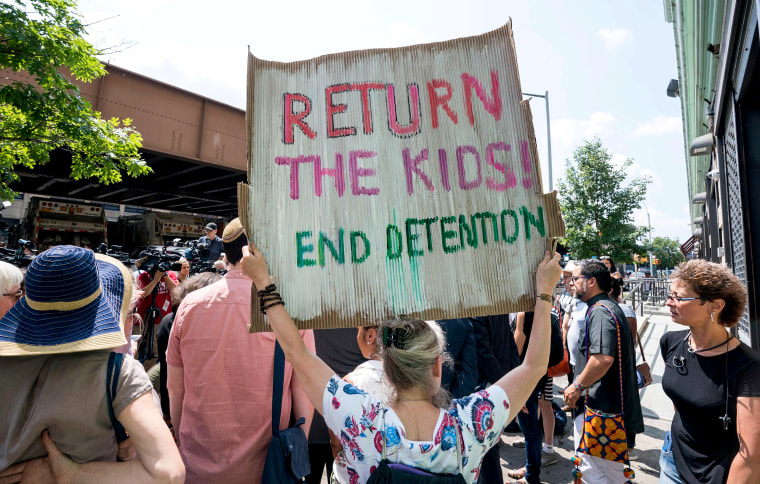

Although the news spotlight has shifted, the ordeal of families separated at the U.S. border continues.

Hundreds of children wrenched from their parents after fleeing brutal conditions still await reunification. On June 20, President Donald Trump signed an executive order meant to end the separation, but many of the children remain in limbo while plans to restore families are worked out. On June 26, a California judge ordered that kids be joined with their parents within 30 days, and children under five far sooner. Unfortunately, some adults have already been deported without their kids, making reunions even more difficult. On Monday, a federal judge ordered a temporary halt to deportations, giving parents a week to decide whether to seek asylum in the U.S. or return to their countries of origin.

Foster parents sheltering these separated children have reported seeing tremendous distress. As have the physicians, social workers and other healthcare providers who work with them.

Such adversity can leave permanent scars on human beings, particularly on kids whose vulnerable minds and bodies are still developing. The children, already stressed from an arduous journey and a plunge into the unfamiliar, suffer the wrenching disruption of the most important human bonds. Some experts have warned that kids could be “scarred for life” and develop symptoms that can even be passed on to future generations express the country’s fear and anguish at the enormity of the tragedy.

Does psychology offer anything that could help the kids be all right?

Mental health experts who study the theory of post-traumatic growth may offer a glimmer of hope in this dismal situation.

Mental health experts who study the theory of post-traumatic growth may offer a glimmer of hope in this dismal situation.

Most Americans know about post-traumatic stress and its most severe manifestation, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition the American Psychological Association officially recognized in 1980. It marked a key development in the humane treatment of those who had endured disastrous circumstances through no fault of their own. The new diagnosis brought relief and dignity to people in debilitating distress

Initially, psychologists and psychiatrists focused on alleviating symptoms of post-traumatic stress and restoring people to a functioning level. More recently, some mental health professionals have shifted their attention to facilitating positive development that can sometimes occur in the wake of trauma. The theory of post-traumatic growth (PTG) posits that, in some cases, people can emerge from stressful events with new strengths and increased resilience.

It might seem counterintuitive, even inappropriate, to talk about growth as a possible result of living through horrors like violence and dislocation. The idea that people, particularly children, can come out of catastrophic trauma stronger and possessed with more skills than they had before sounds like it must be the exception to the rule.

But there is a deep human wisdom in the idea. Some of the greatest thinkers have emphasized the potential of growth in people who have endured terrible events. Abraham Maslow, for example, known for his idea of self-actualization, held that the most important learning experiences are tragedies that force people to adopt new perspectives on life.

Human beings are powerfully drawn to narratives that illustrate such growth, from the transcendence of religious figures to the superpowers of comic book heroes. We love it that Bruce Wayne becomes Batman, a crime-fighter, after his parents are murdered before his eyes as a child. But isn’t that just fantasy?

Maybe not entirely. In the 1990s, two psychologists at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Richard G. Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun, coined the term PTG. They argue that cases of people who endure psychological struggle following crises and come out stronger are not rare as rare as you might think.

Indeed, they found that 30-70 percent of trauma survivors report at least one sign of PTG — defined by changes like a deeper appreciation of life and sense of purpose. Not only that, the psychologists found that people who surmount extraordinary challenges are more likely to find personal strength, experience spiritual evolution and perceive deeper meaning in life than people who never face trauma.

