The bombs came from the sky and exploded, discharging dark smoke. The smell was terrible — "like rotten eggs" — and the vapor changed to a lighter color.

Some people died right away. Those who survived fell ill almost immediately: vomiting, coughing and struggling to breathe. Over time, many broke out in green or white blisters. Others felt their skin slowly harden, then fall off.

"When the bomb exploded I inhaled the poisonous air, which I am smelling even now," one survivor said — cutting an interview short because he was in too much pain to speak.

His story was one of many contained in a chilling report by Amnesty International accusing the Sudanese government of repeatedly using chemical weapons on civilians in a remote and inaccessible part of Darfur.

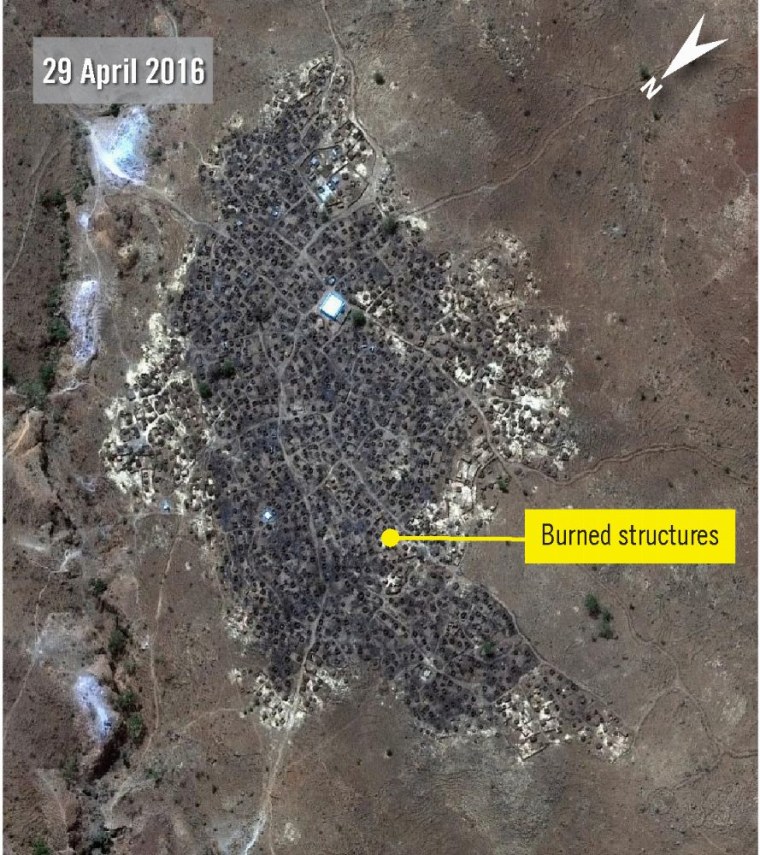

The 103-page report — "Scorched Earth, Poisoned Air" — features satellite images, survivor testimonies and photographs to corroborate what it says are war crimes in Darfur’s remote Jebel Marra region.

According to Amnesty the evidence indicates at least 30 likely chemical attacks have hit the area since the start of the year. The most recent was Sept. 9.

"It’s sheer cruelty — these sorts of weapons are designed to inflict cruelty and they kill," Amnesty's Tirana Hassan told NBC News.

Sudan’s U.N. Ambassador Omer Dahab Fadl Mohamed told NBC News the report was "fabricated," "completely flawed" and an attempt to "tarnish the image" of his country.

"No one from Amnesty International has been to the area to collect evidence," he said, questioning where the images used came from.

"We have to caution against such unfounded accusations which led to the invasion of Iraq," he added. "Categorically with clear conscience we can say that no chemical weapons were used."

NBC News has not independently verified the materials contained in the report.

Jebel Marra is effectively cut off from the outside world — no journalists, humanitarian actors or U.N. peacekeepers have been allowed access since the Sudanese government launched a massive offensive in January to stamp out a long-running rebellion.

"After about two weeks my skin started falling off"

That’s why Amnesty said it had to conduct all of its research for the report remotely — corroborating dozens of interviews with satellite images and consultations with two chemical-weapons experts.

One of the experts said that, when taken together, the eyewitnesses' accounts, photos, and symptom analysis offer enough information to make him "very certain" chemical agents "of some sort" were used.

"The kinds of injuries that we've seen and the explanations for what people saw at the source of the attack could not be explained simply as a result of the explosive effects of either conventional or incendiary munitions," Dr. Keith B. Ward explained.

