Jason Akel paced outside a junkyard on Governors Island in New York Harbor, where his son and daughter were among dozens of children gleefully dashing around with saws, hammers and nails.

“Hey, Ty, don’t destroy the structure,” Akel called over a fence as his son, Tyler, 12, sawed through a rickety wooden frame.

“I’m not!” Tyler responded, his eyes fixed on the plank he was grinding through. “I’m improving it.”

The Akels, vacationing in New York City from Orinda, California, were at the Yard — one of America’s few “adventure playgrounds.” At this one on a former military base just off of the Brooklyn shoreline, children as young as 6 scurry up piles of tires, pull the stuffing out of old office chairs and use tools to create and destroy whatever they wish. No parents are allowed inside.

The Yard is one result of a growing call to expose kids to more risk, a call that has recently played out from online parenting forums to medical journals.

The much-debated question: Can parents’ efforts to protect their children actually hurt them?

Last week, a study published in the journal Developmental Psychology found that helicopter parents — those who hover over their children — can diminish their children’s ability to regulate emotions and behavior. Concerns like these have spurred a backlash against overprotective parenting, with some parents, psychology experts and lawmakers calling for a return to a more laid-back style of child-rearing, with less parental involvement and more autonomy for kids. (This is, of course, a choice of privilege; in impoverished neighborhoods where children regularly encounter unwanted danger and adversity, few parents would actively choose more risk.)

The movement to give children more independence got a boost last month when Utah became the first state to put into effect a “free-range parenting” law.

“People recognize that the pendulum has swung so far in terms of overprotecting kids, that we’re just robbing them of the opportunities that we had to help us turn into good, successful adults.”

That legislation changed Utah’s definition of neglect, so a parent can’t be arrested for allowing well-cared-for children to walk reasonable distances alone — like home from school — even at young ages.

“People recognize that the pendulum has swung so far in terms of overprotecting kids that we’re just robbing them of the opportunities that we had to help us turn into good, successful adults,” said Utah Republican state Sen. Lincoln Fillmore, who sponsored the law. “They’re not going to have the skills that they need to navigate the world as adults.”

‘Just give your kids an old-fashioned childhood’

The free-range parenting movement was founded by Lenore Skenazy, a New Yorker who a decade ago was excoriated after she wrote a column in the New York Sun about allowing her then 9-year-old son to ride the subway and a bus home from a store alone.

Skenazy defines free-range parenting as the opposite of being overprotective: anything that gives children freedom, whether it’s sending them to the grocery store by themselves or not tailing them as they learn to ride a bike.

“It was controversial, but I was urging people to just give your kids an old-fashioned childhood,” Skenazy told NBC News.

What Skenazy dubbed free-range parenting used to be the standard — the way that Generation Xers and those before them were raised, with parents letting kids outside in the morning to play and not expecting them back home until dinnertime. If children got hurt or lost, their parents had faith that they would eventually get home safely — and more often than not, they did.

The switch to more protective parenting happened gradually, but the 1980s was a turning point, marked by high-profile crimes including the 1981 abduction and murder of 6-year-old Adam Walsh from a Florida mall. At the same time, schools became more rigorous amid fears that American children couldn’t compete globally, and some parents began to jam-pack their children’s schedules with structured extracurriculars.

“Children’s freedom to go out and explore has declined and the amount of time children are spending in school and doing homework and other school-like activities like adult-directed sports and classes has increased,” said Peter Gray, a psychology research professor at Boston College and the author of “Free to Learn.”

As parents with the time and resources to do so began to micromanage their kids’ lives, the so-called helicopter parent was born.

“Basically it’s a society that has decided gradually but overwhelmingly to look at childhood only through the lens of what could go tragically wrong.”

While violent crime has sharply declined in the past quarter-century, Skenazy said many people still parent as though danger lurks around every corner. She blames the constant scroll of headlines about abductions and hot-car deaths, as well as companies that market high-tech devices to protect children, like baby monitors that track an infant’s oxygen level at night. In this environment, it’s no wonder parents don’t leave their children’s sides, Skenazy said.

“Basically it’s a society that has decided gradually but overwhelmingly to look at childhood only through the lens of what could go tragically wrong,” she said.

Dr. Gail Saltz, a psychiatrist who writes about parenting for U.S. News and World Report, believes social media has also driven helicopter parenting, because it highlights an anxiety-inducing mix of aspirational stories and worst-case scenarios.

“There’s much more information being shared, on both wonderful things that can occur — as in whatever prize you won, whatever school you got into — and terrible things that occur all over,” Saltz said. “Kidnappings, murders and sex abuse are still relatively rare relative to the population and in some instances even rarer than before, but it doesn’t feel that way to people because they’re hearing about it in a way that they didn’t during their parents’ generation.”

The pros and cons of free-range parenting

All of this hands-on parenting raises the question of what kids are missing when adults are constantly hovering.

“From an evolutionary perspective, it’s very important to allow children to take risks,” like climbing a tree or walking alone, said Gray, the psychology research professor. “This is how children learn that they can fail and get back up, or even get hurt and survive and thrive after that.”

