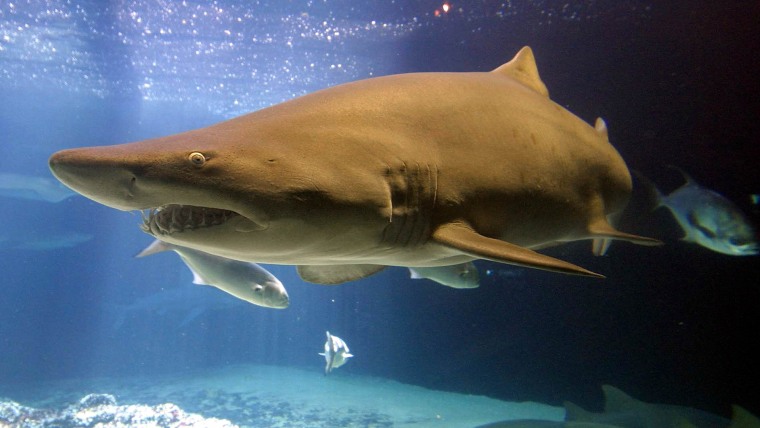

Shark season has begun, thanks to real-life dramas like this month's run-in with a great white shark off the California coast, the buildup to TV extravaganzas like "Sharknado 2" and Shark Week, even the 40th anniversary of "Jaws."

Reports show that shark populations are on the rise, so you can expect to hear a lot about big, bad sharks — but are they really all that bad?

"Having healthy shark populations is critical to having a healthy ocean," Dean Grubbs, a shark researcher at Florida State University's Coastal and Marine Laboratory, told NBC News. "We know they play important roles in the ecosystem."

That's why scientists see it as good news, not bad news, that shark populations are growing in the Atlantic as well as the eastern North Pacific. "It's not just white sharks," said Grubbs, who was one of the authors of the Pacific shark assessment. "A lot of our coastal sharks have seen some level of recovery over the past 15 or 20 years."

NBC News dives in this week with an in-depth look at these predators of the sea. Look for full #Sharkwatch coverage on TODAY, Nightly News and NBCNews.com.

Won't more sharks lead to more shark attacks?

"There's really no evidence to support the idea that more sharks equals more attacks," Grubbs said. Figures from the International Shark Attack File indicate a gradual long-term increase in the number of unprovoked shark attacks, even though the number of sharks has fallen and risen back again.

"The increase in the absolute number of shark attacks ... just tracks the increase in the number of people in the water," Grubbs said. "The rate of interaction, the chance of an attack on an individual swimmer, hasn't changed."

Last year, 10 people worldwide were killed in unprovoked shark attacks, and another 62 were injured, according to the International Shark Attack File. Over the past decade, those numbers have moved up and down. George Burgess, who maintains the database at the Florida Museum of Natural History, says the shifts in the statistics have more to do with "variability in local economic, social, meteorological and oceanographic conditions" for humans than with the rise or fall of shark populations.

Australia has been testing a controversial catch-and-kill program for sharks around the country's western beaches, and the country's Environmental Protection Authority is now considering whether to extend the policy. Hundreds of researchers from around the world have submitted a report saying such measures have no effect on the incidence of shark attacks.

"I think killing sharks is not a good idea. ... Apex predators are really important in ecosystems, and when we kill them what we often find is really bad things happen," Elliott Norse, chief scientist of the Marine Conservation Institute, told Australia's ABC network.

So what works?

The truth is that in many cases, the sharks aren't totally to blame, even for "unprovoked" attacks.

"I would argue that if people are attacked while they're doing things like swimming while they're cleaning fish, or when they're not following the basic rules for swimming in areas where there are sharks, they're increasing their risk of attack," Grubbs said. "Is it really an unprovoked attack when you're wearing shiny jewelry that resembles a fish?"

Leaving the bling on the beach is one of the standard rules for swimming near sharks. Here are a few other tips for when you're in a potential shark zone:

- Don't swim alone. There's safety in numbers, for humans as well as for schools of fish.

- Don't swim at dawn, at dusk or after dark — which is prime time for sharks who are on the hunt. "For a lot of the shark's prey species, that's when their visual system has the biggest problem," Grubbs said. That gives the sharks an advantage.

- Wear black or blue rather than bright colors when you go swimming. Sharks are attracted to contrasting patterns and colors — for instance, the yellow that's commonly used for flotation devices and inflatable rafts. Some shark researchers refer to that shade as "yum yum yellow."

For more tips, check out this list from the International Shark Attack File.

What about that California shark attack?

Burgess doesn't count the July 5 injury of a swimmer at Manhattan Beach as an "unprovoked" attack, because the 7-foot-long great white shark that bit him had been hooked by a fisherman. "In this case, the humans are the villains, not the shark. ... Any animal that's fighting for its life has to be cut a little break in terms of being irritable," he told National Geographic.

The incident illustrates why it's a bad idea to let people go fishing for sharks at a swimming beach. In the wake of the July 5 incident, Manhattan Beach city officials banned fishing from the ocean pier for up to two months.

Chris Lowe, who runs the Shark Lab at California State University at Long Beach, said anglers who fish off public piers should be required to use lines and gear that are designed to break if a shark gets hooked. That means they'd have to put aside the steel cable leaders that are typically used for shark fishing.

"Fishermen and swimmers have increased in number," he told NBC News. "The different part of the equation is the increase in sharks. What we have in America is two generations of people who are not used to sharing the ocean with big fish and mammals. People are going to have to learn to share again. And that means we're going to have to change our behavior."

So who are the bad guys here?

Both sharks and humans are apex predators, so some conflicts are to be expected. The fact is that humans are far deadlier to sharks than sharks are to humans. Conservationists estimate that up to 100 million sharks of all kinds are killed each year, through practices ranging from sport fishing and commercial longline fishing to shark finning for soup.

In contrast, "humans really have very little to worry about" from most sharks, said Greg Cailliet, a professor emeritus at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories in California.

"The ocean is their territory. They live there," he said. "There are only three major species out of 500 species of sharks that are real threats to humans on a regular basis."

White sharks pose the biggest threat in temperate regions, while tiger and bull sharks are the ones to watch out for in tropical regions. The great whites may grab the headlines, but they're responsible for only 36 percent of the attacks recorded since 1580, according to the International Shark Attack File.

Will climate change lead to a continued increase in shark attacks? Burgess suspects that it will — not only because shark species are likely to extend their range in warmer seas, but also because warmer coastal waters are likely to draw more people to the beach for a longer stretch of the year.

"I'd like to think there will be some changes made," he told NBC News. "But the changes will have to be made on the human side rather than the shark side, because they don't have brains as big as we have. The future is in our hands to do the right thing."

#Sharkwatch continues this week across TODAY, Nightly News and NBCNews.com. The Discovery Channel has scheduled its Shark Week lineup of TV documentaries for Aug. 10-17, while "Sharknado 2" is due to air during Sharknado Week, July 26-Aug. 2.