A Facebook post was what alerted Katelynn Gurbach to a massive tank malfunction at University Hospitals Fertility Center near Cleveland a year ago. A friend tagged her on a news story about the incident. “Oh my God, do you think this is you?” the friend asked.

“I said, ‘no…’” Gurbach, 29, told NBC News, figuring at first that it couldn’t be true.

“Then I lost my mind.”

Gurbach, of Wickliffe, Ohio, lost 10 eggs and four embryos when the liquid nitrogen freezer tank at the center failed the weekend of March 3-4. Those were her only chances of having a biological child. She’d been diagnosed with ovarian cancer at 23, and had stored them at the University Hospitals facility before having her ovaries removed.

Gurbach said all she’d ever wanted was to be a mother. “I was heartbroken. I was devastated,” she said. The memory still brings tears a year later.

“There were a lot of hopes and dreams in those (eggs and embryos),” she said.

The problem had gone undetected for an undetermined period of time because a remote alarm system — which should have alerted employees to temperature swings in the tank — had been turned off. University Hospitals later sent letters to almost 1,000 affected patients apologizing for the malfunction. None of the almost 4,000 eggs or embryos stored at the facility remained viable.

The incident occurred the same weekend that another storage tank failed at the Pacific Fertility Center in San Francisco, also resulting in the loss of eggs and embryos. Despite the eerie timing, the problems were found to be unrelated.

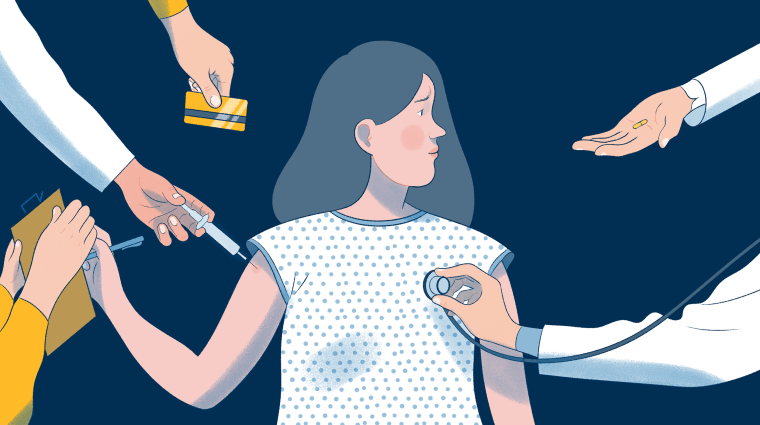

News of the tank failures, which resulted in the loss of eggs and embryos belonging to people who had paid these facilities to safeguard them, horrified fertility doctors and women around the country.

The incidents quickly damaged the reputation of the fertility laboratory industry, which many families depend on to preserve their futures.

In the year since the malfunctions, there have been some changes and improvements. Extra precautions have been established at some facilities, including new inspection safeguards, backup tanks and updated monitoring systems.

But the failures did not stir a move toward greater government regulation to reassure the growing number of women freezing their eggs. In reporting this four-part series on the egg-freezing industry, NBC News has found that there is no single government agency empowered to crack down on mistakes or malfunctions by fertility centers.

The centers are subjected to oversight by a wide range of authorities, from federal and state government agencies to private professional associations and accrediting organizations.

Some agencies and organizations monitor the industry and collect data on it. But the freezing tanks or other devices used for the long-term storage of reproductive materials are not subject to consistent oversight or regulation, and no government agency has stepped in to impose new requirements despite last year’s failures.

WHO’S ON THE HOOK WHEN YOUR EGGS GO BAD?

None of the existing oversight efforts or regulations could prevent last year’s incidents. Both fertility center facilities had passed their most recent inspections and had up-to-date accreditation from the College of American Pathologists at the time.

So who or what regulates the storage tanks that are used to hold people’s reproductive material — the sperm, eggs and embryos, which represent opportunities to conceive children in the future — as well as the alarm systems that monitor them?

NBC News contacted multiple agencies and organizations — including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the College of American Pathologists, and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations — and found the buck stops, well, nowhere.

