New Hampshire authorities are investigating Merrill Lynch and at least one former top broker over customer complaints of alleged misconduct that resulted in staggering losses, according to multiple sources familiar with the investigation.

According to the sources, the state regulator has approached Merrill Lynch, a subsidiary of Bank of America, with its findings. In addition, two sources say settlement talks are underway.

A spokesman for the New Hampshire Bureau of Securities Regulation declined to comment, while a spokesman for Merrill Lynch said the firm “does not comment on the existence of regulatory inquiries.”

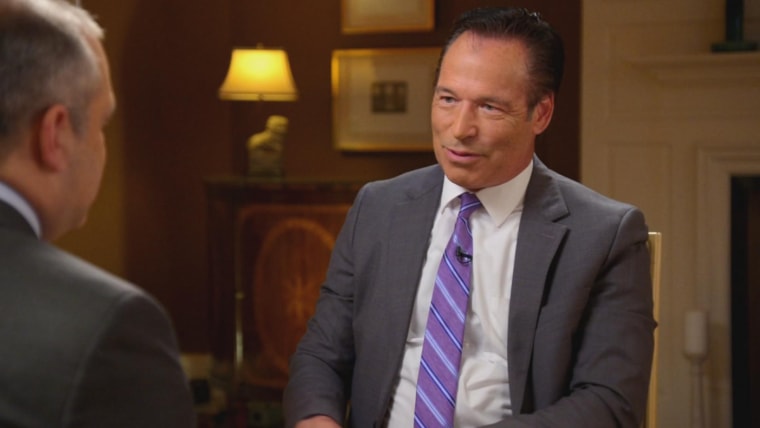

The disclosure of the investigation ison Charles Kenahan’s Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) BrokerCheck report, which says “the state of New Hampshire is conducting an investigation into certain trading practices of Mr. Kenahan.”

One of Kenahan’s former clients who alerted the state securities regulator of the alleged wrongdoings is Craig Benson, New Hampshire’s governor from 2003 to 2005.

“I certainly didn’t sign a document and say it’s OK to steal from me,” Benson told CNBC. “This is a fight I never chose. ... “Both Bob and I caught Merrill Lynch with our wallets in their hands.”

Bob is Robert Levine, a long-time friend and business partner who has already received a record $40 million payout from Merrill Lynch after the firm decided to settle allegations of unsuitable investment recommendations, excessive trading and misrepresentation brought by Levine through a FINRA arbitration complaint. Levine alleged in his complaint he sustained damages of more than $100 million.

A CNBC investigation obtained FINRA arbitration documents that contain allegations of widespread misconduct by two former top Boston-based Merrill Lynch brokers. These allegations include excessive trading, unauthorized trading, overcharging commissions, failure to supervise and breach of fiduciary duty.

The arbitration documents show that initially, Merrill Lynch argued that Levine was a sophisticated investor who approved every trade. But following a 2018 hearing before a FINRA arbitration panel, the firm agreed to the settlement without admitting wrongdoing.

FINRA arbitration is not a public forum and is used as an alternative to litigation or mediation in order to resolve a dispute.

Benson has filed his own FINRA arbitration claim, which is pending, against Merrill Lynch and two of the firm’s former brokers, Kenahan and Dermod Cavanaugh, alleging losses of more than $50 million and market-adjusted damages of over $100 million.

“We disagree with the claim that has been filed,” a spokesman for Merrill Lynch said in an emailed statement. “This is a case that doesn’t add up: a sophisticated, high net worth investor who claims to have been unaware of activity in their account for 11 years.”

The firm’s stance on Benson’s case is similar to the one it initially took in Levine’s case — that Benson was a sophisticated investor who approved every trade, which Benson denies.

“If I wanted to day-trade my own account, I would’ve done it myself. I didn’t need to pay $26 million to Merrill Lynch to do it,” Benson said.

Levine and Benson say they trusted their longtime friends to responsibly manage their wealth.

“He knew everything about Bob's and my financial situation, where everything was, how it was set up, how we did the taxes,” Benson said, referring to Cavanaugh.

They allege that their trust was grossly misplaced and say they have collectively lost around more than $200 million at the hands of Merrill Lynch and their advisers.

