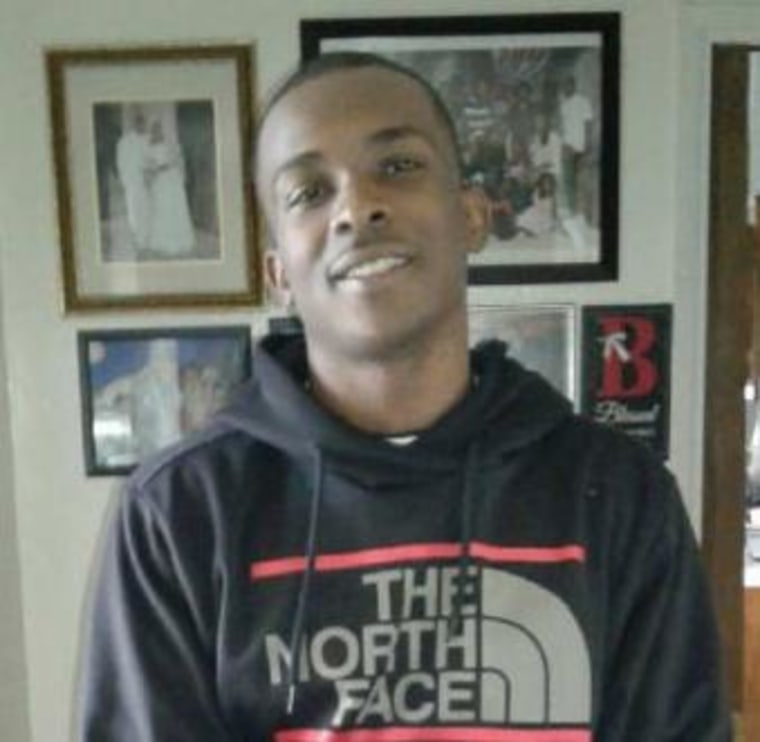

SACRAMENTO — They didn’t know Stephon Clark, but they came anyway Wednesday from all around this capital city, and parts beyond. They came because they said the 22-year-old could have been their brother, or son or grandson and they wanted to try to make sure that the way he died — unarmed and innocent, as far as they could tell — will never happen again.

While Clark’s girlfriend and two young sons watched over his body for hours at BOSS Church on the south side of town, strangers shared a grief they said belongs not only to their city but to all of America.

One day later, a funeral for Clark was held Thursday at Bayside of South Sacramento church. The Rev. Al Sharpton gave the eulogy, saying that it's time to "stop this madness" of black men dying at the hands of police.

On Wednesday, cousin Suzette Clark said the family wants Stephon Clark remembered as an outgoing, funny, handsome, loving father of two young sons — as "more than just a hashtag."

"I just hope it can bring people together," she said of the two-hour funeral set to begin at 11 a.m. "Emotions are heightened, but I just hope everyone comes and shows compassion."

On their way in and out of Wednesday's wake, the mourners raised tough questions: about other tactics the police might have tried, about warnings they said did not come, about another recent deadly police shooting of another unarmed black man in their city and about why some of the country’s mass murderers come away from police encounters better than Clark did.

"I’m so tired, so tired. I just don’t want to see this no more," said Cynthia Brown, who recently retired after 32 years as an executive assistant in the state Franchise Tax Board. Brown said she never knew Clark, but came to the vigil to tell anyone who would listen that things had to change.

She had vented on Facebook the night before and invented a hashtag — #StephonClarkLastOne. "Please let him be the last one," Brown told a reporter. "He has to be the last one."

Joining Brown outside the church not far from the the Gardens neighborhood where Clark died on March 18 were many others who felt the same way and who realized that made them not so different than the teens from Parkland, Florida, who have made it a crusade to make the mass killing at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School a true turning point.

“Everything has an ending. This has to be an ending," said Rahim Wasi, "60-something," who is an employment training instructor for the state of California.

Many of them wondered why the police couldn’t have used a taser, or a beanbag gun, or simply backed off and surrounded the yard where they found him. Didn’t they have a helicopter looking down? Was there truly a danger, if all officers were looking for was a car burglar?

"I mean, you can taze him, or get around him or throw a net on him. Something," said Wasi. "But instead you shoot him. The training is to shoot him. Why not just disable him?

"There has to be a better way," Wasi said.

It wasn’t lost on several of those outside the wake (which media were banned from attending) that the remembrance came the day after authorities in Louisiana declined to prosecute two police officers who shot and killed Alton Sterling, another black man, in 2016.

Sterling, 37, was carrying a loaded .38-caliber pistol in his pocket, but it was disputed whether he was reaching for the gun when the police fired. A video of the episode fueled a nationwide furor about police shootings.

"They had him pinned down," recalled Brown. "How can you not prosecute that? It’s not that we don’t want to trust you, the police. It’s just that you have given us so many reasons and situations not to trust you."

Tiffany Fears, 42, came from Carmichael, north of Sacramento, to support the Clark family. She recalled last month’s massacre at the Florida school and the 2015 episode in Charleston, S.C., in which white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine black congregants at an African-American church.

"In the church and then with this guy who killed all the kids in Florida, how did the guys with the guns walk away from that?" Fears asked. "But here, this one kid hasn’t done anything and he doesn’t walk away. I don’t get that. I just don’t get that."

Clark was killed by officers responding to reports of a man smashing car windows. Police bodycam video shows the officers chase Clark and corner him in a backyard. The officers say in the footage that they believed that Clark was armed; one shouts "Gun! Gun! Gun!" before the officers fired 20 times at him. No weapon was found, only a cellphone.

As the video continues to roll in the aftermath of the shooting, one officer says, "Hey, mute," and the videos' audio goes silent. Police say their investigation into Clark's death will include why the officers muted their cameras.

Police shooting of unarmed black men have been a cause célèbre nationally for years, most famously in Ferguson, Missouri, after the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown. People in Sacramento’s poor, minority neighborhoods recall an even more recent deadly confrontation. In July 2016, police shot and killed a 51-year-old black man with a history of mental disabilities.

Joseph Mann was taken down by 14 bullets, including those fired by an officer who had once been stripped of his weapon because of alcohol and domestic abuse allegations, The Sacramento Bee reported. The two officers involved in the shooting left the police force late last year, though they were not prosecuted.

Cynthia Brown said she strains for what to tell her own grandsons, 23, 15 and 10 years old. Perhaps they should always have their phones in a pouch, never having them in hand, where they might be mistaken for a gun. Or maybe they should throw themselves to the ground, their hands outstretched, any time the police stop them.

"They are perceiving all our young men as one type of person — thuggish, gun-toting, disrespectful," said Brown. "And every black kid is not a thug. They are not gun-toting. A lot of our black children have love, respect and compassion."

She said she had a message for police officers: "Find it in your heart to have some compassion, too. Find it in your heart to learn how to deactivate a situation."

Brown now works as a server for fans at the Golden 1 Center arena. She has seen crowds, and her tips, wither away the last few games, as protestors blocked some fans from entering the Sacramento Kings arena. She says that the protests are worth it to keep her fellow citizens just a bit off kilter.

"If you are uncomfortable, remember that we live uncomfortable every day," Brown said. "I don’t think you are going to see a lot of let up, a lot of back down, in this community. At least until these officers are charged. If they don’t get charged the message will be, ‘We can do what we want to you guys. We can even kill you.’ And that can’t stand."