The ASRM, a nonprofit organization of fertility industry medical and laboratory professionals and scientists, takes the lead in maintaining and distributing standards in the field of reproductive medicine. Its members contribute to the designs of protocols for inspections of fertility centers.

But the ASRM acknowledges there’s no single governmental entity overseeing the fertility industry.

“In the United States, the practice of medicine, including reproductive medicine and assisted reproductive technology, is not regulated by any one governmental agency or authority,” Eleanor Nicoll, the ASRM’s public affairs manager, said in a statement. “Different federal, state and professional bodies occupy various roles.”

Every two years, lab professionals representing the College of American Pathologists and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, two private organizations, use detailed accreditation checklists and questionnaires to conduct regular inspections of the more than 460 fertility centers in the U.S.to determine if the facilities qualify for accreditation. They visit laboratories, review logs, inspect the facilities and check staff credentials.

Meanwhile, several federal agencies — all within the Department of Health and Human Services — have oversight of parts of the industry.

Federal law requires the CDC to collect and report detailed statistics and pregnancy success rates for each fertility center in the U.S.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services does not certify fertility clinics, but it does have some regulatory oversight of fertility centers that are part of hospitals that accept Medicare/Medicaid patients. The agency certified and had oversight of University Hospitals Fertility Center, which was a Medicare/Medicaid provider, but not the Pacific Fertility Center, which was not.

A loophole in the FDA’s oversight illustrates the problem. The agency regulates medical devices, but it does not regulate egg-freezer tanks at fertility centers because they aren’t labeled or marketed as medical devices by their manufacturers.

The FDA has perhaps the biggest role. The agency said it regulates human cells or tissue intended for implantation, transplantation, infusion or transfer into a human recipient. “Generally, an establishment that recovers, processes, stores, labels or packages or distributes human cells or tissues must register with the FDA,” a spokesperson wrote in response to a query.

But no entity regulates storage tanks when they’re used for assisted reproductive technology procedures, including the tanks that failed last year.

A loophole in the FDA’s oversight illustrates the problem. The agency regulates medical devices, but it does not regulate egg-freezer tanks at fertility centers because they aren’t labeled or marketed as medical devices by their manufacturers.

The FDA regulates cryostorage tanks “only when these devices are specifically labeled for use in assisted reproduction technology (ART) procedures.”

Neither of the tanks that failed last year is labeled or marketed by the manufacturers specifically for that use.

An FDA spokesman told NBC News “FDA is not aware of any” that are.

“There is almost no regulation or oversight of any kind that relates directly to the prevention of mistakes like these,” Dov Fox, Professor of Law and director of the Center for Health Law Policy and Bioethics at the University of San Diego, said.

In 1992, then-U.S. Rep. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., introduced legislation that created some requirements for the emerging fertility industry.

The Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act, which became a federal law that year, required the CDC to collect and report data on pregnancy success rates at fertility centers in the U.S.

It also directed the CDC to develop a certification program that states would carry out. The agency did so, publishing requirements in 1999, but to date, no state has adopted it.

But the final language of the section about certification included a requirement that Wyden, who is now a U.S. senator, did not initially propose — prohibiting the nation’s health secretary and the states from regulating “the practice of medicine in assisted reproductive technology programs.”

It’s not clear why the section was added. One former staffer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, speculated that the medical industry might have requested the inclusion of the language.

There is almost no regulation or oversight of any kind that relates directly to the prevention of mistakes like these.

Dov Fox, Professor of Law and director of the Center for Health Law Policy and Bioethics at the University of San Diego

Fox, who is working with the attorneys for the plaintiffs in the lawsuits against both University Hospitals and the Pacific Fertility Center, said that the provision is part of the reason the FDA has played no role in supervising egg-freezing tanks.

“They tie the FDA’s hands,” he said.

An FDA spokesperson said the agency does not regulate the practice of medicine.

“The FDA regulates medical products, and manufacturers’ marketed and labeled ‘intended’ uses of those products,” the spokesperson said in a phone interview. “Clinics may use products for off-label uses if they deem it appropriate for the practice of medicine.”