″[My] account was churned in large part for the benefit of generating commissions that benefited both Charles Kenahan, Derm Cavanaugh, but mostly Merrill Lynch,” Benson said.

Churning is an illegal practice in which a broker engages in excessive trading in a client’s account to generate commissions.

CNBC could not reach Levine for a comment. Repeated calls and emails to his attorney over several months were not returned.

Cabletron Systems

Levine and Benson are highly accomplished and successful businessmen. They built their wealth together, from the bottom up — something Levine calls in his arbitration filing the “quintessential American success story.”

In the early 1980s, the two friends co-founded their company, Cabletron Systems, out of Levine’s garage after discovering a niche market in the cable industry for companies that needed custom lengths of cable, delivered quickly.

“What started as something that we’d be able to save for, in my case, I wanted a refrigerator and a freezer, Bob wanted a little bit more than that. And we thought we’d sell a few things and be done. Turned out, it went to 7,000 employees and $1.6 billion in sales, and listed on the New York Stock Exchange,” Benson said.

Merrill Lynch was the underwriter for the company’s initial public offering in 1989.

In 1990, the cable and local area networking equipment manufacturer was named Fortune Magazine’s number one stock for return on investment. Cabletron’s stock price went from $16 to $23 per share that year, giving the company a market value of around $600 million. By 1997, when Levine stepped down as CEO, the company had grown to a $1.5 billion company, making Levine and Benson very rich, with millions to invest.

Both men acknowledge they are not experts on the market and that’s why they sought a financial adviser to manage their assets professionally. Levine says in his complaint he had little experience with finance or investments prior to the Cabletron IPO. Benson, who obtained his MBA from Syracuse University in 1979, said he knows balance sheets, income statements and cash flow but had never been a professional investor.

“I’m not a trader,” Benson said. “I’m not an investment professional, Merrill Lynch is, and that’s why I hired them.”

Full trust in their brokers

The two met Kenahan through Cavanaugh, Cabletron’s accountant in the years before the IPO. After leaving Cabletron, Cavanaugh began a career in the financial services industry, and in 1999 began working at a Boston-based branch of Morgan Stanley, according to his employment record on the FINRA site.

At Morgan Stanley, Cavanaugh partnered with Kenahan, an experienced financial adviser who was licensed in 1985. Kenahan, who is also an accomplished sailor and won the Swan 42 U.S. sailing championship in 2015, is described by Benson as “gregarious,” and someone who “enjoyed the finer things.”

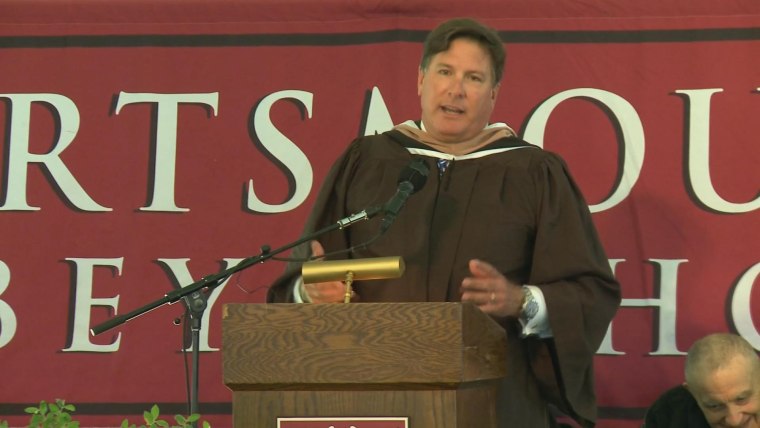

At the height of his career, Kenahan appeared to be the epitome of success. He was described by the Newport, Rhode Island, news site RhodyBeat.com as being the head of one of the country’s largest wealth management teams for Merrill Lynch. He was even asked to deliver the 2017 commencement speech at the prestigious Portsmouth Abbey School in Rhode Island, where his three sons graduated in 2012.

“One of the reasons I’m so happy in life, and I truly am a happy guy, is that I do try to live my life with as much humility as I can,” Kenahan told the graduates.

