Jimmy Miller remembers being called “half-breed” growing up.

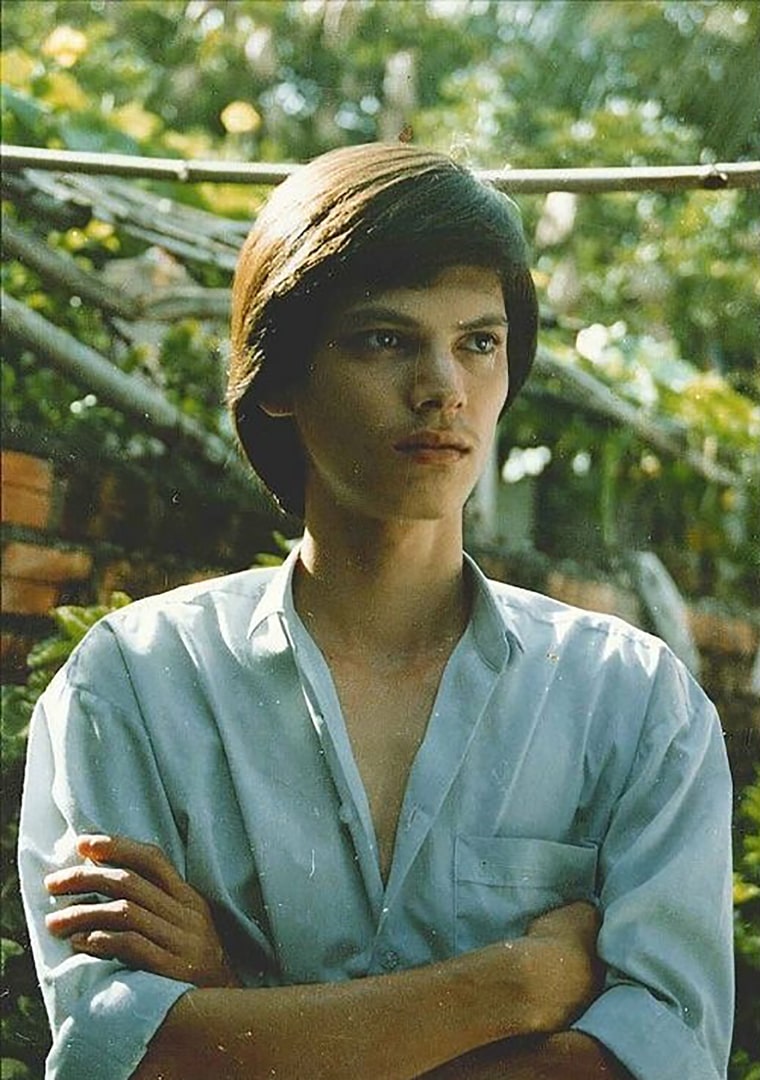

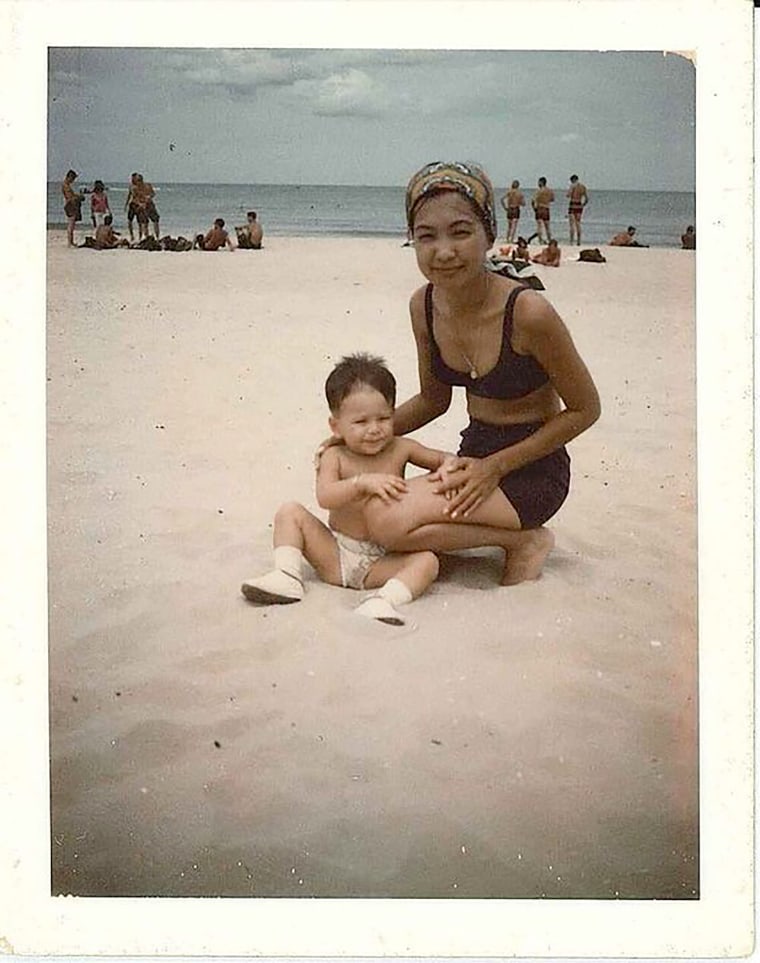

Born in 1967 in the then South Vietnam capital of Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, Miller is the child of a Vietnamese mother and an American soldier. His parents were married, Miller said, but as the war pushed on, his father was injured and sent home. For Miller and other “Amerasians” like him, life in Vietnam was full of bullying, abuse and fear of the government, he recalled.

I grew up in Vietnam...I feel the hardships of everyone. That is why I want to get them out. How can we forget the brothers and sisters still struggling in Vietnam?

“When we grow up as Amerasian, people called us names,” Miller said. “Other kids throw rocks at us or beat us. And we don't have good education.”

