Mateo Jaramillo sees the future of renewable energy in thousands of iron pellets rusting away in a laboratory in Somerville, Massachusetts.

Jaramillo is chief executive of Form Energy, a company that recently announced what it says is a breakthrough in a global race: how to store renewable energy for long periods of time.

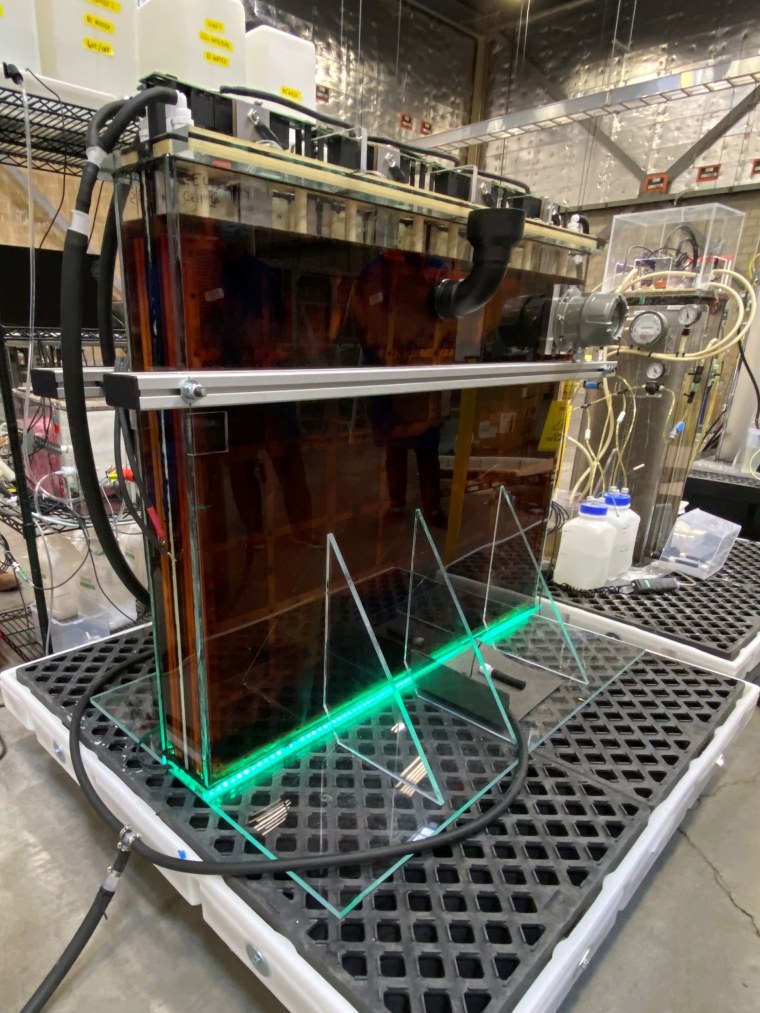

Traces of rust on iron have been a sign of decay for thousands of years. But now this chemical process — the oxidation of iron into iron oxide — forms the basis of a battery that Jaramillo said could offer a way to store energy on power grids for more than 100 hours, but at about one-tenth of the cost of an equivalent facility powered by lithium-ion batteries, the leading battery technology.

“Lithium-ion today is very cost-effective at providing energy storage for a few hours,” Jaramillo, who used to work on stationary energy storage for the electric car company Tesla, said. “But forecasting out into the future and looking at how the grid operates, we need to be able to bridge hundreds of hours.”

