SAN FRANCISCO — It took traveling more than 7,500 miles away from home for Mia Nakano to figure out what she wanted to do next with her life.

It was 2007, and the Oakland, California-based photographer was interning as a photojournalist for the Kathmandu Post in Nepal. In her spare time, she connected with the Blue Diamond Society, an LGBT rights organization, taking portraits of people who identified as lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, and transgender.

“If we don’t document, we’re invisible … particularly now with today’s current events."

Prior to Nepal, Nakano had just spent five years volunteering at Hyphen, an Asian-American culture magazine. She was the magazine’s first photo editor and also ensured that LGBTQ representation was part of its culture and editorial content.

“That was a really critical turning point for me now that I look back at it — understanding the leverage and power I had as an openly queer media maker,” Nakano told NBC News. “I was doing this thing for five years and totally invested in it. When I left there was a gap. OK, now what do I want to do?”

In Nepal, Nakano realized that her portraits, which she gave to her subjects, held a quiet power, but that “this culture is not mine.” She returned to the United States with the idea for a portrait and oral history project.

“I wanted to … explore the idea of gender, sexuality, and really talk to people about that from a very personal level. And I felt like if I was in the Bay Area and I was kind of struggling and I didn’t feel like I had a solid community and felt alone there, I wanted to understand what was happening in the rest of the country,” she said.

In 2009, Nakano launched the "Visibility Project." She spent the next eight years traveling the country, interviewing participants on camera and taking their portraits. She asked about the ways in which they identified and how that matched up with the way the world perceived and treated them. She never knew if the conversation would lead to an intense revelation about trauma, abuse, or undocumented status, or a celebratory sharing about community and support.

Nakano, 39, has visited 26 cities in 20 states and estimates that she has interviewed more than 200 people. In Kentucky, she spoke with a young Vietnamese trans man who had no resources that were culturally-specific within a 100-mile radius of where he lived. A woman from the Bronx identified not as Asian American, but as gay, queer, or Indo Caribbean.

“In her video interview, she identifies as queer more so in the States. But when she goes back to Jamaica, they don’t use that word. They use gay. It’s also about these shifting identities,” Nakano said.

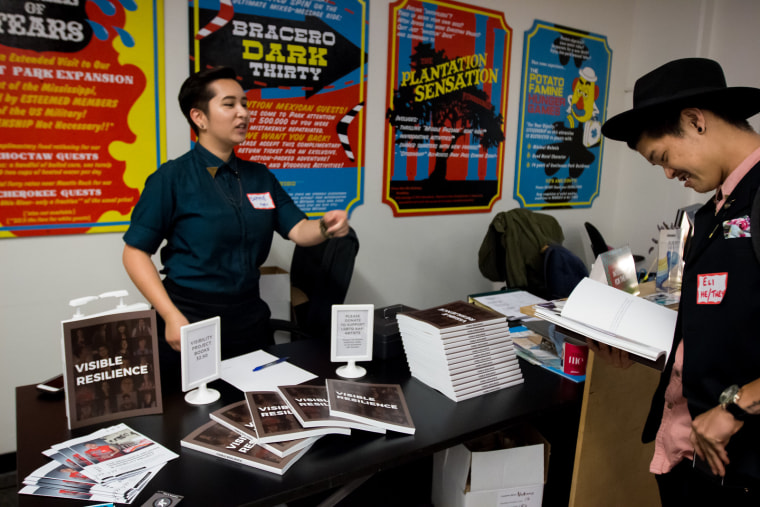

On June 6, Nakano released “Visible Resilience,” a book with 80 of those portraits. The San Francisco launch event, attended by NBC News, included storytelling performances and drew a crowd of more than 200 people of all ages.

Sine Hwang Jensen, 31, the Asian-American and comparative ethnic studies librarian at the University of California, Berkeley’s Ethnic Studies Library said that even at institutional libraries and LGBTQ historical societies, there’s much work to be done.

“So Mia is just such an amazing force for trying to bring these histories to light,” Hwang Jensen told NBC News. “Even these established archives have a lot of catching up to do to the activity that’s been going on for decades in the Asian American community that hasn’t been documented.”

Hwang Jensen consults for Nakano on another project Nakano spearheaded and which also launched the same evening as the book, the "Resilience Archives," a community-based digital history tour map that highlights the contributions, memories, and historical moments of the LGBTQ Asian-American and Pacific Islander community in the San Francisco Bay Area. Resilience Archives collaborators were inspired by the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour but wanted to make the tour digital so those who couldn’t walk or who were deaf like Nakano’s own sister, could access it from anywhere.

The Resilience Archives has also put on workshops; including interviewing and filmmaking; personal archiving, led by Hwang Jensen; storytelling, led by comedian and performer Kat Evasco; and a lecture by artist and longtime queer activist Lenore Chinn.

“If we don’t document, we’re invisible … particularly now with today’s current events,” Chinn, 68, told NBC News. “It’s certainty still relevant when you see anti-gay violence escalate and the violence that has escalated in a number of communities."

"In the Bay Area, we tend to think we live in a bubble — and compared to other parts of the country — that’s certainly still true," she added. "But we’re not immune. It helps to mobilize the psyche in our community and it impacts on a global scale because there are those who live in other areas who don’t have the benefit of a network that they can access physically.”

"I think feeling invisible and isolated — it can really wear down your sense of power. ... And so, just seeing a visual representation of strength where the person is staring back at you ... It was very powerful for me.”

That was true for Hwang Jensen, who grew up in Baltimore, a city she describes as rich in history, but very much black and white, where a queer, multiracial Asian American like herself didn’t feel represented. She heard about the Visibility Project when she still lived in Baltimore and said it made waves on a national level.

“Just looking at the portraits, I remember being so stunned by the strength and just the existence, first of all, on a very basic level, of these visible and out and queer Asian Americans,” Hwang Jensen said.

“I remember being really struck by how strong and how powerful the people in those photos were," she added. "I think feeling invisible and isolated — it can really wear down your sense of power. You feel small; you feel quiet, unheard, silent in a lot of ways. And so, just seeing a visual representation of strength where the person is staring back at you — they’re not looking to the side — they’re looking right directly at you and saying, ‘I’m out and I’m here.’ It was very powerful for me.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.

CORRECTION (June 28, 2017, 5:15 p.m.): An earlier version of a photo caption in this article misstated Sunshine Roc's role in the "Visibility Project." She performed at the project's launch event but was not photographed for a portrait.