The experts determined the evidence suggested exposure to a class of chemical weapons known as vesicants — or blister agents — such as sulfur mustard, lewisite or nitrogen mustard. They also said it was possible more than one chemical was in use or that chemical agents had been mixed together.

However, exact identification would require collecting environmental and physiological samples — which Amnesty said is impossible under current circumstances but must be allowed to take place.

*****

Darfur has been racked by warsince 2003, when rebels took up arms against the government in Khartoum.

The U.N. estimates that 300,000 have been killed in Darfur and 2.6 million others displaced. All sides in the conflict have been accused of atrocities: Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir has an outstanding arrest warrant from the Hague for war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.

While the violence has ebbed and flowed, Khartoum has in the past year stepped up attacks on rebel groups. In January, government forces launched a ground and air offensive on Jebel Marra — a stronghold of one rebel Sudan Liberation Army faction central to the conflict that the regime has accused of ambushing military convoys and attacking civilians.

The offensive had displaced as many as 251,000 Jebel Marra residents as of July, according to U.N. figures.

However, U.N. officials have complained that the joint U.N.-African Union peacekeeping mission in Darfur has been denied access to the area to assess the situation.

In the meantime, according to Amnesty, government forces have waged a punishing campaign in the region that has deliberately targeted civilians — not combatants.

The attacks appeared to follow a pattern, the organization said.

Bombs would fall from the sky, then uniformed soldiers would ride into villages on trucks, camels and horses.

"The attacks were also characterized by gross human rights violations including ... killings of men, women and children, the abduction and rape of women," Amnesty said.

It said it had collected the names of 367 civilians — including 95 children — killed by government forces in just the first six months of 2016.

"Most civilians were killed by bombs or were shot while fleeing attacks," the report said.

*****

Amnesty said dozens of Jebel Marra residents — 46 civilians and 10 rebels — alleged in interviews that Sudanese government forces used "poisonous smoke" in attacks this year.

They offered "substantial testimonial and photographic evidence in support of the allegations" that was "broadly consistent," the report stated.

"The evidence strongly suggests that Sudanese government forces repeatedly used chemical weapons during attacks in Jebel Marra," Amnesty stated.

It said it had documented alleged chemical-weapons attacks in and around at least 32 villages in the region this year — with some villages hit multiple times.

A man Amnesty called "Jamous" — from western Jebel Marra — said he’d cared for over 60 people this year with symptoms he thought were due to chemical-weapons exposure.

"There are cases of poison," he explained. "Most of them, they are suffering and then they die."

One was a five-day-old baby boy.

All told, Amnesty said, survivors and eyewitness testimonies suggest that around 200 people — including many children — died from alleged exposure to chemical weapons.

The organization used pseudonyms in the report to protect identities.

"Jamous" and other caretakers described similar symptoms: Vomiting and gastrointestinal distress. Coughing. Eye infections and vision loss. Blisters. Seizures. Urine changing color to dark red or maroon.

"Khalil" — who is in his 30s — told Amnesty a "cloud of smoke" was discharged when a bomb hit his village on Jan. 16.

"It had a nasty smell as if something rotten was mixed with the smell of chlorine," he said.

Khalil told Amnesty of how his muscles contracted and how he vomited. Later that day he said he started "shaking a lot" and losing feeling on his left side; then his urine turned red.

"After about two weeks my skin started falling off," he added.

*****

The use of chemical weapons is prohibited under international humanitarian law — and Sudan’s government is a signatory to the Chemical Weapons Convention that bans their use.

Amnesty said it had sent a summary of its findings to Sudanese government officials, but had not received a response.

In the meantime, the organization is urging the international community to demand that the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons investigate — as the oversight group did following allegations against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

"It is not the case that we can seek accountability for the use of chemical weapons in one place at the expense of another," Hassan explained.

The OPCW said in a statement it was aware of Amnesty's report and would "certainly examine" it, along with "all other available relevant information."

The State Department was looking through the report “carefully,” according to spokesman John Kirby, who called the allegations and images contained within “horrifying.”

“We unequivocally condemn the use of chemical weapons any time and such use against civilians in Sudan if credible would be reprehensible,” he told reporters Thursday.

Amnesty also wants the U.N. Security Council to press Sudan’s government for access to Jebel Marrah — to investigate and also to ensure civilians are actually protected.

The alleged use of chemical weapons represents a "new low" in the cycle of violence, according to Hassan, but also paints the picture of a government that thinks it is "above and beyond the law."

"Darfur has been so cut off for so long that the world stopped looking but the violations didn’t stop happening," Hassan said. "These are amongst the most serious crimes in the world and there needs to be … accountability."