Stephen Joseph, a pioneer in the scientific examination of PTG, similarly argues in his book “What Doesn’t Kill Us,” the title of which derives from the famous saying by Friedrich Nietzsche, that something good can be extracted from grave misfortune. The focus is less about rebounding — many trauma survivors will never be able go back to the way things were — but more about reconfiguration. You might not recover your old self, but you can develop a new self.

Joseph observes that trauma does not have to be a life sentence of unmitigated suffering. He notes that only 8 percent to 12 percent of people exposed to traumatic events and less than a quarter of people involved in profoundly traumatic experiences ever reach the diagnostic threshold for PTSD. And only a minority end up with a long-lasting form of the disorder.

PTG, as Joseph and others have argued, is not the opposite of post-traumatic stress, but something that can happen alongside it. Interestingly, some researchers have found that it is often the people who show higher levels of distress in the wake of a trauma who end up having the most positive outcomes. While he acknowledges the need to address stress-related symptoms, Joseph believes that long-term recovery may often involve the creation of new meaning in life — something traditionally viewed as outside medicine’s purview.

But how does this work in children who have seen their worlds shattered, along with their sense of themselves? Kids don’t have the cognitive capabilities that adults have. Yet research suggests that those over the age of seven can and do experience post-traumatic growth, with outcomes like increased self-esteem and compassion, greater appreciation for relationships and a deeper sense of meaning or spirituality.

Research suggests that those over the age of seven can and do experience post-traumatic growth, with outcomes like increased self-esteem and compassion.

Psychologists first used the term resilience in the 1970s to describe children who, though raised in poverty and crime-stricken surroundings, were able to overcome their adversity and develop into well-adjusted young people. Resilience is related to PTG, but not exactly the same thing. Resiliency is when children are able to return to the level of functioning they had before the trauma occurred. PTG is when they show positive behaviors and perspectives that may not have been present before the trauma — such as more empathy toward others.

One study looked at children from ages 7-10 who had lived through Hurricane Katrina. Many had suffered traumatizing events such as the death of a family member, injury or homelessness. Researchers studied the young survivors and caregivers both one and two years after the disaster and looked at the children’s level of functioning. How competent did they feel? How did they view their future?

The study authors found that in addition to experiencing continuing distress, a sizable proportion of the kids reported post-traumatic growth, showing an enhanced sense of their own competence and ability to adjust in the face of hardship. Surprisingly, those who experienced the symptom of upsetting rumination, a tendency to think repetitively about a situation and its consequences, often seemed to turn out the best. The distressing thought patterns, the authors theorized, may have been a catalyst for the growth process.

Research on PTG is still in the early stages. There are many questions to be explored, such as how long the benefits last and what conditions may best promote it. But studies on children and adolescents who have undergone refugee and asylum-seeking situations, natural disasters and traffic accidents have shown promising indications of the possibilities for PTG.

As you might expect, children who have adults around them who can help them understand the meaning of events and hear their thoughts and feelings without judgment are more likely to experience PTG. The roughly 2,500 children separated from their parents after crossing the southern U.S. border have been taken, after a supposedly brief detention in Customs and Border Protection facilities (the conditions in which have been widely criticized) to long-term shelters scattered over 17 states. In some cases, they have been placed with families or sponsors while their parents await trial for illegally entering the country.

PTG techniques which may prove useful in such a humanitarian crisis include narrative exposure therapy, first developed for use with refugees. It involves having survivors create stories of their experience that are meaningful to them. Another technique is compassionate mind training, an approach to help people with feelings of shame. A therapist might ask a child to compare how they talk to themselves with how they would respond to a close friend or family member in a similar situation.

Knowing about post-traumatic growth can aid adults and caregivers who may be able to encourage children to practice skills such as telling stories, asking for help and helping others who may be hurting. It might also benefit the kids to know that their lives can hold potential as well as pain.

Trauma is a shocking and terrible experience — certainly not a positive one — and very few people would choose to live through it. But post-traumatic growth proponents hold that often something positive can ultimately arise in the struggle to deal with it.

The children caught up in the border crisis may be separated — but they need not be lost.

Lynn Stuart Parramore is a cultural theorist who focuses on the intersection between culture and economics. She is the author of “Reading the Sphinx: Ancient Egypt in 19th-Century Literary Culture” and her writing has appeared in Reuters, Lapham’s Quarterly, Salon, VICE, Huffington Post and others.