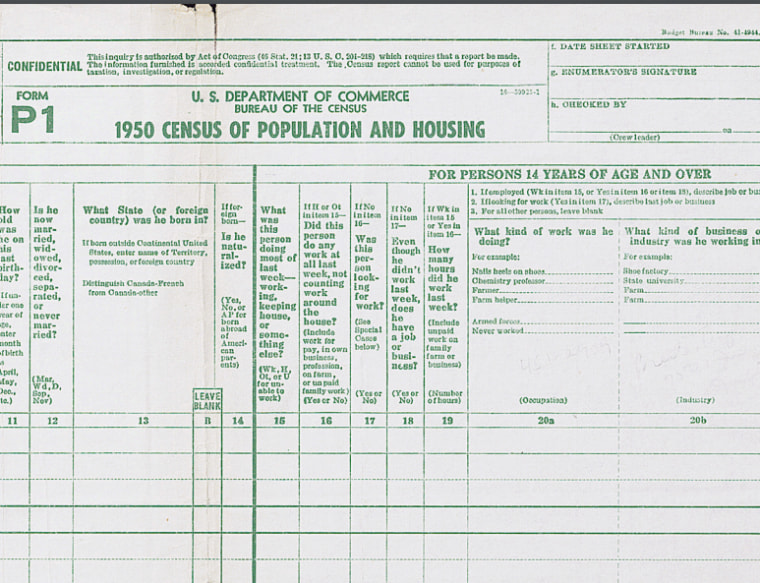

In 1950, the last time a citizenship question appeared on the census form sent to every household in the country, Harry Truman was president, gas was 18 cents a gallon, the Korean War was just beginning and Cold War tensions were simmering.

As the U.S. economy boomed and unemployment rates dropped, immigration had declined drastically thanks to the restrictive quota system imposed by the National Origins Act of 1924. That's part of the reason why the government decided to remove the citizenship questions in the 1960 census, said Margo Anderson, a leading census historian and a history and urban studies professor at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

"The census reflects the issues, the public policy concerns of the country at any particular time, and as those change so does the census questions," she said.

But a low immigrant population doesn't paint the whole picture of what happened more than half a century ago. The U.S. removed the questions in 1960 in part because innovations in survey methods revealed a more accurate way of counting the country's non-citizen population, according to Anderson.

When the Trump administration announced last month that the 2020 U.S. census would include a citizenship question, critics said it would discourage immigrants from responding and lead to an undercounting of those communities, which could cause states with high immigrant populations to lose congressional seats and federal funding.

The White House said the question is "necessary for the Department of Justice to protect voters" and enforce parts of the Voting Rights Act.

In the 1940s, the U.S. Census Bureau began testing techniques to improve sampling and created a different "sample questionnaire" that would go to a smaller percentage of the country — forming the basis for what would eventually be called the American Community Survey, which the U.S. still uses to collect data annually. The questionnaire asked fewer and more detailed questions, which the bureau found improved response rates and data over the years.

"By the 1950s, the Census Bureau statisticians realized they get better results from a well-designed sample than they do from a complete count like the census," said Anderson, who wrote a book on the history of the census.

