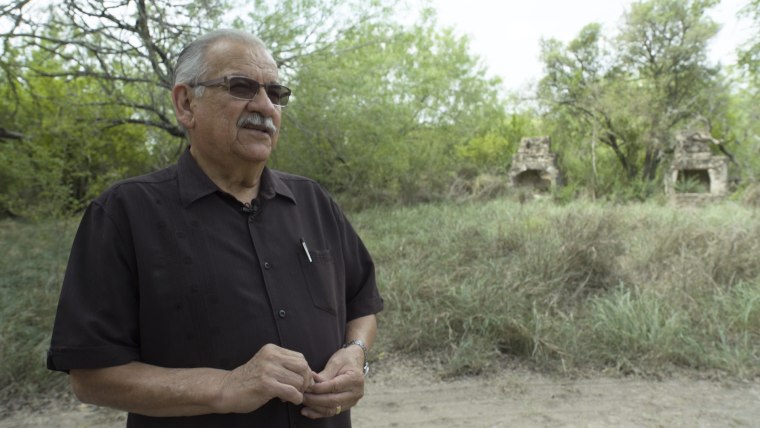

ROMA, Texas — On brushy, cactus-dotted land along the Rio Grande in South Texas are Noel Benavides’ memories of past Easter picnics with his children, nature outings with scouts and links to his family's Spanish and Mexican heritage.

Those connections clash with the future of this land as envisioned by the federal government: a barrier strip bisected by a solid border wall, intended to fulfill a campaign promise to thwart illegal immigration.

In a state where private property ownership is revered, the federal government has laid claim to nearly six acres of Benavides’ ranch, land bestowed by a 1767 Spanish land grant to his wife's ancestors. Now that President Donald Trump is pressing for a border wall, some residents here have been anticipating a vigorous government effort to seize their lands, and the beginning of more alteration of this remote part of Texas.

"The native plants over here are beautiful," said Benavides, whose land was decorated this spring with the vibrant yellow of blooming cactus flowers. "Anytime we get rain here it's going to be beautiful. There's wildflowers, butterflies, wildlife will be moving around ... bobcats, chachalaca, beavers ... The ecology would be really, really impaired if a wall went through here."

"The money for condemnation has already been appropriated. But they come in with ridiculous (valuations). Their real estate people in Dallas don't know anything about this land, neither do the people in Washington," Benavides said.

The condemnation of a parcel of Benavides' property dates to the Bush administration, and has been tied up in court for years as Benavides has challenged the compensation offered by the government. He received a revised offer in February and was told by a U.S. attorney that the wall would be north of an area where a border fence was proposed under legislation signed by Bush.

Benavides sees Trump’s wall as an unnecessary waste of money. He wants to keep his land in its natural state and unencumbered as long as he can, but he said the government's taking of the parcel is “inevitable.” All he can fight for now is a fair price.

“No use in fighting the government,” Benavides said. “You are just delaying something that’s going to happen. Might as well get it over with and go forward.”

This administration hasn't specified whether Benavides' land is destined to host some of Trump's promised border wall, but a draft Department of Homeland Security document dated April 25, 2017 said the administration's priority for a border wall is a 34-mile stretch in the Rio Grande Valley. There were no specifics on where that stretch is located.

Benavides isn’t sure how much of his property he’ll be able to see or set foot on in the future or whether his grandchildren will. With a fence usually comes a road for Border Patrol to have access to the area and that means Border Patrol vehicle traffic through his property. Gates have been erected on some landowners' property where a border fence has been built, allowing them to enter their property behind the fence with an access code.

Other landowners in the area have signed waivers, but most are fighting the government condemnations in court, Benavides said.

“They are not buying all my property, just a strip. So you have 30 acres of 150 acres (of owners’ property) left behind a wall and whose property is that? Is that ours? Is it anybody’s or a no man’s land?” Benavides said.

“Taxing entities value that property. Is it zeroed out and schools don’t get tax revenue from that property? Our kids are going to lose in the long run because there will be no taxes on that property,” he said.

Last month, Trump backed off his demand for a spending bill to include $1 billion for the wall, a demand that almost forced a government shutdown.

But in his 2018 budget request released Tuesday, he asked Congress to provide $2.6 billion for border security, $1.6 billion of which is "actual brick and mortar construction," Mick Mulvaney, Office of Management and Budget director, told reporters in a briefing Monday. Congress doesn't have to follow Trump’s budget plan, but can use the budget proposal as a blueprint.

The cost of a wall that would run the length of the nearly 2,000-mile border with Mexico — as Trump promised in his campaign — has been estimated at nearly $70 billion by Senate Democrats. Trump had said he would make Mexico bear the cost, but Department of Homeland Security Secretary Mike Kelly has also said a wall the full length of the border is unlikely to be built.

A land settled centuries ago

This area of the Rio Grande is rich with the history of America's Spanish and Mexican roots, which often play stepchild to its Pilgrim and other European origins.

Land held by families here was allocated in the 1700s to settlers who had arrived much earlier. The "porciones" or partitions of land here were drawn so landowners had access to the river for irrigation.

Mauricio Vidaurri walks amid his history regularly. His land holds a cemetery where his great-grandfather, grandfather, father and other family are buried. The house where his father was raised still stands on the property.

Vidaurri has not received an eminent domain notice from the government, but he is fearful of what could come.

"When somebody walks in our land for the first time, I believe what they see is history, history that hasn't been seen in a long time. They'll feel, the sacrifice...the pride that we have in taking care of the land. And, they feel a part of something that's very unique," Vidaurri said.

“You have to be standing here, the surroundings, the history, the culture. It takes you back in time,” he said.

The cemetery holds more modern American history too. Vidaurri's father was a Marine who fought at Iwo Jima, was wounded twice and was awarded a Purple Heart. Like his father, Vidaurri also was a Marine.

"Everybody on this land has a cemetery somewhere. And can you picture a wall on top of your relative? In this case, being my father, my grandfather and my great-grandfather. I mean, that's, that's just not right when we have other options," he said.

He points to that service, and his own, to remind Americans calling for the wall that he shares their values, their want for security for the country. But, he said taxpayers' money would be better spent on technology and more manpower, than on a wall.

He said he is concerned how a wall might affect the good relationship area landowners have with the Border Patrol and with "Tick Riders" - the name for U.S. Department of Agriculture inspectors who patrol the river to protect native livestock from fever ticks.

He also fears the loss of his history.

“We just don’t know. We are in limbo,” he said. “I just don’t want to wake up one day and go to my mailbox and get a letter from the Army Corps of Engineers saying they are going to do a survey. Once they do that, that’s the end. They are going to take your land.”

Marshall Crook reported from Roma, Texas, and Suzanne Gamboa reported from Washington.