Marty Culpepper has always been a tinkerer. Growing up in Iowa, he spent a lot of time in his grandfather's junkyard and learned to draft designs at his high school's machine shop. Before COVID-19, he often spent his downtime with his kids working on his car and motorcycle.

For years, Culpepper has been known as the "Maker Czar" at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he's a professor of mechanical engineering and director of Project Manus, a research and development office dedicated to helping create and expand access to technology.

When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, that work came to a stop. Instead, Culpepper and his colleagues across MIT began participating in weekly brainstorming sessions on Zoom, working through ways they could apply their expertise and contribute solutions.

MIT is well known for taking a hands-on approach to complex problems. Much of the radar technology that helped the Allies win World War II came out of MIT's Radiation Laboratory. Later, the university's researchers were key players in the space race and pioneered electrical, aeronautical and nuclear engineering.

Culpepper said building is just as important as imagining at MIT, where the school motto is "mens et manus," which means "mind and hand." "One of the strengths of this place is being able to couple both the very hands-on and the highly theoretical to move things forward really quickly."

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Face shields for health care workers first came up as a potential coronavirus project for Culpepper's group because they are a low-hanging fruit. They are in short supply but are far less complicated than other manufactured items, like ventilators.

Face shields, Culpepper thought, could be scaled quickly to meet the crushing demand.

"We could have taken time to make them more elaborate, make the Cadillac of face shields," Culpepper said. But when it comes to design, he said, "simple always wins the day."

The disposable plastic shields are intended to be worn over a health care worker's mask to protect against patients' coughs, sneezes and sweat. "It'd be like a double whammy. Not only protecting people, but prolonging the life of the mask."

A team of about 100 people from across MIT participated in the design and production — recognizing early on that to make a significant impact, their design had to use accessible materials at the lowest cost possible in order to scale quickly.

At home, Culpepper immediately began sketching out designs and feeding them into the laser cutter in his basement workshop. With the help of his teenage daughter and son, the group had prototypes ready to try out in a matter of hours.

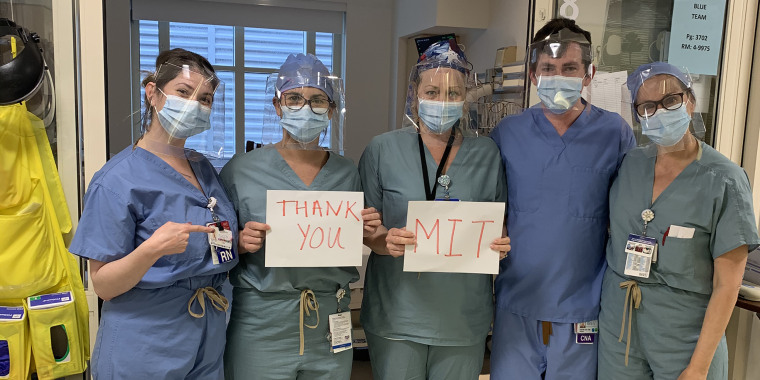

In about a week's time, those early prototypes were shared with emergency workers, nurses and doctors at a variety of Boston-area hospitals, and real-time modifications were made based on their feedback. Culpepper said that the current model is the 28th version of the shield and that it incorporates such suggestions as extending the shield's sides and shortening the length to improve mobility and protection.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

One of the doctors instrumental to the project was Culpepper's colleague Dr. Elazer Edelman, who organized health care workers' feedback process. Edelman, the director of MIT's Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, is a cardiologist treating COVID-19 patients.

In accordance with MIT's mens et manus motto, Edelman said, "you have to understand what society needs and then base whatever you're working on societal needs."

With a fast-moving crisis like the coronavirus, speed and economy are crucial to meeting society's needs. The team soon connected with Polymershapes, a manufacturer in Tyngsborough, Massachusetts, able to secure the materials and begin production while keeping the price at $2.79 per shield, well below the industry average.

Polymershapes and a coalition of partners across the country and internationally are now making the shields, primarily for health care providers, emergency medical personnel, urgent care clinics and other groups that need them for COVID-19-related use. Polymershapes said that health care workers' orders will always be moved to the front of the line but that individuals are also able to contribute shields to organizations of their choosing once they have been vetted and given permission by those places.

Today, Polymershapes' facility in Massachusetts is producing 100,000 face shields a day, but Culpepper said that "the process was built to be scalable to up to 2.5 million to 3 million shields per day" using a dozen or so facilities and that "you could easily go to 10 million per day" with the support of enough facilities.

Polymershapes' general manager, Derek Gagnon, said the company plans to make the shields regionally throughout North America, Canada and Mexico.

"Our goal is to make as many as these as quickly as possible so we can get them to the people who need them as quickly as we can," Gagnon said.

Culpepper likens the die-cutting manufacturing process to using a metal cookie cutter of sorts — punching shields out from plastic sheeting at warp speed. The form can then be bent into a 3D shape in under a minute and secured with an elastic tie.

Shipped flat, more shields can be deployed at a time. "In a box that's 14 by 20 by 6 inches, we can fit 250 of these things. You can deliver 1,000 of these in a Prius easily if you need to," Culpepper said.

MIT and Polymershapes partnered to donate the first 100,000 face shields to health care workers in Massachusetts, and orders are being sent out to hot spots like Louisiana, the West Coast and the Midwest.

On Monday, MIT and Polymershapes dropped off more than 18,000 shields at Boston Medical Center, Tufts Medical Center and the Boston Fire Department.

The shields are just the first products of a series of concurrent and overlapping initiatives being worked on by Culpepper's and Edelman's colleagues at MIT. Said Culpepper: "This is a long fight."

Designs for masks, testing swabs and ventilation devices are all in process, in addition to medical research focused on why the virus acts the way it does, means of mitigating the disease, coming up with therapies and coming up with vaccines.

Culpepper and Edelman said the spirit of the initiative is anchored in MIT's long history of stepping up during crises.

"We do research," Culpepper said. "We learn how to do new things. But then you've got to be able to make them. And if you can make them and you use new knowledge, you can bring new things into the world that improve the human condition."