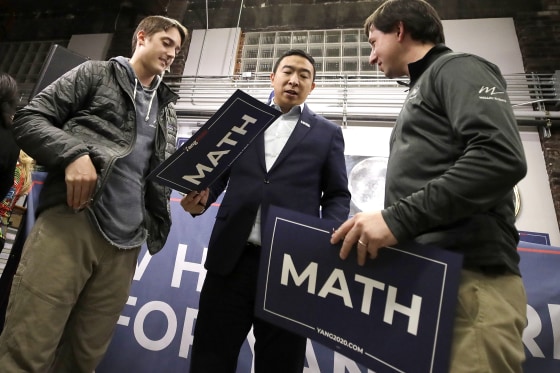

Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, who was virtually unknown 12 months ago, is currently polling around 3 percent nationally. That’s good enough to put him right on the cusp of qualifying for Tuesday's Democratic debate, but significantly lower than (most of) the six candidates who officially qualified.

While Yang may not have wide mainstream appeal — yet — he has been able to mobilize strong support from a diverse group of men who, on the face of it, would have little in common.

While Yang may not have wide mainstream appeal — yet — he has been able to mobilize strong support from a diverse group of men who, on the face of it, would have little in common. Wealthy tech CEOs, disaffected Bernie Bros and some of the most notorious Republican rabble-rousers seem to have a Yang-shaped hole in their hearts. This is, at least in part, because Yang’s message is resonating in particular with men who feel forgotten, not just by the Democratic Party, but by society at large.

For instance, conservative pundit Ben Shapiro has called the Democrat “a nice and decent human being” who is just “trying to be reasonable.” “Fox News” host Tucker Carlson dedicated an entire segment of his show to Yang — hailing him as "the political figure who is making the most sense" on the dangers of Big Tech and robotics. Yang’s campaign received so much support after his appearance on Joe Rogan’s controversial podcast (Rogan identifies himself as a Republican) that it’s still perceived as the unofficial launch of Yang’s presidential campaign.

The unorthodox praise Yang has received from conservative lightning rods makes it hard to believe that Yang is not only a Democrat, but that he believes the government should essentially distribute $1,000 a month in free money, something he calls the freedom dividend, to every single American. Yang also has been called the internet’s favorite candidate by The New York Times, partly because he has one of the most dedicated online communities on platforms where men tend to assemble, like Reddit, Quora and even 4chan.

Besides the freedom dividend, Yang addresses economic and emotional concerns affecting men right now. He often talks about struggling truck drivers and fired factory workers, and even raised alarm bells about the rise in suicide rates for cab drivers in New York, noting that “if these had been sweatshop workers in Asia making goods for U.S. consumers, it would have sparked an international response.”

“Old white men” have virtually become a slur in progressive circles but Yang seems sincerely concerned with their suffering.

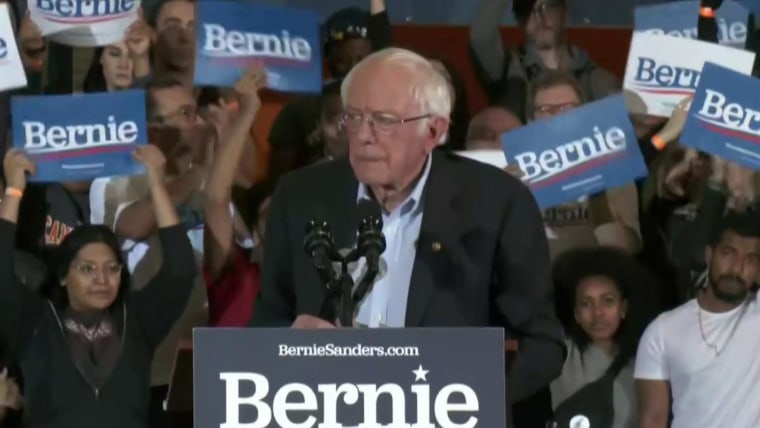

“Old white men” have virtually become a slur in progressive circles (so much so that Bernie Sanders has had to justify why a man of his race, age and gender should even be running) but Yang seems sincerely concerned with their suffering. “The group I worry about most is poor whites,” he writes in his book "The War on Normal People." “There will be more random mass shootings in the months ahead as middle-aged white men self-destruct and feel that life has no meaning.”

While vigorously supporting the expansion of women’s rights and racial justice, Yang also simultaneously demands more compassion for white men, noting in the same interview that “if the person who is suffering is a white man of a certain background, then the suffering is somehow diminished.” Before he ran for office, Yang, in his 2018 book, warned about the chaos that rising male unemployment stemming from automation could cause. Regardless of whether we’re really in as much trouble as Yang believes, his view that unemployment is a direct social threat to men has understandable cachet.

Yang is right that the consequences of unemployment rarely stay siloed. His connecting the dots between male pain and social ills like depression, suicide, intimate partner violence and domestic terrorism are backed up by data. When men are worried about being unable to make money and provide for their families, they show physical signs of stress, and researchers believe this is because they start to view their masculinity as being under threat. This in turn can push them toward curious behaviors that some researchers have labeled "masculinity-restoring activities."

Studies have even found that when their masculinity is threatened, men are more likely to tolerate domestic violence and sexually harass women, for example. While it might be useful for Yang to question whether these archaic notions of manhood should be revised, he is at least acknowledging that they exist and that they have direct consequences on our entire society.

And whether it's deliberate or not, Yang's strategy of speaking directly to lost and struggling men is paying off. His base isn’t just animated about his message; they’re enthusiastic with their donations.

Yang has described many of his fans as “shy” men who “play a lot of video games” and explains his success with these voters by the fact that he speaks their language. When I spoke to members of the #YangGang, though, it was clear that Yang’s appeal hits deeper than simply an affinity for gaming. It's not that his supporters necessarily see themselves in him, it's that they feel seen by him. Eddie Briseño, a 22-year-old college student who runs the online group “Humanity for Yang,” explained that many young men have a deep-seated fear of the future.

“When you’re a guy, you think, ‘I have to make something out of myself,’ but when those opportunities don’t exist, or won’t exist in the future, that feels awful, there is this sense of dread,” he told me. “Lack of opportunity resonates for men.”

Briseño said video games had actually helped him by providing an outlet. “You feel this sense of ‘I want to achieve something,’” he said. The games can give young men a sense of control, and while others may see these men as simply lost to “World of Warcraft,” Yang sees them as hungry for a kind of guidance they don't always feel like they have permission to ask for.

Gregory Martin Epstein, the humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT and a technology columnist at TechCrunch, said he believes Yang is responding to the quiet desire in a lot of men to express their despair. "There isn't really much of a niche in popular culture — say, on Twitter — right now, for talking about the ways in which men can be terrified of not measuring up,” he told me, adding that Yang "seems self-aware that men often suffer silently, despite their seeming dominance. He wants to do something about it, and I applaud him for that."

So whether Yang makes it to the White House — and there’s a pretty good chance he won’t — the Democratic Party can and should learn from his campaign. Young men don’t just want to be told how they’re the problem, they want to be part of the solution, and Yang is striking that balance in a way that few Democrats have.

One of the most memorable presidential debate moments thus far came when the candidates were asked on Nov. 20, 2019, about white supremacy. Rather than blaming Trump and condemning his supporters — the party line at this point — Yang alluded to the fact that many of the men joining these movements are lost. Focusing on how to productively raise boys differently to protect them from these movements may be the solution to this bigger problem.

If Democrats want to stand a chance against Trump in 2020, they may want to take Andrew Yang seriously. And perhaps literally, too.