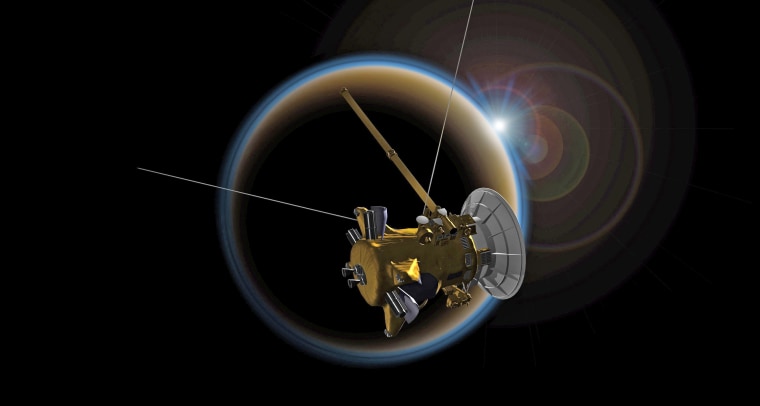

Thick in the night of Oct. 15, 1997, a Titan rocket shattered the darkness over Cape Canaveral and catapulted the six-ton Cassini spacecraft toward a historic rendezvous with Saturn. This week the script will repeat, but with a dramatic flip. Under a noontime sun on Saturn — at 7:55 a.m. EDT on Friday — Cassini will plunge into the ringed planet's atmosphere, briefly blazing once again before descending forever into the black.

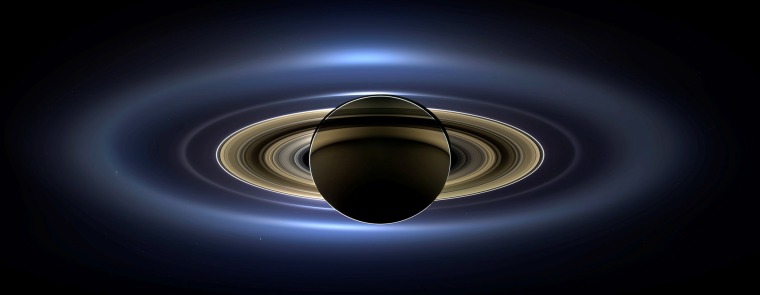

That celestial swan dive will mark the end of one of the most audacious acts of exploration our species has ever undertaken. (You can watch it unfold live on NASA TV in the window below.) Over 13 years, Cassini has scrutinized Saturn and its moons and rings in unprecedented detail — and returned a staggering 453,048 pictures. The results have shifted our understanding of the solar system and redirected the search for life in the universe.

Though Cassini’s demise was planned years in advance, it’s still agonizing to the scientists who have nurtured and even loved the probe since it was first conceived in the mid-1980s.

“There will be an empty place in my heart when I realize that there’s no more direct, personal connection to the Saturn system,” says Linda Spilker, Cassini’s project scientist. “Goodbye, Cassini, and thanks for all the incredible data.”