“He seemed like a nice guy and he seemed like he knew what he was doing,” Benson said about his first impression of Kenahan.

Levine and Benson said they thought they had found a financial adviser they could trust and that Cavanaugh and Kenahan would act in their best financial interests. So, Levine and Benson decided to move their individual investment accounts to Morgan Stanley and into the care of the two men. According to arbitration documents, Benson’s accounts with Kenahan and Cavanaugh totaled approximately $200 million, while Levine’s accounts totaled around $180 million.

Kenahan told Levine the goal would be to keep his accounts safe, assured him that the accounts would never be exposed to a high concentration of a single stock, that his investments would be a mix of stock and bonds, and that his commissions would be lower than what he paid to his former financial advisers, according to Levine’s FINRA arbitration filing.

Similar assurances were made to Benson, according to his claim, which also says he made it clear to Kenahan and Cavanaugh that he wanted to avoid trading strategies that would result in short-term capital gains.

In late 2007, Kenahan and Cavanaugh had an offer to move to Merrill Lynch. In his arbitration claim, Levine says Kenahan “explained that in terms of the investments, everything would be the same and that Bob could expect the same low commissions.”

Benson said he remembers receiving an urgent call from Kenahan, who later came to Benson’s house with stacks of papers that needed to be signed in order to move his accounts from Morgan Stanley to Merrill Lynch.

“The pressure to do it was now,” Benson told CNBC, adding he was given little to no time to read and review the documents with counsel but signed them anyway because he trusted Kenahan. Ultimately, Levine and Benson moved their accounts, collectively worth hundreds of millions of dollars, to Merrill Lynch.

In his complaint, Benson says neither Kenahan nor Cavanaugh disclosed to him that the brokers’ compensation at Merrill Lynch included multimillion-dollar loans that would not have to be repaid if the brokers hit certain predetermined commission targets. Such loans, called “Promissory Notes” or “Employee Forgivable Loans,” are legal and are common practice on Wall Street.

However, what Benson alleges happened next is not legal. For the next decade, Benson says, Kenahan and Cavanaugh churned his account — excessively trading in his account in order to generate increased commissions.

Forensic account analysis

“Merrill Lynch made $26 million in fees to lose me $5 million,” Benson told CNBC. “But if I had put that money in a passbook savings account, let’s say, it would have been a $50 million gain.”

That analysis is based on a report compiled by Craig McCann, founder and principal of Securities Litigation and Consulting Group. McCann was hired to do a forensic audit on Benson’s investing accounts and was also an expert witness for Levine’s case.

“We sent the data to him and then he sends back a report,” Benson said. “It took me about two months to open the box, ’cause I didn’t want to admit that there was really a problem.”

However, once he reviewed the extensive report, Benson says he realized there was indeed a problem.

In his arbitration claim against Merrill Lynch, Benson says he sustained damages in excess of $50 million, including short-term equity trading losses of over $20 million and more than $15 million in excessive trading costs. McCann’s analysis found that if Benson’s money had simply been put into an S&P 500 index fund and left to grow, he would have earned more than $100 million.

“I think Merrill Lynch has to be held accountable for what they did,” Benson said.

Benson also alleges that Kenahan executed thousands of trades, most of which Benson says he knew nothing about, which resulted in tens of millions of dollars of additional losses. Among the trades he says he never authorized were small-cap stocks in China.

“I see a lot of trades and millions of shares, and things like Want Want China and Bank Mandiri,” Benson said.

The forensic analysis showed that the trades in Want Want China, a Shanghai-based rice cracker and snack manufacturer, alone generated $1 million in commissions.

Benson acknowledges he did not always read his account statements.

“I get about 300 or 400 emails a day, and then multiple, many multiple phone calls a day. It’s just, it’s hard to keep up with all the paperwork that’s generated,” he said. But he maintains that he thought he could trust his brokers.

Levine also alleges his accounts were churned, saying in his filing that “the trading defies logic, except to the extent that it was obviously designed to further the interests of Kenahan and Merrill Lynch at [his] expense.”

