What started as a trickle of individual stories and an anonymous spreadsheet shared among women in media has become a full-scale purge of male journalists accused of harassment and abuse by their female colleagues. The rumors have toppled men who were formerly untouchable and shown a cruel light on the rules for survival within the male-dominated media, even as reports of sexual harassment and assault continue to emerge from Hollywood.

The purge of alleged serial harassers is a good start, regardless of the industry. But at this point, we have to ask whether even firing every sexual harasser in the professional world would be enough to fix a broken system.

It began in the wake of the growing list of allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, when a privately shared spreadsheet of “Shitty Media Men” made the rounds, eventually listing over 70 men in the industry who had been accused of varying degrees of sexual assault, harassment, and all-around crappy behavior toward female colleagues; it was deleted after its existence was revealed to a more broad audience by BuzzFeed. Accusations have continued to crop up since, against both men who made the list and those who did not.

Some were relatively low-level, like freelance writer Sam Kriss, who allegedly forced a woman to kiss him and badgered her for sex until she threw him off a moving bus (he apologized in a now-deleted post after the allegations went viral), or Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi, who has been haunted for years by an allegedly “satirical” non-fiction book he wrote with The eXile co-founder Mark Ames which claims that Taibbi was “always trying to force [female co-workers] under the table to give him blow jobs”. (In a long Facebook post, Taibbi said the stories were fiction, denied any harassment and apologized for his "bad judgment and insensitivity in those years.") Vox Media editorial director Lockhart Steel was fired as a result of sexual harassment allegations made public by a former employee in the wake of the list; The New Republic’s publisher, Hamilton Fish — who was previously publisher of The Nation — is on a leave of absence from the magazine as it investigates allegations of harassment made by current employees after appearing on the list. (Asked for comment, Fish told Deadline “Classic take down underway. We’ll see.”)

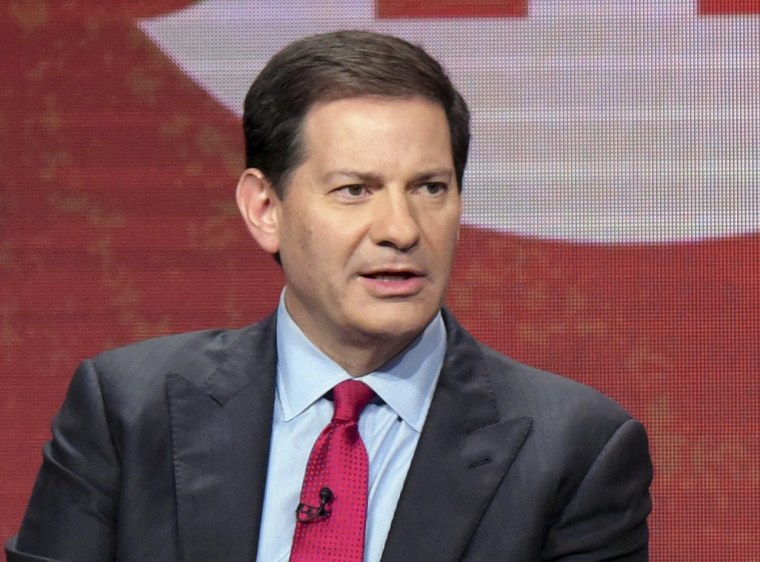

Others were God-tier: Game Change author and senior MSNBC political analyst Mark Halperin has been accused of, among other things, rubbing his erection on female colleagues. He denied the specific claims but issued an apology for actions that he termed “aggressive and crude”; NBC and Showtime both cancelled his contracts. Leon Wieseltier, the legendary editor of The New Republic, was accused of forcibly kissing female subordinates and continually requesting that they “wear something tight” to work; funding was pulled from his forthcoming magazine as a result of the allegations. (He offered an apology for “offenses against some of my colleagues in the past.”) Michael Oreskes, NPR's senior vice president of news and editorial director, was placed on leave and then resigned after the Washington Post published allegations that he abruptly kissed two young female employees during work conversations during to his tenure at the New York Times; NPR reported that another woman filed a harassment complaint against Oreskes in 2015 after he steered a work conversation into sexual territory. (In an internal statement obtained by CNN, Oreskes wrote: "I am deeply sorry to the people I hurt. My behavior was wrong and inexcusable, and I accept full responsibility.)

