(Inside Science) — Stepan Gorgutsa had a technology in need of an application. Gorgutsa, an optics engineer, knew how to make fibers for the telecommunications industry and had just started migrating the idea of flexible fibers to textiles. But he didn’t quite know the best way to apply the textiles until he met with the director of research at the teaching hospital at Université Laval in Quebec City, Canada, where he worked.

There, he learned that a nurse is assigned to monitor newborn babies’ respiration and heart rate for the first 24 hours of life. The problem is that monitoring usually requires devices to clip onto babies — something that often causes infants to scream and squirm. It sparked an idea: a monitoring sensor that didn’t constrict the user, and was nearly invisible.

From there, Gorgutsa and his team worked to create a T-shirt that can monitor heart rate and respiration. The design must thread a proverbial needle — it can’t be restrictively tight, but it still has to pick up signals from a wearer. “The idea is that it feels and acts like a normal shirt,” he said.

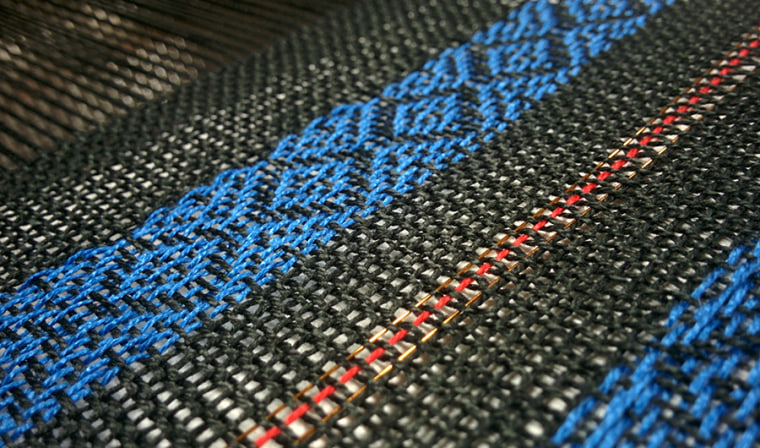

The techy T-shirt, which was reported in last month’s issue of the journal Sensors, has no wires or electrodes. The shirt has a flexible antenna sewn into it at chest level.

“When you breathe, you change the volume of the air in your lungs, and the electric properties of air are different from electric properties of [the] body,” said Gorgutsa. “Since people breathe in [a] repeatable way, this pattern can be detected.”

The researchers coated the fibers in a special water-repelling treatment and tested it by washing the T-shirt more than 20 times. They plan to create dozens of the shirts to be tested in clinical settings and compared with traditional hospital equipment used to monitor respiration.

Gorgutsa's shirts aren't the only health-monitoring garments in development. Researchers from different backgrounds are converging on new ways to diagnose or monitor people with clothing, even in remote places. Eventually, clothes like this may help emergency first responders, people in sleep clinics trying to monitor restrictions in sleep and, of course, newborns.

Newborn babies were also the inspiration for Sona Shah, an entrepreneur based in Chicago who in 2015 was a graduate student in a program that combined health care, engineering and international development. She read about neonatal infant mortality, and was surprised to discover one reason it was so much higher in low-resource settings:

“There are so many critically ill babies, and not enough people to watch them,” she said. Nearly 3 million babies die in their first month of life every year, and 98 percent of these deaths occur in the developing world.

Related: Watch This Jet-Powered Exosuit Turn Inventor into Real Life Iron Man

Shah and her co-founder created a baby hat that doubles as a wearable vital signs-monitor to quickly identify when newborns are in distress. The hat keeps tabs on a baby’s pulse rate, oxygen saturation and temperature -- data that are typically monitored in a modern hospital setting, but hard to collect in more resource-challenged facilities.

The information is then sent to a tablet, where one nurse can see the vitals of each patient in the room. “Ultimately we hope to extend what we are doing to rural settings, including a mobile app so a doctor who is not even in the room can monitor patients,” said Shah.

There are a few things that set Neopenda — the company Shah started — apart from other baby-monitoring systems. Shah said the device is clinical-grade, and its power lasts 5-7 days. Each hat only costs around US$75; the company is planning to sell them in packages and include a tablet with each batch. They are launching the product first in Uganda, and they hope to expand to other settings where resources are scarce.

Related: Godlike 'Homo Deus' Could Replace Humans as Tech Evolves

Clothing is by far the most interesting way to get information from the human body, said Jesse Jur, a textile researcher at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. “Sure, we already have patches and wristbands,” he said. “But what is different about a garment is you have access to a much larger surface area against your skin. In addition, you can make your electronics invisible.”

Jur’s lab has created iron-on electronics for garments. They created a tight shirt that monitored heart performance and sent the data wirelessly to a smartphone. Other research is going into creating new types of sensors to gather information on things like stress, or environmental factors like air quality.

“Cardiovascular disease is one of the leading causes of death for fire fighters,” he said. “And monitoring stress levels and efficiencies for police officers or soldiers could be really useful.” Those applications could be an interesting stepping stone to broader applications for everyone, he said.

Related: These Smart Contacts Could Transform Diabetes Care

His lab is also working on ways that clothes can actually harvest the energy from the body to support the electronics. “The idea is that you don’t need to plug in your wearable; it just charges as you put it on,” Jur said.

He points out that around 10 watts of power are available from a person’s body heat and everyday motion. That could be more than enough power for medical devices to operate without batteries.

Eventually, everyone could be a walking environmental sensor and health data gatherer. Those data could even transform clinical trials, experts hope. And as health-monitoring clothes trickle down from first responders to athletes and students, more possibilities will open up.

“Wearable sensors are such an exciting and new space, in every setting,” said Neopenda’s Shah. “They’re getting cheaper, smaller and easier to use.”

This story was originally published on June 6, 2017.