At the end of May, The Virginian-Pilot, a daily newspaper in Norfork, Virginia, ran a legal notice in its classified section warning readers that it might become illegal to sell or lend a particular book.

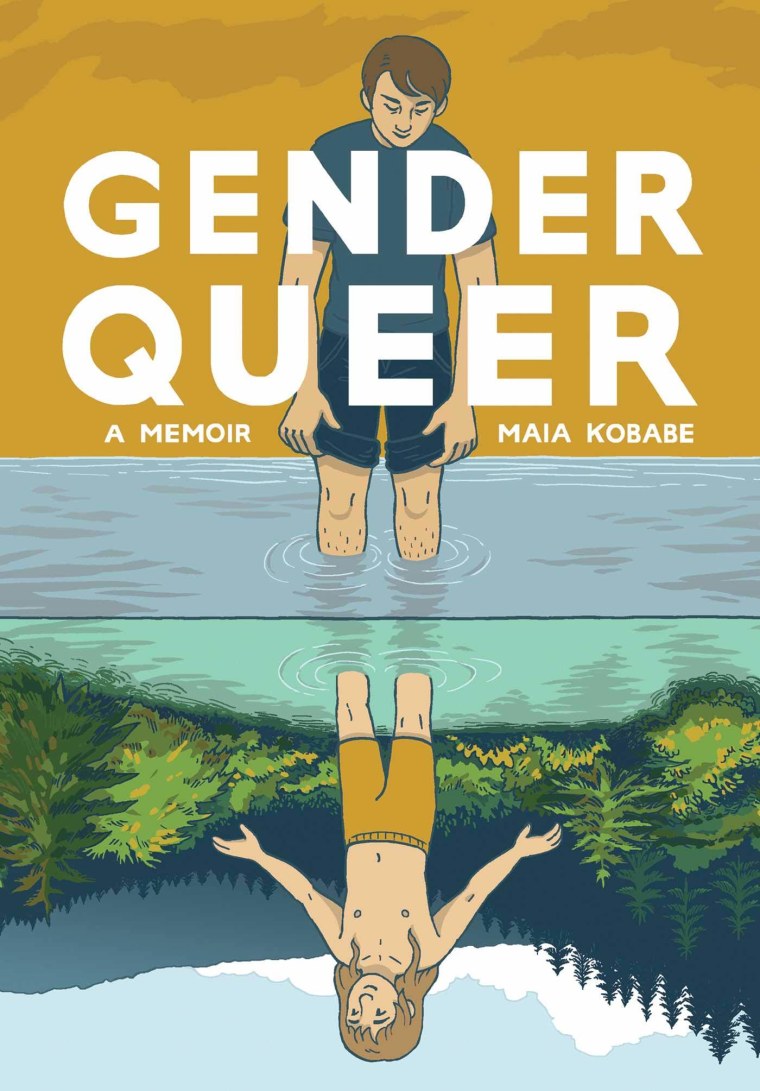

Maia Kobabe’s comics memoir, “Gender Queer,” had been the subject of an obscenity lawsuit in Virginia Beach, and the judge in the case found probable cause to believe that the book was “obscene for unrestricted viewing by minors.”

The affecting story of a young person, assigned female at birth and struggling to define “eir” identity (Kobabe uses e/er/eir neopronouns), “Gender Queer” has won or been nominated for several awards. But its fate in Virginia will be decided by a retired judge, Pamela Baskervill, at the end of August.

This is the latest salvo in arguably a years-long war on queer cartoonists and authors waged by Republicans eager to shore up support by persecuting and slandering minorities. The complainant in Virginia is Tommy Altman, a Republican candidate for the state’s 2nd Congressional District, who placed third in a four-way primary this June. But it is, frankly, a bit shocking that the case will be heard at all: Obscene for unrestricted viewing by minors” is not a legal category in any statute, state or federal.