MALFUNCTIONS NOT REPORTED IN THE U.S.

NBC News searched the track record of the tanks and their manufacturers and discovered other incidents involving malfunctions of liquid nitrogen storage tanks that had similarly caused the loss of patients’ reproductive material.

Media reports and regulatory alerts from other countries showed that Michigan-based Custom Biogenic Systems tanks, the same brand used at University Hospitals Fertility Center, had experienced previous malfunctions in the United Kingdom in 2003 and at the University of Florida’s Women's Health Center in Gainesville in 2005.

The incident with the tank in the U.K. generated a “medical device alert” from its Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, which described a problem involving an automatic filling mechanism by which the appropriate levels of liquid nitrogen are maintained.

The alert warned that a sensor tube regulating the filling process can malfunction.

But there was no warning or alert from the FDA.

The mechanical failure of the Custom Biogenic Systems tank at the University of Florida fertility center occurred in October 2005 but had gone unreported to the general public for almost a year. An Associated Press article in September 2006 reported that the failure occurred “when a faulty sensor on a nitrogen-filled tank apparently failed to alert workers that the temperature had risen to a level that jeopardized the sperm's viability.”

A University of Florida Health official said that after the incident, the facility had switched to a different liquid nitrogen storage technology and had added “multiple additional levels of safeguards to help protect specimens, including a 24/7 centrally monitored temperature system and the ability to move cells to auxiliary storage locations if there is an unacceptable variation in temperature.”

The University of Florida Health official said it had also reported the occurrence to the FDA, “as required.”

Still, there was no warning or alert from the FDA to the general public or to the fertility industry.

It would be very helpful to have full knowledge of why things go wrong.

Amy Sparks, president of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology

After the incident at its fertility center near Cleveland last year, University Hospitals described in a letter to patients a problem with its Custom Biogenic Systems tank similar to those in the previous incidents. Its letter stated that the tank’s automatic filling system had "difficulty" and was "not working."

Again, no warning or alert from the FDA.

Custom Biogenic Systems responded to NBC News queries last year with a series of statements. The company denied that issues with the auto-filling mechanism of its tank at University Hospitals constituted a “malfunction” or an underlying “technical problem,” questioned University Hospitals’ method for filling the tank with liquid nitrogen, and noted that an alarm system was off.

The company also noted that the United Kingdom alert “involved a prior design of the unit which was discontinued in 2003,” and was later withdrawn by regulators. It also claimed that the incident at the University of Florida Health facility “was caused by human error,” contrary to media reporting at the time, which was affirmed by a University of Florida Health spokesperson in an email to NBC News.

Custom Biogenic Systems has not yet replied to an NBC News query for this story.

Amy Sparks, president of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology and director of the University of Iowa Health Care’s In Vitro Fertilization and Reproductive Testing Laboratory, said there was no source of information for fertility center managers or the general public to find out whether storage tanks had technical issues or had been involved in previous “adverse events.”

“There needs to be monitoring,” Sparks said. “I don’t know that [regulation is] the avenue. You could still have the FDA approve the tank and the lab fail to do due diligence in monitoring and filling it.”

“It would be very helpful to have full knowledge of why things go wrong,” she added.

“I feel incredibly sad for these patients,” Sparks said, her voice catching. “Just know that there are a lot of us that are working very hard to improve things.”

The incident at the Pacific Fertility Center in San Francisco involved a storage tank manufactured by Georgia-based Chart Industries Inc.

The center sent patients who lost reproductive material an email more than a month later, telling them that the findings of an investigation indicated that the incident “likely involved a failure of the tank’s vacuum seal.”

According to an amended complaint in a federal lawsuit filed on behalf of the patients, four days after the date of that email, April 23, 2018, “Chart recalled several of its cryopreservation tanks, citing ‘reports of a vacuum leak or failure that could compromise the product.’”

NBC News searched for publicly available alerts about the Chart recall and found none from the FDA or other U.S. agencies, but there were several on government regulatory websites of other countries, including the actual recall document, posted on the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s Food and Drug Authority’s National Center for Medical Devices Reporting.