So when Miller heard that the U.S. had passed laws at the end of 1987 to make it easier for Amerasians and their immediate family to come to the U.S., he applied immediately. In 1989, at the age of 22, he was granted permission to move to the U.S. by way of the Philippines. After six months there, Miller and his family settled in Spokane, Washington, in 1990.

“I felt very happy that I finally came to my fatherland,” Miller said. “I finally have my freedom. I finally have an opportunity for my future.”

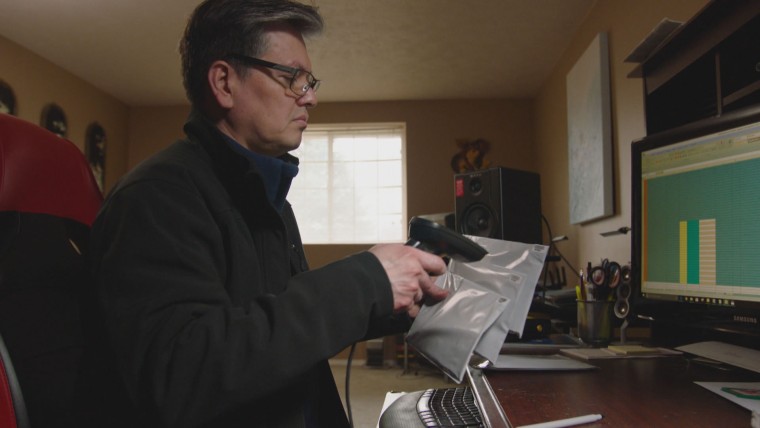

Today, Miller works to help Amerasians in Vietnam come to the U.S. through Amerasians Without Borders, a nonprofit he created in 2015. The group ships DNA kits to those still in Vietnam, helps petition for them to immigrate to the U.S. should they have a positive match, and then helps resettle and support the immigrants when they arrive in Spokane.