This doesn’t apply to children facing actual hazards. Growing up in a poor neighborhood can reduce the chances that children will graduate from high school, research has found. And true harm — abuse, neglect or other trauma — causes significant lasting effects, research shows.

Risk, on the other hand, has been proven to build resilience. Studies show risky play, like the kind in adventure playgrounds, can build social skills and encourage creativity.

The free-range parenting movement has been gaining steam, particularly after a clash between police and parents in Maryland made headlines in 2015. Danielle and Alexander Meitiv were investigated after allowing their 10-year-old son and 6-year-old daughter to walk a mile home from a park by themselves. (Danielle Meitiv is now running for her local council board on a platform of “standing up for all families” and cutting through bureaucracy).

Utah was the first state to pass a free-range parenting law, and groups in at least six other states, from New York to Idaho, are pushing similar bills, advocates say. Last year, Skenazy launched a nonprofit, Let Grow, to promote resilience in children by encouraging them to be more independent.

“To have legislation that rolls back the threshold of child neglect is a waste of legislators’ time.”

But free-range parenting also has its opponents. Daniel Patterson, a parenting coach and author of “The Assertive Parent,” believes that laws such as Utah’s put children in jeopardy.

“If you’re letting your 8-year-old walk down the street all the way to the grocery store, and you’re not sure what they’re doing or where they are, I don’t know that that life lesson outweighs the risk of what could happen, or what might happen, or what does happen,” he said. “To have legislation that rolls back the threshold of child neglect is a waste of legislators’ time.”

Politicians in Arkansas agree. Last year, members of the state House Judiciary Committee rejected a free-range parenting bill, with House Speaker Jeremy Gillam arguing that it could take less than a minute for someone to carjack a vehicle with a child left alone inside while parents ran into the store.

Those who practice free-range parenting recommend transitioning from a more regimented style gradually, so that children are comfortable.

Before allowing kids to walk home from the park alone, for example, walk with them numerous times to ensure that they know the route and understand the necessity of looking both ways before crossing streets. (The American Academy of Pediatrics says many children aren’t developmentally capable of crossing the street by themselves until they are 10 years old, but many free-range parenting advocates believe that it’s earlier than that.)

And when exposing children to risk, it’s important to follow their lead, according to Gray.

“In any kind of dangerous play, we have to distinguish what is pushed upon the child and what the child is choosing,” he said. “It’s not play if the child is not choosing.”

‘Kids are collectively much more capable than we think’

That’s not a problem at the Yard, where children frequently beg for “five more minutes” to play with saws and hammers as their parents tell them it’s time to go — and where organizers say injuries serious enough to warrant medical attention are rarely an issue.

Since the playground opened in 2016, two children have stepped on nails and some have gotten splinters, but there have been no broken bones, said Reilly Bergin Wilson, board chairwoman of play:groundNYC, the nonprofit that runs the Yard. Trained “playworkers” monitor the children, though they step in only if absolutely necessary — much like lifeguards.

“Kids are collectively much more capable than we think,” Wilson said.

Akel, the father who was watching from behind the fence as his children sawed away, worried that they were in danger — but, he admitted, they seemed to be handling it all right.

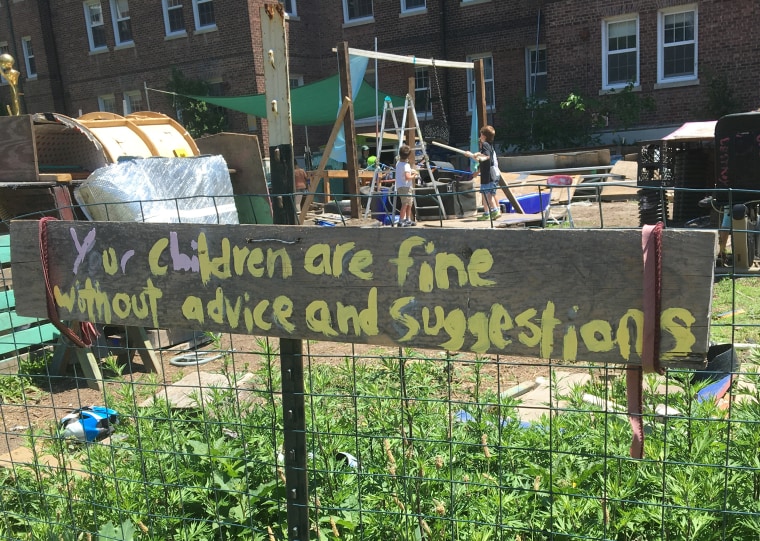

He tried to heed advice on a hand-painted wooden sign hung on the fence: “Your children are fine without advice and suggestions.”

“We’re 10 minutes in and we have hammers being swung near each other’s skulls, but so far, no blood,” Akel said. “With the splinters flying, I would almost wish they had some safety glasses. But I’m good. The sign tells me they’re going to be safe.”