Levine’s record settlement

It was Levine who first uncovered suspicious trading activity in his Merrill Lynch accounts after deciding to move the majority of his accounts back to Morgan Stanley, his claim details.

“I thought Charles had just done a poor job with my account, I had no idea I had been defrauded,” Levine said in the filing.

In late 2017, Benson said he received a call from Levine to tell him about the issues he discovered, and that there appeared to be evidence of improper activity and self-dealing.

“He said, ‘Charles is taking advantage of me. You better check your portfolio,’” Benson said.

Seeking to recoup some of his losses, Levine filed an arbitration claim with FINRA, the industry’s self-policing regulatory agency, against Merrill Lynch and Kenahan. The allegations include relentlessly churning his accounts for more than $26 million in commissions, fees, margin interest, concessions, mark-ups and mark-downs, as well as gambling more than $20 million of Levine’s money on a single penny stock, resulting in more than $16 million in losses on that stock.

“No one, not myself nor anyone that I knew, suspected Charles because everyone thought he was my friend and a caring investment adviser. He would only do the right thing for me, and I thought would be supervised by Merrill Lynch,” Levine said in his statement of claim.

“Kenahan had an absolute duty to refrain from excessive trading, charge reasonable commissions, to only recommend securities that were suitable, and to refrain from self-dealing,” Levine said in the FINRA arbitration filing. Adding that Kenahan “failed on all counts.”

Levine says the monetary damages he suffered at the hands of Kenahan and Merrill Lynch exceeded $100 million.

Merrill Lynch fights the allegations

Merrill Lynch aggressively fought the claims. In a brief obtained by CNBC, it said Levine’s case “fails as a matter of law,” and that the “astronomical monetary award” he sought had “no basis.” It referred to his statement of claim as a “fantasy, not reality.”

“As the panel will see, this entire case boils down to a false allegation: Bob Levine’s claim that he was deceived for more than a decade about the purchases and sales in his Merrill Lynch brokerage accounts,” the filing says.

Merrill Lynch added that “every legal theory in this case requires Claimants to prove that Merrill Lynch executed trades that Mr. Levine did not know about and did not want — and then lied to Mr. Levine about it. … There is no such evidence because that never happened.”

In 2019, the case eventually went to a final hearing in front of an arbitration panel, and despite the strongly worded assertions by the firm denying Levine’s allegations, Merrill Lynch decided to settle, before the arbitration panel announced its decision, for a record $40 million. The settlement is the largest single payout to an individual claimant in at least a decade, according to an analysis of FINRA’s BrokerCheck system data done by McCann’s Securities Litigation and Consulting Group.

Merrill Lynch fired Kenahan in July, following the final arbitration hearing, citing “customers’ allegations of unauthorized trading, unsuitable investment recommendations and excessive trading,” his BrokerCheck report shows. CNBC has learned that the firm is still paying for his legal defense.

Attorneys for Kenahan and Cavanaugh declined to comment for this story. However, Kenahan’s BrokerCheck report does include his comments on the matter. That section states that “the transactions giving rise to the customers’ allegations were executed at the customers’ direction. The allegations resulted in arbitrations and settlements. I was not a party to the arbitrations; I had no say in the firm’s decision to settle the claims; and I was not asked to make any payment as part of the settlements.”

It can happen to anyone

Benson says his story should be a cautionary tale for anyone who uses a financial adviser to oversee their wealth.

“If they can do it to me who has a big account and served as a governor of a state, who else can they do it to?” Benson told CNBC.

Louis Straney, who testified as an expert witness in Levine’s case and is a consultant for Benson, says the responsibility is supposed to go beyond the individual broker.

“It really is the firm’s job to supervise all of their associated persons,” said Straney, a managing partner at Arbitration Insight. “It is not the duties of the individual investor to supervise themselves.”

Levine also alleges that Kenahan, being a “huge producer” for Merrill Lynch, could have played a role in the firm turning a blind eye to his “profitable behavior.”

Merrill Lynch “had an absolute duty to supervise its registered representative, Charles Kenahan, and it utterly failed to do so,” Levine’s claim says.

For Benson, his case is scheduled to be heard by a FINRA arbitration panel located in New Hampshire in September.