Scroll through any travel guide of San Francisco, and Chinatown, one of the oldest and largest Asian neighborhoods in the U.S., is usually listed near the top.

Today, visitors can shop for trinkets, step inside the country’s oldest Chinese temple, stop by the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Company, view the Chinatown Gate and taste a variety of Chinese treats. But the origins of San Francisco’s Chinatown — like other Chinatowns — were rooted in the widespread anti-Chinese racism of the late 1800s.

“The Chinatowns we know today — in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles — are really the consequence of the exclusion laws, which created the conditions, between racism and the law itself, for segregated, isolated Chinatowns,” said John Kuo Wei Tchen, chair of public history and humanities at Rutgers University and co-founder of the Museum of Chinese in America in New York.

The first Chinese to arrive in the U.S. came through New York in the early 1800s as tea and porcelain merchants, Tchen said, but it wasn’t until the California Gold Rush of the mid-1800s that Chinese — mostly from Guangdong Province — started entering the country in large numbers to work as miners. Later, many of them took jobs as laborers in agriculture and in building the first transcontinental railroad.

In 1850, fewer than 1,000 Chinese had arrived in California, Ronald Takaki, an Asian American studies professor at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in “Strangers From a Different Shore,” but by 1870, 63,000 were living in the U.S. While the majority resided in California — where they made up one-quarter of the workforce — Chinese immigrants were also a significant part of the population in other Western states, including 29 percent in Idaho and 10 percent in Montana.

Chinese settlements and businesses developed to meet the needs of this new population across the American West, in large cities such as San Francisco as well as in rural towns such as Locke and Marysville, California; Butte, Montana; and Rock Springs, Wyoming. But as the anti-Chinese movement emerged in the 1870s — which included massacres, riots, evictions and legal restrictions on where Chinese immigrants could live and work — rural Chinatowns were destroyed, forcing many Chinese immigrants into urban areas.

Yong Chen, professor of history at the University of California, Irvine, said that about 200 Chinatowns were burned down or otherwise destroyed by the 1880s.

The anti-Chinese movement also affected urban Chinatowns.

“In San Francisco, for example, there were Chinese settlements and stores scattered throughout the city,” Tchen said. “But as anti-Chinese racism began to increase, these settlements became increasingly segregated and concentrated. It became an enclave.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese laborers from entering the U.S., but because merchants were exempted, Chinatowns became full of shops and restaurants. One reason for the proliferation of Chinese restaurants in the U.S. today, Tchen said, is that they once offered a way for Chinese to legally enter the country and do business.

In addition to commerce, social service organizations were also created, often under the umbrella of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, to assist the community.

“They would try to take care of the Chinese because they felt the city government wasn’t taking care of them,” said K. Scott Wong, professor of history at Williams College.

Chinatowns also served other Asian communities. Yen Le Espiritu, professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, San Diego, said that in the early 1900s, many Filipinos came to the U.S. as itinerant laborers who moved around depending on the crop season. As a result, they didn’t establish their own enclaves — except in places like San Francisco and Stockton, California, and Seattle — and instead relied on Chinese businesses.

The Chinese Exclusion Act also had another, unexpected impact on Chinatowns, said Chen, the Irvine professor. The law helped transform the neighborhoods into tourist destinations.

“The ‘problem’ of Chinese immigration, which was seen as a huge threat to this country, racially, economically, culturally, that threat was contained,” he said. “People felt safe and more comfortable to go to Chinatown as an exotic place to experience the foreign culture and to witness the Orient. Going there satisfied people’s curiosity about exotic cultures in the Orient, but also gave them a sense of cultural and moral superiority.”