Congress estimated that approximately 20,000 to 30,000 Amerasians and their family members lived in Vietnam in 1987, though by 1994 more than 75,000 had left the country to resettle in the U.S., according to a report by the U.S. General Accounting Office.

Miller said he has tested 500 people living in Vietnam and estimates that there are about 400 Amerasians left in the country.

Many, including Miller, came to the U.S. hoping to find their fathers, though the process can be difficult. While Miller came to the U.S. with his mother and siblings, all they had of their father was his name, a photograph, and a letter he’d written in 1969 with no return address.

“I spent years looking for my father,” Miller said. After sending a letter to the Red Cross and hearing back, Miller thought his father had died. But in 1995, Miller’s youngest sister Trinh wanted to get him a wedding gift that he would never forget.

At the time, she was volunteering at the Spokane Public Library. She asked a co-worker how she might find someone. “This was before the internet, so he told her if she had an address, you could call the library in that town, to see if they have them in their system,” Miller said.

While they did not have a return address on the letter Miller’s father had mailed, the letter did have a postmark from Fayetteville, North Carolina.

“She called the Fayetteville library and asked if they have a James Miller on file,” Miller said. There were three. “Then she asked if any of them have a middle initial ’A‘ for Arthur, and there was just one.”

Miller’s sister called the number on file, explained who she was, and left her brother’s contact information.

Miller’s father called him, but initially asked for Phan, the younger Miller’s Vietnamese name, mispronouncing it. “I thought, ‘oh well he is looking for the guy that used to live here, so I hang up,’” Jimmy Miller said.

About 15 minutes later, James Miller called back, and said he needed to talk to Jimmy, his son. “At first I was shocked, and I still did not believe it,” the younger Miller said. “I thought it was someone who had seen my story, and they were trying to trick me.”

Not long after, Jimmy Miller’s father and stepmother flew from North Carolina to Washington, to spend a month with him after 27 years apart.

Meeting his father inspired Miller to start his nonprofit.

“I grew up in Vietnam, and I feel the hardship. I feel the hardships of everyone,” Miller said. “That is why I want to get them out. How can we forget the brothers and sisters still struggling in Vietnam?"

The process to qualify under the 1987 law is more difficult now than it was when Miller came to the U.S., he said. To qualify for an Amerasian visa, one must include an application with a “detailed explanation,” including evidence. Many Amerasians lack any information who their parents are after being put up for adoption or being abandoned by their mothers out of fear of judgment or persecution, Miller said.

“It's impossible for some of these Amerasians to know who their dad are,” Miller said. “That's how I come up with the idea and said, ’how about we give them a DNA test?’ The DNA test will not lie.”

“DNA evidence between an Amerasian and their father, and even their half sibling, is the gold standard,” John Aloia, consular section chief of the U.S. Consulate in Ho Chi Minh City, said. “That's proof positive, and that eliminates any misunderstanding or that this child is theirs or not theirs.”

When organizing his nonprofit, Miller contacted Family Tree DNA, a Texas-based genetic testing company. The partnership with Family Tree DNA has allowed Miller to purchase the kits at a lower price compared to the roughly $300 a kit normally costs.

Miller thinks the group is close to testing every Amerasian left in Vietnam. The process has taken nearly five years and has stretched from Hue in Central Vietnam to the southern city of Ca Mau.

Since 2013, Miller has helped 15 families reconnect. “Every time I see a family connect, I feel the same. I am so happy for them, like finding my own family, my own dad,” said Miller. “Every time I see them I think of my dad.”

In the last year, Jimmy Miller has helped connect a family in Yakima, Washington, with their long lost daughter and sister in Tra Vinh, Vietnam. See their full story on Dateline, June 17, 2018, at 7/6c and on nbc.com/Dateline.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.

CORRECTION (June 15, 2018, 4:46 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated the year Miller was granted permission to immigrate to the U.S. It was 1989, not 1998.