Sankofa. It’s a word in the Ghanaian Adinkra language that means “We must remember our past in order to protect our future.”

This year I celebrate my 60th year on this planet, and I am thinking often of the responsibility of remembering. I’ve lived with HIV for most of my life. I never expected to make it to 30, much less 60. I am of a generation that lost scores of friends and loved ones through this disease, and I was given a death sentence on more than one occasion.

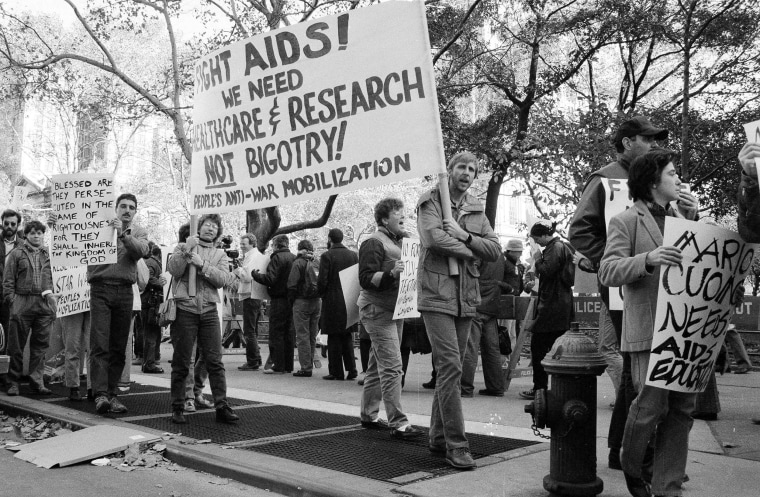

Eventually I came to understand that the only way to save my life and the lives of those I love was to fight—to fight the disease, to fight all the “isms”, to fight the stigma, to fight an uncaring government, to fight an ignorant public, to fight an inadequate health care system, and to fight my own fears of inadequacy.

“We must remember our past in order to protect our future.”

We’re at a decisive moment in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The remarkable advances that we’ve made in the past decade have given us diagnostic, surveillance, treatment and prevention tools that we never could have imagined. But every year, 50,000 Americans contract the virus—nearly half of them black—and thousands still die from the disease.

As I make my 60th trip around the sun, I want to use my past as a motivational tool to protect our future. As I remember the most difficult days of the epidemic and reflect on how far we’ve come, I urge everyone to also understand how close we are to turning the tide—for good.

My Journey

I came out in 1980. I was engaged to be married to my college sweetheart, and then I met a man named Chris Brownlie. Everything changed. I would call it love at first sight, if there were such a thing. The week after I met him, I gave my mother the book Loving Someone Gay. Within a month I had broken up with my fiancee, and Chris and I moved in together.

Understanding that I was a gay man, discovering my true self and falling deeply in love was euphoric. But also short-lived. In 1981 my doctor discovered that I had swollen lymph nodes. He had recently read an article about gay men with this symptom and a new disease then called GRID, or gay-related immune deficiency. That was my introduction to HIV/AIDS.

By 1984 I realized that my friends were dying—it wasn’t just people I had heard about or read about; it was people I knew and loved. Before they actually died, they would disappear. We might be having dinner or out dancing, and then a few weeks later their apartment would be empty and they’d just be gone. That usually meant they’d gone back “home” to die.

I was just 26 years old.

By 1986 Chris was very sick, and we assumed that I had contracted the virus as well. My diagnosis was confirmed in 1987. At that point, Chris and I and most of our friends were living day by day, sometimes minute by minute, trying not to die. We lived in a constant state of triage: If we don’t die today, then we’ll deal with the pneumocystis attack that’s preventing us from breathing. If we’re alive the day after, we can cope with the fact that we may be going blind.

As I make my 60th trip around the sun, I want to use my past as a motivational tool to protect our future.

In 1989 Chris died in my arms. I had neither the time nor the desire to process my grief. Things were so catastrophic that I felt like if I let myself understand the depth of what was going on, I would never, ever come out of it.

For me, the solution was to work.

In 1990 I became the AIDS coordinator for the city of L.A and then the director of policy and planning for AIDS Project Los Angeles. My goal was to end each day as exhausted as possible, so when I collapsed into bed I would be too tired to think or dream. This went on until 1996.

In the beginning, we didn’t think the plague would go on for so long—maybe a year, maybe a few years. We thought, “The government will fix this. They aren’t going to just let us die.” But eventually we all realized, “No, they are going to let us die; they aren’t sending the boats back for us. Nobody was going to save us, but us! So, we kept fighting.”

Eventually, my body said “enough is enough!” In 1996 I contracted pneumocystis pneumonia and Cryptococcus Meningitis at the same time. My doctors gave me less than 24 hours to live. I was very weak and could barely breathe. I was in the intensive care unit at Kaiser Permanente Hospital, a tube down my throat. My blood count was dangerously low, and my T cells had dropped to nearly 0.

But then something miraculous happened. The doctors started me on protease inhibitors, the new drug “cocktail” that had been approved a few months earlier for treating AIDS. That medication saved my life—and went on to make the disease “manageable,” instead of deadly, for millions of others.

But not for the vast majority of black people. For all the talk about the epidemic being over, for most Black folks it was as if the cocktails didn’t exist. Yes, there were improvements, but the degree of change in black communities relative to white communities was striking and shocking.

In fact, in 1996—the year AIDS “ended”—Blacks accounted for a larger proportion of AIDS cases (41 percent) than whites for the first time since the start of the epidemic.

Making a Difference

I founded the Black AIDS Institute in 1999 because I was terrified that black communities were being left behind. We were not getting information about prevention and treatment, and no one was focusing on the unique determinants of health that impact our communities. I wanted to create a space that looked at the disease through an unapologetically black lens and where the focus was squarely on us—where we mattered.

And we have made progress. Black communities have come together to address HIV/AIDS in our communities. We are not where we need to be to end the epidemic in our communities, but we are a very long way from where we were in the early days.

Whereas in the first 15 years, there was little effort to proactively confront the disease in black communities at large, today almost all of the major black civil rights organizations have an AIDS plan and/or a national HIV/AIDS coordinator.

We have the power to end the AIDS epidemic. The tragedy will be if we can do it, but don’t.

Politicians, media organizations, celebrities and churches have stepped up to talk about the disease and how to fight it. And more individuals are taking responsibility for their own health through testing and treatment.

But it is not over. According to new government data, if current rates persist, 1 out of every 2 black gay and bisexual men will become infected with HIV over their lifetimes.

And the disease has taken hold in the South, which has the least resources but the highest disease burden and the highest level of stigma.

Where to Go From Here

Still, we can protect our future. Ending HIV may not be easy, but it is simple:

1. Know your status. That should be the starting point for everyone.

2. Provide treatment for people who are HIV positive. Treatment works two ways: First, it helps people living with HIV/AIDS live longer healthy lives. Second, treatment functions as prevention: Treatment as Prevention reduces HIV transmission by over 90%.

3. Make sure that those at high risk of HIV infection have the prevention tools they need. These include condoms, abstinence for those for whom it makes sense and biomedical interventions like Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). PrEP reduces acquisition of HIV by over 90%.

We have the power to end the AIDS epidemic. The tragedy will be if we can do it, but don’t.

As told to Linda Villarosa, who runs the journalism program at City College in Harlem and writes frequently about health and social issues. You can follow her on Twitter.

In honor of Wilson’s birthday, there will be a 60th Birthday Jubilee and Roast to benefit the Black AIDS Institute on Saturday, April 23rd in Los Angeles.