The black-and-white image — Coretta Scott King, veiled and weary, seated in a church pew cradling her daughter while looking toward the out-of-frame tragedy, her husband’s body — won its photographer the Pulitzer Prize in 1969, a year after it was taken.

It was the first Pulitzer awarded to a black photojournalist.

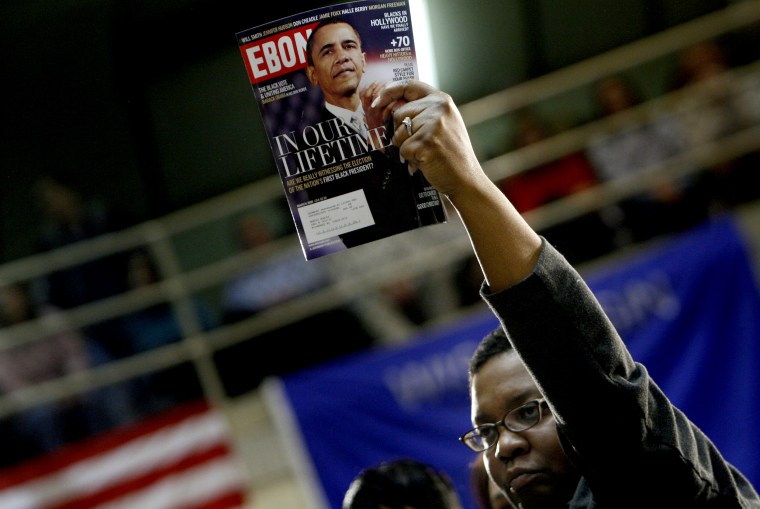

Now, on Wednesday morning, that picture and thousands of others from the photo archives of Ebony and Jet magazines will be auctioned in a private sale in Chicago, with the results likely to be made public on Thursday. The collection is considered the most extensive photographic record of black life in America in the second half of the 20th century.

The sale, part of a Chapter 7 bankruptcy action, is no ordinary liquidation. It has produced anxiety among historians and art experts, with some fearing the archive’s most sensitive images could wind up with a bidder who puts them on drink cozies or makes them available to hot-take blogs or those with a penchant for reckless comparisons. Much like the publications that produced the archive, which today exist as online shells of their former print selves, the archive sale is a commercial endeavor with social meaning. And, it comes, experts say, at a troubling time for minority groups in America.

“Ebony had the power to publish information of both great significance and minor meaning — and with that, change the narrative about black people in the United States, which it very much did,” said Brenna Wynn Greer, a historian at Wellesley College.

“Without that kind of vehicle, there’s this pressing question: Who or what is responsible for that now, at what is clearly a difficult time? Who or what is going to reliably publish the images, the stories, the editorials that challenge our otherness?”

In a poll released this month, 45 percent of young black Americans and 40 percent of Latino young adults told researchers with the Knight Foundation, a media funding and research organization, that they do not trust the mainstream media’s coverage of people like themselves. Many also described it as spotty, insufficient or often inaccurate.

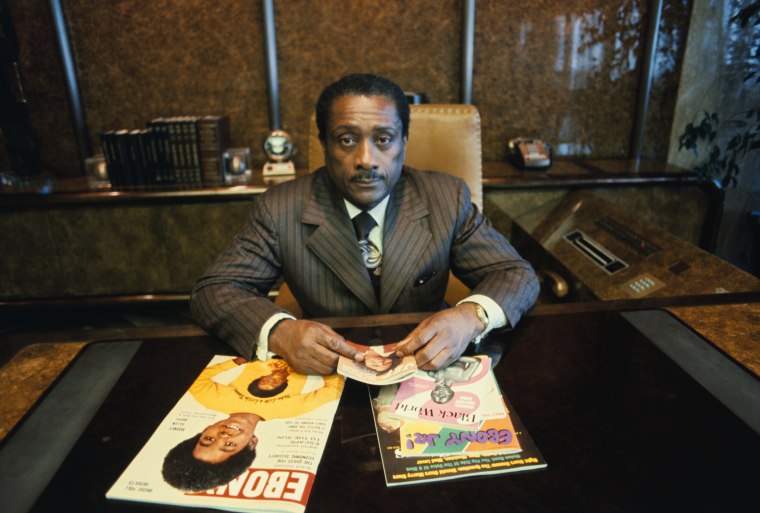

Johnson Publishing Company, creator of Ebony and Jet, got its start in 1940s Chicago, after founder John Johnson borrowed $500 against the value of his mother’s furniture. The grandson of slaves, Johnson had moved to Chicago from Arkansas with his family in the 1930s, part of the Great Migration, because Johnson’s hometown had no high school that black teens could attend. While working part-time in college, Johnson hit upon an idea, a kind of Reader’s Digest for black America. That publication, Negro Digest, began in 1942. But it was Ebony, a wide-net lifestyle monthly that debuted in 1945, modeled on Life magazine, and Jet, a news and events weekly first published in 1951, that became the commercial center of Johnson Publishing.