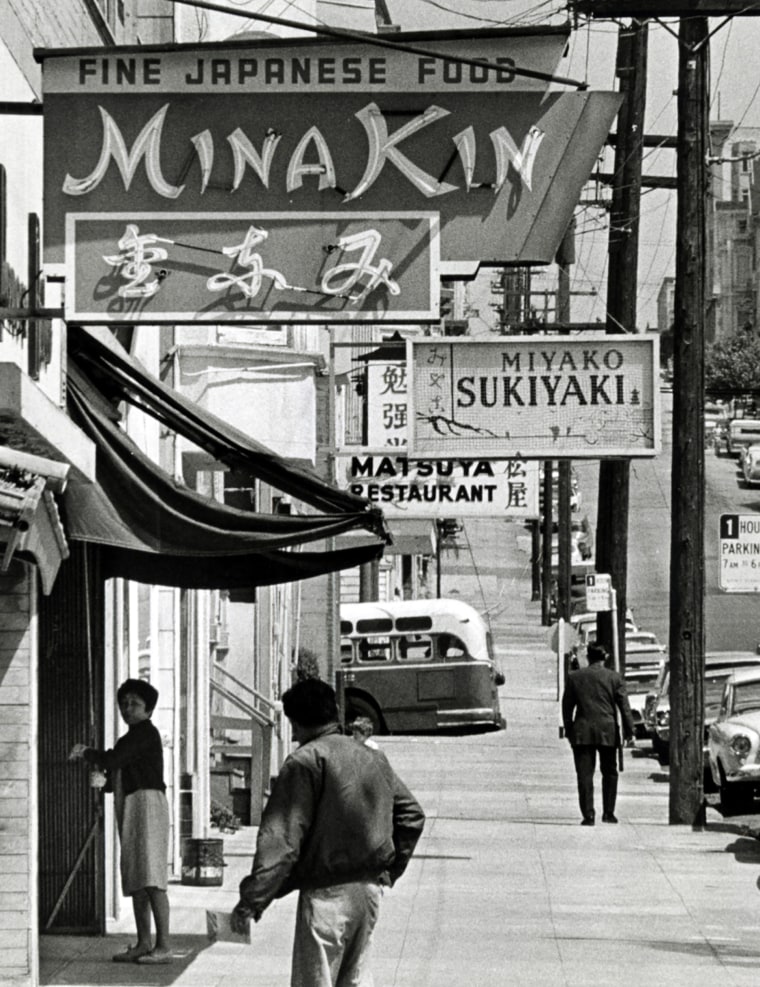

Meanwhile, Japanese enclaves — known as Nihonmachi — also emerged in the American West during this time, due to similar forces of racism and exclusion.

According to “Strangers From a Different Shore,” in 1890, there were only about 2,000 Japanese on the U.S. mainland, but by 1910, they outnumbered Chinese, and by 1930, their numbers nearly doubled to more than 138,000. Urban Japanese businesses also boomed, from 90 to 545 in San Francisco and from 56 to 473 in Los Angeles from 1900 to 1909. And in rural areas, many Japanese field laborers became farmers.

But in 1913, California passed the Alien Land Law, which prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” — including first-generation Japanese as well as other Asian immigrants — from owning or holding long-term leases on land. Later versions of the law were even more restrictive. In 1924, the U.S. passed a law barring the immigration of “aliens ineligible for citizenship” as a way, similar to the Chinese Exclusion Act before it, to halt Japanese immigration.

“It was an economic strategy to keep Japanese Americans from owning, for example, farm land,” said Karen Ishizuka, chief curator of the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. “Not being able to own land really disabled them from providing an economic stability that they otherwise would have had.”

At the same time, Nihonmachis — the most prominent of which were in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland and Seattle — provided critical services to Japanese, said Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, professor emeritus at UCLA. These neighborhoods connected Japanese to jobs and housing, and helped them adapt to a new country.

As a result of exclusion, Nihonmachis — which often developed adjacent to Chinatowns and Little Manilas — also became important social hubs for Japanese immigrants. In addition to traditional Japanese organizations, such as Buddhist temples and judo clubs, larger enclaves also developed institutions parallel to those found in mainstream American society, such as Nisei Boy Scout troops and Christian churches, Hirabayashi said.

“Under such conditions, a unique and specific Japanese American identity began to evolve, and many fascinating transformations occurred,” Hirabayashi said.

But with the forced removal and incarceration of people of Japanese descent during World War II, and later post-war resettlement, which dispersed Japanese Americans throughout the country, Nihonmachis declined or disappeared. Since Japanese couldn’t own property, their rentals were quickly leased to new tenants. In Los Angeles, Ishizuka said, Little Tokyo’s 30,000 residents were replaced by 80,000 new tenants, mostly African Americans from the South, and the neighborhood became known as Bronzeville. By 1950, Hirabayashi said, Little Tokyo was reduced to one-third its former size.

Ishizuka said there were an estimated 40 distinct Japanese American communities before World War II. Today, there are just three — in San Francisco, San Jose and Los Angeles.

Despite the decline of Nihonmachis, Ishizuka said these neighborhoods, in particular Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, continue to be vibrant centers for Japanese American life. So even though most Japanese Americans in Southern California no longer live in Little Tokyo, she said the community increasingly understands that it’s worth saving.

“People realized that it continues to be the cultural as well as historical heart of the community,” she said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.