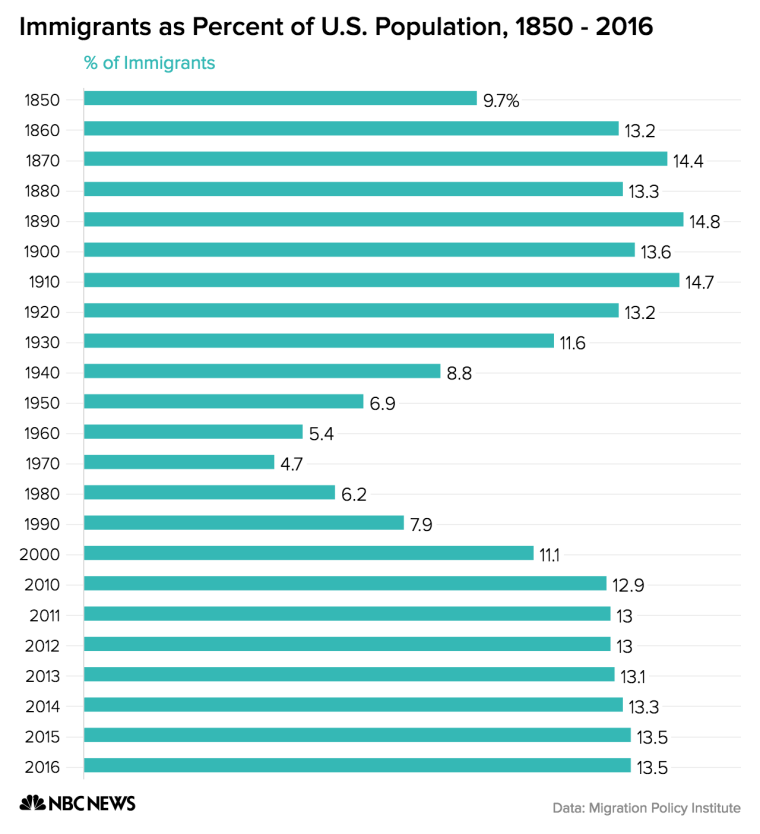

Questions 13 and 14 on the 1950 census asked, in these words, "What state (or foreign country) was he born in?" and "If foreign-born — is he naturalized?" According to the Migration Policy Institute, immigrants — which includes naturalized citizens and lawful permanent residents as well as undocumented immigrants — made up 6.9 percent of the total population that year.

When the decennial census came up again in 1960, Anderson said, the citizenship questions were no longer viewed as necessary because citizenship questions were asked on the sample questionnaire.

But as soon as the citizenship query was removed from the short-form census, immigration became more of an issue. After 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act ended the strict quota system, "immigration picks up again, mainly from non-European countries," particularly from South America, Anderson said.

In 1980, the Federation for American Immigration Reform, or FAIR, a group that advocates drastically reducing legal immigration, sued the federal government to require the Census Bureau to directly determine the status of individual immigrants in the country.

The case never took off, but the government argued at the time that "any effort to ascertain citizenship will inevitably jeopardize the overall accuracy of the population count," an argument the bureau has consistently upheld over the years.

But in a March memo announcing the Census Bureau would add the question back to the main form, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross downplayed the idea that undercounting would occur.

"While there is widespread belief among many parties that adding a citizenship question could reduce response rates, the Census Bureau's analysis did not provide definitive, empirical support for that belief," Ross said in the memo. "I find that the need for accurate citizenship data and the limited burden that the reinstatement of the citizenship question would impose outweigh fears about a potentially lower response rate."

Anderson says the Trump administration is wading back into the debate about how best to accurately count non-citizens unprepared.

In Providence County, Rhode Island, census testers have begun what is dubbed a "dress rehearsal," in which the bureau is running the only full test in preparations for the 2020 census. And the citizenship question isn't on the test.

Meanwhile, the Census Bureau's researchers acknowledged in a September 2017 memo that the current climate had stymied some of their previous pretests, finding that some immigrants in the studies raised concerns about sharing information with the Trump administration.

The census officials also noted that "fears, particularly among immigrant respondents, have increased markedly this year" and discovered that immigrant communities intentionally provided inadequate or incorrect information.

And this scenario is playing out in Rhode Island during the census tests, where the community's growing Latino population is showing reluctance to even participate in the bureau's dry-run, according to The Wall Street Journal.

"These findings are particularly troubling given that they impact hard-to-count populations disproportionately, and have implications for data quality and nonresponse," the census memo said.

Now, a multistate lawsuit filed by 18 attorneys general and several cities is aiming to halt the addition of the question, arguing that it would run afoul of the constitutional requirement that the census has to count everyone.