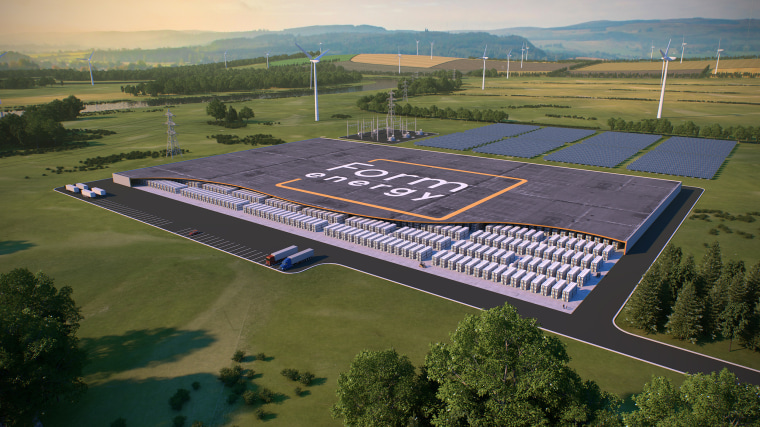

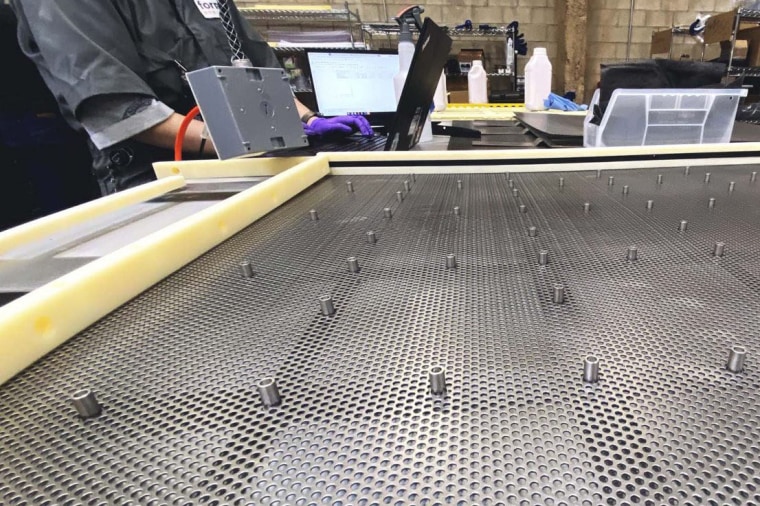

The batteries discharge energy from pellets of iron as they “rust” or oxidize in oxygen from the air; the reverse chemical process — effectively “de-rusting” — then uses electric current to convert the rust back into pure iron. Each iron-air battery is about the size of a dishwasher, and thousands of such batteries could be placed together in a very large building to store megawatts of renewable electricity on the grid until it’s needed.

Form Energy is far from the only company trying to solve this problem. Renewable wind and solar energy now make up about 10 percent of the electricity used in the United States. But sometimes the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow, and today’s power grid doesn’t have a lot of storage. Fossil fuels like gas and coal, which environmentalists hope to eliminate as energy sources, can supply power to the grid in just a few seconds and don’t have such shortcomings; it’s hoped that grid-scale storage can replace at least some of that “on-demand” need for electricity.

“Cost-effective, durable and reliable energy storage opens up whole new areas of possibility for grid decarbonization,” said Costa Samaras, an associate professor of environmental engineering at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh who studies efforts to create a power grid with effectively no carbon emissions. “It reduces the stress on the grid during peak times, and it stores renewable energy in the times where you have a lot of it to the times where you don’t.”

That might be from minute to minute — when a cloud passes in front of the sun, for instance — or at different hours of the day, such as when there’s no wind during the times of peak demand for electricity in the afternoons and evenings. Short-term demands can now be met relatively cheaply thanks to grid-scale installations of lithium-ion batteries such as the 250-megawatt Gateway Energy Storage facility in California.

Although the costs of large “Li-ion” installations have dramatically dropped in recent years, they become expensive when they are designed to last more than 10 hours or so. Renewable energy advocates have pushed for investment in new technologies to enable renewables for the demands of a modern power grid.

Although the chemistry behind iron-air batteries isn’t new, they’ve been overlooked because they are too heavy to be portable. Form Energy said its proprietary technology for extracting oxygen from the air through a membrane makes the chemistry feasible for stationary storage, and at a much lower cost than equivalent lithium-ion facilities. They’re also safe and made from abundant ingredients — unlike lithium-ion batteries that need plentiful supplies of hard-to-get lithium.

Form Energy said its iron-air battery facilities will cost about $20 per kilowatt-hour, falling to about $10 per kilowatt-hour by the end of the decade. By way of comparison, grid-scale lithium-ion facilities cost between $250 and $300 per kilowatt-hour, Jaramillo said. The company is now working with a utility in Minnesota on a 1-megawatt storage facility that will be completed in about two years, but after 2025, “we will scale pretty quickly into the tens and subsequently hundreds of megawatts, which is the sort of scale you have to be to really make a difference on the grid,” he said.

Iron-air batteries are just one of many ideas for grid-scale storage, according to Chris Knittel, a professor of applied economics who directs the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research.

Others include using spare electricity to pump compressed air into underground salt caverns, then to power turbines when the electricity is needed, or using the electricity to make ammonia, which can be stored and then used in fuel cells to extract the energy.

“There are even ideas of using electricity when it’s cheap to drive a train up a hill, park it and then to use it to generate electricity as it comes down,” he said.

Some areas are blessed with hydroelectric schemes that can store electricity as “pumped hydro” by pumping water uphill into a reservoir, for example, and using it later to drive turbines, but many regions will need large-scale battery storage to support renewable electricity sources like solar and wind, he said.

Existing methods of generating electricity at short notice, mainly by burning fossil fuels like natural gas, have so far managed to smooth out the intermittent supplies from renewables, but not for much longer.

“We’re all trying to think about a system where there is no natural gas,” Knittel said. “In that world, batteries are going to become important, or necessary.”