Just before Altman filed his suit in May, the Virginia Beach school board voted to have “Gender Queer” removed from libraries for being “pervasively vulgar.” It is the most-challenged book of 2021, according to the American Library Association (ALA), knocking Alex Gino’s “George,” a novel about being a transgender child, off the list for the first time in the five years since its publication. Altman’s case is absurd, but that doesn’t mean he won’t ultimately prevail, and the threat of legal action is often more than enough to prevent retailers from carrying a book anyway.

The ALA’s lists of most-challenged books across the decades are enlightening: They display a growing bigotry toward not just real queer people, but queer characters who might help children discover their own identity. And queer comics — with their unavoidable images of marginalized people — are regularly targeted, often by conservative influencers and even lawmakers. (Arizona Senate candidate Blake Masters recently tweeted a deceptively redacted illustration from “Gender Queer” as supposed evidence of its depravity.) This backlash is perhaps hardest on young cartoonists like Kobabe, whose reputations can be damaged in ways that seasoned pros like Art Spiegelman’s can’t. This is a significant shift: During the previous decade, parents were much more concerned with the Harry Potter and “His Dark Materials” fantasy novels, or the antiwar message of “Slaughterhouse-Five.”

That graphic novel storytelling is popular with LGBTQ authors shouldn’t be surprising. Since conservative politicians used comics as a scapegoat for juvenile delinquency in the 1950s, the medium has arguably been more hospitable to social outcasts than its more popular cousins, and LGBT creators have had a constant presence in its pages since the 1980s. The popularity of manga has also helped, influencing generations of American artists and introducing them to LGBTQ characters. Comics, frankly, are often just gayer than literary fiction or sci-fi.

At the same time, no other sector of the book world is growing as consistently: In the U.S., graphic novel sales were up 65% in 2021, according to the market research firm the NPD Group, and that was actually down from the previous year, when sales fully doubled.

Comics’ growing cultural cachet also correlates with greater cultural visibility for gay people — an all-time high of 7.1% of Americans are comfortable identifying as a sexual minority, according to a Gallup poll in February — and that broad tolerance, especially among young people, seems to be fueling a backlash. And who better for conservatives to blame than degeneracy in popular culture.

Kobabe’s book, for example, has morphed into a very useful target for GOP propaganda. “Gender Queer” appears regularly on lists of books that right-wing legislators find offensive, notably “Krause’s List,” a spreadsheet of books Texas state Rep. Matt Krause said should be banned from schools and libraries. (Krause at one time contemplated running against embattled Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton.)

The furor over Krause’s list reached a fever pitch last November amid the right wing’s then-obsession with “critical race theory.” Krause targeted plenty of authors of color, especially Black authors. But overwhelmingly, the books he wanted banned were about LGBTQ people — almost exactly two-thirds of the books his list dealt with LGBTQ characters or were by openly LGBTQ authors, according to an analysis of the 850 books by BookRiot.

For anyone who remembers the gay rights movement in the 1990s, this kind of slander should sound familiar.

In Massachusetts, meanwhile, “Gender Queer” has been pilloried by the far-right politician Rayla Campbell, the presumptive Republican nominee for the state’s third-highest office. But Campbell’s campaign has not done much more than denigrate gay and trans people, regularly insinuating that sexual minorities try to use the school system to take advantage of children. For anyone who remembers the gay rights movement in the 1990s, this kind of slander should sound familiar.

Barring some dark magic, Campbell will lose in the general election to William F. Galvin, who has been the secretary of the commonwealth since 1995. But huge damage has already been done by the broader censorious focus on “Gender Queer” and other books about queer characters.

This of course is backwards, cruel and dystopian. Queer comics should be celebrated, especially when they help young people learn to accept themselves. Kobabe’s memoir will go before a court of law at the end of August, but we ought to rejoice over it now. More than just a memoir of self-discovery, it stands in gratifying contrast to Kobabe’s predecessors, which often featured characters preoccupied with ostracization and loneliness.

In “Gender Queer,” Kobabe implies that others can — and should — be free to discover their own version of freedom. Altman, Campbell, Krause and their ilk would like to bring back a world where that’s not possible. But we’ve read that story, and it’s over now.