Although the technical problem described to the Pacific Fertility Center’s patients and in the recall notice seem similar, Chart Industries CEO Jillian Evanko said that “the tank involved in the incident at the Pacific Fertility Center was not part of the recall.”

Two months after the incident at the Pacific Fertility Center, a Chart Industries tank that had been part of that recall allegedly malfunctioned in Canada, according to a public filing by the company with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

According to the filing, that alleged failure has led to “purported class action lawsuits filed in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice against the company and other defendants.”

Chart is also one of the defendants in a class action lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, involving the incident at the Pacific Fertility Center.

In a new public filing with SEC last month, Chart stated that the tank in that incident “has been out of our custody for the past six years” since “it was sold to the Pacific Fertility Center through an independent distributor.”

Pacific Fertility Center is also a defendant in that lawsuit. Pacific Fertility Center did not respond to an NBC News email and phone call.

In its online “Cryopreservation” catalog for the product line that includes the exact model of liquid nitrogen freezer storage tank involved in the incident at Pacific Fertility Center, MVE 808AF-GB, Chart Industries describes a primary intended use as the storage of semen and embryos, but for the agricultural breeding industry.

“The MVE Stock Series,” the catalog description states, “provides the ultimate in security for the breeding industry and are primarily used to store semen and embryos.”

HAS ANYTHING CHANGED?

With no immediate plans for increased oversight or regulation, American consumers — and some embryo laboratory directors who are not privy to internal industry reporting — have been left in the dark about previous adverse incidents and warnings about storage equipment and practices.

Wendy and Rick Penniman filed one of at least 82 lawsuits against University Hospitals over the loss of their three embryos, which they had planned to use to create siblings for their two children.

Wendy Penniman said the disclosures about equipment malfunctions and lab mismanagement made public by the incident, and the subsequent media reports and litigation, have changed her views from a year ago.

After going through the initial stages of grief and sadness, she said, now she is angry.

“After the incident, it was like, ‘Oh, it must have been an accident,’” she said. “There’s a lot more visibility now into culpability.”

“It’s changed my perspective on the fertility industry as a whole, and on University Hospitals,” Wendy Penniman said. “It makes you bitter.”

You have to go into this with the assumption that any structure can fail. We just have to have something in place so that the inevitable failure of the tank will not result in the loss of an embryo.

Dr. Zev Williams

A University Hospitals spokesperson said the hospital system “is limited” in what it can say because of pending litigation, but expresses sorrow in a statement given to NBC News. The statement reads in part, “... we have made significant enhancements at the Fertility Center, provided affected patients with ongoing, free fertility services tailored to their individual clinical needs, and we continue to reinforce a culture that encourages our physicians, nurses and staff to speak up when they see ways to further increase the quality of care we provide to patients.”

Fertility center operators elsewhere have also begun to react to the damage to their reputations.

“Lab directors started thinking, ‘Could this happen here?’” said Barb Collura, president of RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association, a national patient advocacy organization.

Collura said she noticed clinics highlighting safety protocols and backup plans on their websites within days of the breakdowns in California and Ohio.

In the months after last year’s incidents, members of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine worked with the accrediting organizations to update the checklists.

The revised checklists added more specific questions probing how facilities using liquid nitrogen storage tanks measure and monitor levels to make sure they are correct, and whether they have backup systems, including empty-but-prepared “standby” tanks in case the primary tanks fail.

Sparks, of the University of Iowa, said those actions were in direct response to the March 2018 incidents to include more specific questions about monitoring and measuring levels of liquid nitrogen in storage tanks.

“Those are some of the things that the inspectors are now looking for,” she said.

The College of American Pathologists released its revised checklists last August.

Accredited labs had previously been required to have “an emergency procedure to provide backup units with adequate storage capacity” in case the ones in use fail.

But the CAP’s revised checklists added new requirements, including that facilities visually inspect storage tanks, and monitor liquid nitrogen levels continuously, as well as maintain enough additional liquid nitrogen supplies onsite to fill a backup unit.

