The dire predictions from 2008 of a permanently ruined relationship between the Clintons and black voters look laughable as the former first lady rolls up crushing majorities over Bernie Sanders among African Americans.

Eight years after losing out to Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton was back, now angling to become his successor. She had, it seemed, repaired all of the damage with Obama from the 2008 primary campaign, with his wing of the party and with black voters in general.

That she had served in one of the Obama administration's most prominent roles, secretary of state, was a big part of this. Her husband’s rousing speech nominating Obama for a second term at the 2012 Democratic convention ("I want a man who's cool on the outside but who burns for America on the inside") had been valuable, too. When Hillary Clinton stepped down from the Cabinet in early 2013, Obama took the unusual step of sitting with her for a joint interview on "60 Minutes." Polls showed her popularity as high as it had ever been with all Americans, and stratospheric with core Democratic groups, including African Americans.

The 2016 Democratic race's formative stage was highly unusual, with one potential candidate after another opting not to run and instead arguing that Clinton should. Thus was the "Ready for Hillary" movement born, and by the time the campaign got underway in 2015, Clinton was facing what looked like an underwhelming group of opponents: Martin O'Malley, Jim Webb, Lincoln Chafee and Bernie Sanders. Initial polls put her national support over 60 percent, with the others in single digits. Joe Biden, Obama’s vice president, toyed with a late entry, but Clinton's poll numbers, her strong establishment support and the conspicuous lack of public encouragement for him by Obama all helped to discourage him from going forward.

It was Sanders who gained traction and became Clinton's main opponent. By the fall of '15, he was running competitively with Clinton in Iowa and New Hampshire, with his national support rising to around 30 percent. Already, though, it was clear he faced a particular challenge if he was going to climb much higher: Black voters were overwhelmingly with Clinton. A poll gave her an 80 percent favorable rating with African Americans. Sanders, meanwhile, was far less known among black voters and had few relationships to draw upon with black leaders. Like Howard Dean a dozen years earlier, his Vermont campaigns had not equipped him for this new challenge.

"Clearly," Sanders acknowledged, "if we are going to do well nationally, it's absolutely imperative that we aggressively reach out and bring the African-American community and the Latino community into our campaign, and that is exactly what we’re working on right now” (“Sanders and the Black Vote," Charles M. Blow, The New York Times, Sept. 14, 2015.)

Sanders hoped his personal history would be an asset with black voters. He'd taken part in demonstrations and run his college campus chapter of CORE — the Congress of Racial Equality — in the early '60s. And he believed his calls for a "political revolution" to fight the power of corporations and the wealthy would have natural appeal across racial lines. It became a familiar refrain from the Sanders camp: Once black voters get to know Sanders, they'll warm up to his candidacy.

The campaign coincided with something of a reassessment among liberal activists and thought leaders of Bill Clinton’s presidency, particularly when it came to his administration’s record on crime and welfare. Pre-emptively, the Clinton camp sought to minimize potential damage.

At the NAACP's July 2015 convention, Bill Clinton brought up the rise of mass incarceration since the enactment of the 1994 crime bill he had championed. "I signed a bill that made the problem worse, and I want to admit it," he said. (“Bill Clinton to NAACP: I wrongly signed laws to imprison nonviolent drug offenders,” Maria Panaritis, Philadelphia Inquirer, July 16, 2015.) More broadly, the former president played a less prominent role on the campaign trail than in '08 and largely — but not entirely — steered clear of the kinds of controversies he'd stoked the last time around.

Hillary Clinton took some heat for her husband's record. Author and activist Michelle Alexander, for instance, argued that critiques of Bill Clinton's policies should apply to Hillary as well, since "she wasn't picking out china while she was first lady" and had been an active proponent — and shaper — of his agenda. Hillary Clinton also apologized for comments that she’d made in 1994 describing "the kinds of kids that are called 'super-predators.' No conscience, no empathy. We can talk about why they ended up that way, but first we have to bring them to heel."

Among black voters, though, the ground never shifted. Clinton continued to run up the score in polling and vastly outpaced Sanders in endorsements. The Congressional Black Caucus's political action committee formally backed Clinton's campaign. Even worse for Sanders, when the PAC announced its decision, Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, a civil rights icon, sounded outright hostile to Sanders and his frequent invocation of his own '60s activism. "I never saw him," Lewis said. "I never met him."

Clinton leaned heavily on her own post-2008 alliance with Obama and criticized Sanders for being insufficiently supportive of America's first black president. Sanders, for instance, expressed support for the idea of a Democratic primary challenge to Obama when he was running for re-election in 2012 and argued that Obama hadn't "bridged the huge gap between Congress and the American people."

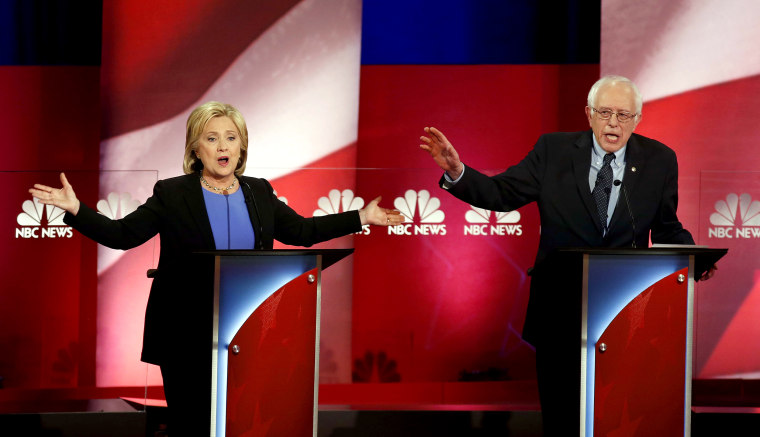

"It is the kind of criticism that we've heard from Senator Sanders about our president I expect from Republicans," Clinton said in a debate.

Sanders shot back: "Madame Secretary, that is a low blow. One of us ran against Barack Obama. I was not that candidate."

In what was now a tradition, South Carolina again became the first test of each candidate's strength with black voters. Sanders didn't have much support from the state’s black leaders — Rep. James Clyburn said Sanders hadn't asked him for an endorsement — but he did come in with a head of steam after nearly winning Iowa and then wrecking Clinton in New Hampshire. Here was his chance to prove that he really was breaking through with black voters — and that he really did have a chance of winning the nomination.

Instead, he got crushed.

South Carolina's Democratic primary electorate was 61 percent black — up from 47 percent when the primary was inaugurated in 2004. Among those black voters, Clinton’s margin of support was staggering: 72 percentage points, 86 to 14 percent, according to NBC News’ black voter data analysis.

For all of his efforts since the summer before, Sanders had made essentially no progress. It established a pattern that held throughout the primaries. The margins weren't always quite as lopsided, but they were unfailingly decisive. Black voters made up more than one-quarter of all Democratic primary voters nationally, and they were instrumental in supplying Clinton with what became an insurmountable delegate lead.