Men like Weinstein, Halperin or Wieseltier weren’t just powerful; they were central figures of their respective industries, men who set the standards for their peers and heavily influenced the cultural zeitgeist. Weinstein was responsible for much of the ‘90s independent-film boom and made the careers of countless directors and stars; Halperin was considered the definitive voice of a series of campaigns in which women pushed against the glass ceiling; Wieseltier was considered an “aesthetic and moral arbiter” who “shaped the worldview of generations of journalists.”

The trajectory in media of late — trickles that become tsunamis, the unthinkable downfall of untouchable men — mirrors the downfall of producer Weinstein, whose unmasking in the press led to a broad sharing of allegations about sexual harassment in Hollywood that have implicated everyone from Ben Affleck (who apologized for acting "inappropriately" toward actor Hilarie Burton during an appearance on MTV's Total Request Live several years ago) to director James Toback to Amazon Studios head Roy Price. Weinstein’s career is almost certainly over; Price resigned in disgrace.

Seeing men face actual consequences for their alleged actions is a start. But it still may not be enough to keep the problem from repeating itself.

Obviously, firing these men is a good thing: in many cases, the allegations are about continuing behavior and the safety of women in the workplace needs to be secured. Still, having now removed alleged abusers from positions of power, we can start to wrestle with the complex and long-range questions about power dynamics in the workplace.

The existence of so many reports of harassment, coming from this many women in more professions than one can count, suggests that the problem is less a handful of bad men than a broken system. Sexual harassment is usually a symptom of systemic rot: It’s not just about a few abusers managing to get hired, but a culture that is more likely to hire and retain abusive men at the expense of qualified and productive women. The data we have suggests that women are most vulnerable either in conditions of low accountability (like food service and other front-facing service gigs, in which customers can harass female workers with impunity) or in heavily male-dominated industries (like tech or other STEM fields, in which “soft” skills like playing well with others are devalued, and willingness to dominate or humiliate others is seen as a leadership quality).

Harassers have an incentive to hire and promote those who seem willing to give a pass to their behavior. In the best-case scenario, that might entail people who can convincingly grin and bear it; more often, it may well mean men who don’t have a problem overlooking harassment or who are likely to join in. Journalism and Hollywood are both highly competitive industries, in which connections and reputation are incredibly important, and a certain amount of viciousness is necessary for the job. That makes it a perfect petri dish for potential harassment: Young, female targets will worry too much about disrupting their relationships to speak up, and men’s cruelty to targets can be written off as professional ruthlessness rather than retaliation.

This partly manifests in the media’s tendency to protect its own, and specifically men’s willingness to protect other men. Oreskes, who was over 40 at the time he reportedly lavished unwanted attention on a much-younger and non-receptive female colleague in the paper's Washington bureau, faced few consequences though his colleagues were aware of his behavior: in that case, according to the Washington Post, "Eventually, another editor passed the word to a senior editor in New York, who gave Oreskes 'a father-son talking-to,' as one editor put it, warning him to steer clear of the young woman."

But the problem is not as simple as men giving each other cover; the problem is also about the qualities women have had to cultivate — or the rules we’ve had to internalize — in order to survive in environments like these. For Wieseltier, for instance, former editor Michelle Cottle wrote, “women fell on a spectrum ranging from Humorless Prig to Game Girl, based on how much of his sexual banter, innuendo, and advances she would put up with. Once he figured out where to place you, all else flowed from there.”

That’s not an uncommon approach — and it’s no surprise that being the Game Girl will get you places that the Humorless Prig never gets to see. To ensure their own professional viability, countless women have had to fake, or cultivate, Gameness which, in turn, makes it that much harder to fight systemic misogyny, given that their economic security is bound up in their ability to earn and keep the approval of sexist men.

Systems this profoundly broken have a way of making us all complicit. An industry comprised of Bad Boys and Game Girls has no way to eliminate sexual harassment; all of the players are compromised and hamstrung, with half of them refusing to see the problem, and the other half unable to speak. Firing individual harassers when they’re caught is a necessary crisis intervention. But without some profound shifts in the culture, the harassment will be self-perpetuating, and crises will just keep coming.

We have to learn to value women who make themselves difficult when necessary. We have to stop rewarding men for turning a blind eye to other men’s sins. Until we do that, we’ll just be lopping heads off a self-regenerating Hydra of abuse. You can end an individual abuser’s career these days, and sometimes you have to. But we won’t see the end of the problem until we’ve changed the world.

Sady Doyle is the author of "Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock and Fear... and Why'" (Melville House, 2016). She founded the feminist blog Tiger Beatdown, and her work has appeared regularly in Elle, The Guardian, and In These Times, among others. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.