The new checklists also add a requirement that laboratories show how the alarm system works and how they will respond to alarms. They also have to check the alarm systems at least four times a year, an increase from the previous annual requirement.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine is also developing practice guidelines for the storage of reproductive material at very low temperatures, including in liquid nitrogen tanks, which could prompt other changes in how fertility centers handle and store it.

A senior official with knowledge in the cryostorage industry, speaking on condition of anonymity, told NBC News that industry groups are now working with trade associations to develop new standards for the tanks and their monitoring and maintenance.

“There are a lot of additional potential safeguards that could be in place that I think the industry is moving towards,” the official said.

One center says it has created a new safeguard already. The Columbia University Fertility Center in New York has developed a second, redundant monitoring system in addition to temperature alarms. The new system weighs storage tanks to determine if levels of liquid nitrogen are falling.

“When you have even a little bit of nitrogen left, the temperature is still perfect,” Dr. Zev Williams, director of the center, explained. “It’s only when the nitrogen is essentially completely gone that the temperatures start to rise.”

The laboratory tested the system on unused tanks, recreating various types of malfunctions. The scales, it found, were able to detect problems a month before temperature-based alarms did — before the liquid nitrogen was almost depleted.

“That gives you time to identify the problem, fix it, and there’s no harm caused,” Williams said.

“It’s scary to think that currently (in other labs), the first alarm is when the temperature is not optimal,” he added.

The Columbia University Fertility Center uses storage tanks manufactured by Chart Industries — the same company that made the tank that malfunctioned at the Pacific Fertility Center.

Williams said any tank used in any lab might become compromised. “You have to go into this with the assumption that any structure can fail. We just have to have something in place so that the inevitable failure of the tank will not result in the loss of an embryo,” he said.

PATIENTS SEEK ANSWERS

Deborah Anderson-Bialis, 33, and her husband, Jake, of San Francisco, struggled to start a family and went to three different fertility laboratories. The process was draining — emotionally and financially. Just one in vitro fertilization round can cost an estimated $20,000, and many patients go through more than one round.

“The mindset of people trying to conceive and can’t — it’s really dire,” Jake Anderson-Bialis, 39, said. “Your relationship may be on the ropes. The life that you’re shooting for isn’t unfolding like you had hoped. Money and time feel like they’re flying out the window.”

“You’d imagine there’d be a great resource to lead you through probably the most important decision in your life, which is how you’re going to have a healthy child,” he said. “But what’s out there available to patients — and we suffered from this — is really a diet of information that’s full of inaccuracies.”

The mindset of people trying to conceive and can’t — it’s really dire. Your relationship may be on the ropes. The life that you’re shooting for isn’t unfolding like you had hoped. Money and time feel like they’re flying out the window.

Jake Anderson-Bialis

Both the CDC and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology keep online records of the success rates of laboratories around the country. But the couple found the information wasn’t enough.

To address the problem, the couple started an online platform called FertilityIQ. Its mission is to educate fertility patients — no matter where they are in their process of planning a family. The website relies on verified patient experiences. To date, it has more than 300,000 patient participants, with 26,000 reviews on fertility physicians.

The couple ended up having two children on their own, without the help of IVF. Their son, Lazer, is 2 and their daughter, Yara, just turned 1. But they’d always imagined using three embryos they’d stored at a fertility center back in 2013. The couple has chosen not to identify the laboratory, and has not taken legal action.

Deborah was home, nursing Yara, when an email from one of the centers they’d visited came through at 4 a.m. one day last March.

“Writing to inform you about a very unfortunate incident in the laboratory…” the email began. The couple’s embryos were no longer viable — destroying their hopes of adding to their family.

Deborah says the moment was surreal.

But unlike so many other heartbroken, would-be parents who had lost eggs or embryos, she felt lucky. “Thank God, I am holding this baby,” she recalled saying.

A year later, Katelynn Gurbach, who learned of the malfunction from that Facebook post, has settled her lawsuit with University Hospitals. She still dreams of becoming a mother. But her vision of motherhood has changed. She is reluctant to go through the assisted fertility process again.

“Eventually, I will adopt if that’s what God’s plan is,” she said. “I don’t know, maybe I am called to be a foster mom and will get to bless lots and lots of children.”