From the beginning, Ebony published images of black soldiers returning from World War II battlefronts, which spoke volumes about a national embarrassment: Once returned, black veterans who fought for liberty and equality abroad had a tenuous claim to both at home.

In 1955, Jet published images of the mutilated body of Emmett Till, a black Chicago boy who was tortured and murdered by white men during a visit with family in Mississippi, making plain the nature of American racism and its tolerance for violent barbarism. It was a story and a horrific set of pictures that almost no other publication would have considered publishing at the time. The black-owned Jet could and did.

The magazines also featured stories about black scientists, engineers, doctors, bankers and lawyers, recipes perfected in Ebony’s test kitchen, and narratives about athletes, art, film, music and celebrities. There were photo essays and stories about civil rights activists, as well as pioneering integrators, singing, playing and just being with their families at home.

The publications, more often than not, featured light-skinned models, celebrities in many shades and stories focused on heterosexual and middle-class, nuclear families. At Johnson’s insistence, they all but overcorrected for the stories of black suffering or dysfunction that were overrepresented elsewhere. Ebony and Jet shone a light on the accomplished, what today gets labeled #blackexcellence. The publications also ran pictures of drag queen balls and other parts of black life illuminated in few other places, including black-owned newspapers. Together, the magazines countered stereotypes about black Americans still in circulation today.

“What Ebony and Jet did was not just tell these stories not told,” Greer said. “Ebony, in particular, through the images it pushed out all over America each month, popularized ideas of African Americans that undergirded belonging, the idea that African Americans were Americans, normal and full human beings who existed and had a claim to a complete citizenship.”

For decades, Ebony and Jet had no national, sustained competition. Black readers were hungry for stories about black life, and there were few other places to find them. At its peak in the 1980s, Ebony was a standard display item in millions of black homes and businesses. Its monthly circulation climbed to almost 2.5 million and Jet sold, on average, a half million copies each week, Greer said.

Those numbers made it clear to advertisers — the biggest source of Johnson’s revenue — that there was a largely ignored black American consumer market. That, in turn, created work for black journalists, as well as ad men and later women able to build campaigns aimed at black consumers. Eventually Ebony and Jet helped to create demand for companies with culturally specific marketing expertise.

When Johnson died in 2005, he left Johnson Publishing to his daughter, Linda Johnson Rice, in a different environment. America had publications like Essence, a black women’s magazine, and Black Enterprise, a business publication, on newsstands. It had seen others, such as the black newsmagazine Emerge, collapse. And there was the internet.

Johnson Publishing struggled, and in 2016 it sold Ebony and Jet to a black-owned private equity company, which has run into its own financial problems. Right now, the magazines exist only online, not in print.

“The silver lining is, if there is one, is that The New York Times will today take up the subjects of its stories,” said Greer, author of the book, “Represented: The Black Imagemakers Who Reimagined African American Citizenship.” “But, they just might not be on the front page.”

Johnson Publishing, for decades one of America’s largest black-owned businesses, filed for bankruptcy April 9. The company had retained control of Ebony and Jet’s archive, but the cost of maintaining the archive was unsustainable, said Miriam Stein, a lawyer and court-appointed trustee overseeing the sale.

A recent appraisal valued the collection at about $46 million, Stein said. Bids could begin as low as $12.5 million.

Hilco Streambank, an intellectual property valuation company that helped organize the archive’s sale, “went after collectors, high net worth individuals, family offices, museums that have publicly made expressions of interest or concern for the African American community,” said Gabe Fried, the company’s CEO.

Fried could not disclose who had submitted advance bids but said interest appeared intense.

In a final wrinkle, attesting to the significance of the archive, the collection’s pending sale began the day Tuesday on the online front page of The New York Times.