Bold New Worlds

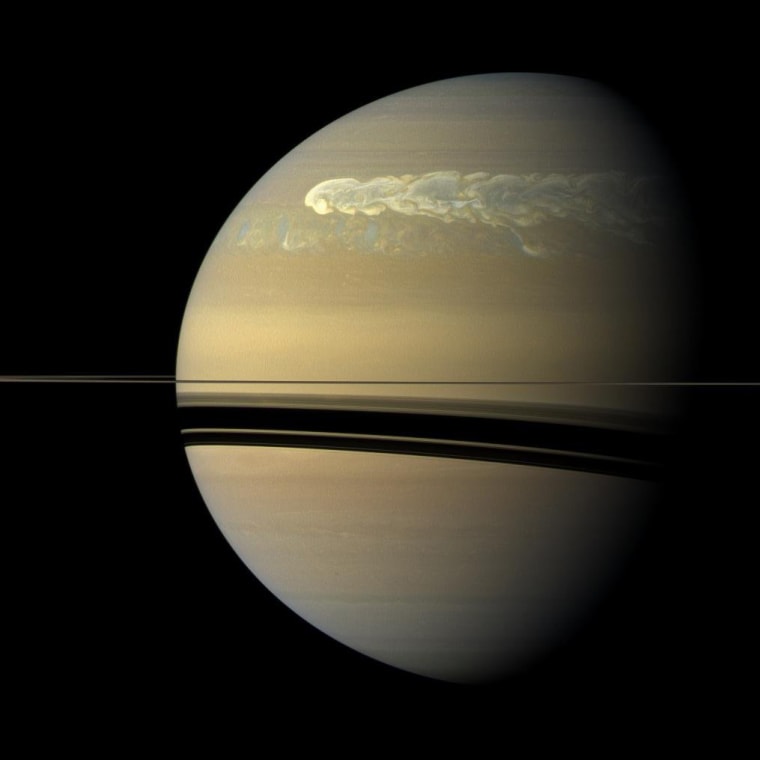

Cassini’s trove of data has yielded some big surprises: Saturn’s atmosphere changes color with the seasons, for example, while gale-force winds shape polar clouds into a puzzling 20,000-mile-wide hexagon.

The planet’s rings pulse with activity, too, as ring particles clump, pile up, shatter and ripple in the gravitational wake of passing moons. This elaborate dance parallels the process that formed Earth and the other planets within a much larger disk around the sun some 4.5 billion years ago.

From Cassini, we know that Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, is dotted with lakes and seas filled not with water but with methane and other simple hydrocarbons. The surrounding landscape, meanwhile, is chockablock with complex organic molecules. Titan may resemble early Earth in deep freeze, a place where we can return to understand how life began.

Even more exciting is Enceladus, an ice-covered moon that may harbor life right now. Cassini’s sensors discovered a network of geysers erupting from fissures near Enceladus’s south pole. The geysers emerge from a warm global ocean that’s believed to be sloshing about no more than a few miles beneath the frozen surface.

Chemical traces in the water show that the ocean is energized by volcanic activity and laced with carbon compounds, two key conditions for biology. Astrobiologists now question whether life really needs a host planet just like Earth, with a thick atmosphere and liquid water up top. Ice worlds that hold their oceans on the inside — like Enceladus — might be just as hospitable, and a lot more common. Enceladus is the key to finding out.

A Life Sacrifice

Ironically, it was the prospect of life on Enceladus that helped determine Cassini’s fate. Early on, mission scientists had considered parking the probe in orbit around Saturn. Over the long term, though, such an orbit could become unstable and lead to a crash landing on one of Saturn’s moons.

Even a small chance that Earthly microbes clinging to Cassini might end up contaminating Enceladus was an unacceptable violation of NASA’s planetary protection protocols. And so, in a 2014 meeting, Spilker and her colleagues resolved to send Cassini to a fiery grave.

They held out as long as possible. Cassini has consumed 6,504 pounds of its original 6,565 pounds of propellant and is now running on fumes, says Earl Maize, Cassini’s program manager. There was just enough left for the probe to set a collision course.

When Cassini enters Saturn’s atmosphere on the 15th, its sputtering thrusters will fire hard to keep its antenna pointed toward home. Eventually, though, buffeting from Saturn’s winds will win out, and the radio link will be broken. Moments later, Cassini’s instruments will be torn off, and what’s left of the probe will vaporize as a bright meteor streaking through Saturn’s skies.

The messages sent back by Cassini just before its demise will contain details about the precise structure and composition of Saturn’s upper atmosphere. That, in turn, will provide clues about how the planet formed and evolved: science to the very end. There will be no final photos, alas. There’s simply not enough bandwidth during the hectic plunge, Maize says.

Strictly speaking, the last communications from Cassini will be ghost signals. Radio waves take 83 minutes to travel from Saturn to Earth. By the time they arrive, the probe will be long gone.

In Memoriam

Maize, like Spilker, is struggling to make peace with that impending loss. “I’m going to feel a little alone,” he says. “But then I think, ‘We’re going out in a blaze of glory. We used up everything in our system, and we nailed it.’”

He expects mission scientists to mark the end of the mission with sober hugs and handshakes — literally, since alcohol is prohibited at government facilities. The drinks and tears will flow that night, when team members plan to go out for a scientific wake.

Not that the probe will truly be gone. It has left behind 635 gigabytes of images and sensor readings — enough to keep planetary scientists busy for decades. Its remarkable discoveries have already inspired concepts for follow-up missions to Enceladus and Titan, as well as a Cassini-inspired mission to Uranus.

The profound sense of interplanetary connection is still there, too, albeit transfigured. One of the Cassini’s discoveries is that Saturn’s interior circulates nearly from top to bottom. That means the probe’s remains will eventually get stirred through the entire planet.

Carl Sagan said that “we are made of star-stuff.” But now we can say, with equal truth, that we are all Saturnians — that we are a part of Saturn, and Saturn is a part of us.