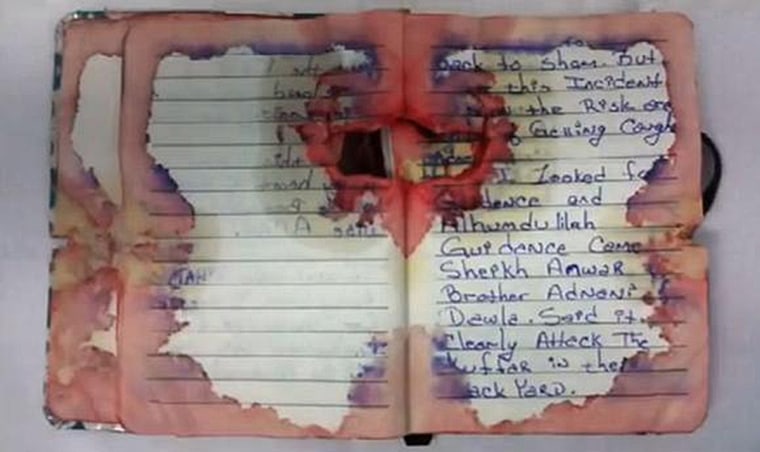

According to a federal criminal complaint filed against him earlier this week, and a senior intelligence official, at the time of the initial FBI probe, Ahmad -- and possibly unnamed accomplices -- had more than one YouTube channel (Yaafghankid786, among others) and designated radicalized videos as “favorites.”

In 2015, according to the complaint, Rahami (and/or accomplices) purchased and evidently activated multiple cellular phones.

Between June and August 2016, Rahami (and/or accomplices) purchased various materials — citric acid, circuit boards, electric igniters, and ball bearings — according to the federal complaint. None of the items purchased were illegal to buy or possess, though it is known that the Department of Homeland Security and eBbay monitor purchases of explosives-related materials.

During the summer or fall of 2016, Rahami (and/or accomplices) prepared at least four different bomb packages — two pressure cooker bombs and two pipe-bomb packages — at some unknown location other than the residence/restaurant. No “see something, say something” reports were made by the public.

During 2016, Rahami traveled to Roanoke, Virginia, and purchased a Glock 19 handgun, federal officials tell NBC News. A senior intelligence official also told NBC News that Rahami obtained a 2014 New Jersey license to own a firearm, though this is still unconfirmed.

On September 15, 2016, Rahami (and/or accomplices) tested a bomb fuse in the backyard of his Elizabeth home, according to the federal complaint. He was filmed on one of the cell phones used in the bomb. According to the complaint, after the fuse is lit, there is “a loud noise and flames,” followed by billowing smoke and laughter. Rahami then enters the frame and is seen picking up the cylindrical container.” No “see something, say something” reports were made by the public about the activity.