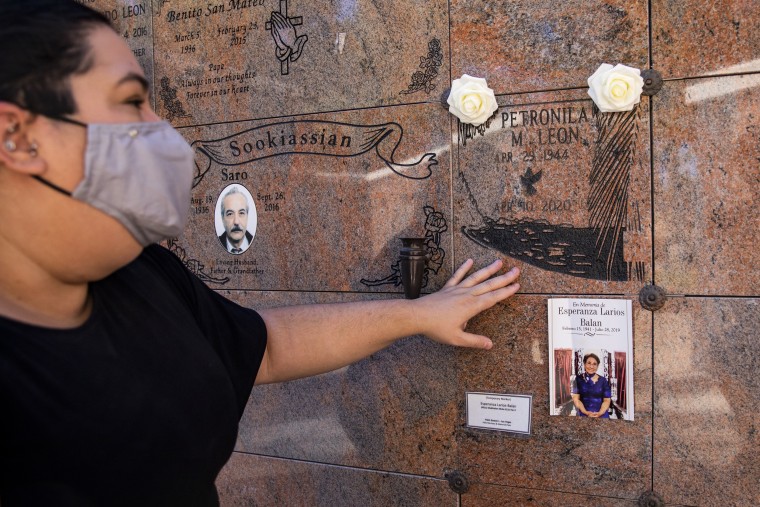

LAS VEGAS — Kenia León kneeled and placed a white silk rose through a crevice at the top of her mother’s mausoleum marker on a mid-October afternoon. She paused for a few seconds and moved it slightly to the left.

“I can hear her voice in my head yelling at me to make sure they are even,” Kenia, 39, said, as she smiled and wiped a tear from beneath her round, black sunglasses.

It was just over six months since her 75-year-old mother, Petronila Maria León, had died of Covid-19.

“She should still be here,” Kenia said, brushing her hand against the engraving on the mausoleum marker. She and her brother had chosen an island scene to be engraved on the granite niche. Born and raised in Cuba, their mother had always loved the ocean.

Kenia turned her head and looked around the cemetery. She wondered how many others laid to rest there had died from the coronavirus. On April 10, the day her mother died, the toll in Nevada had reached 120. Since then, it had grown to nearly 1,700. She wondered how many families, like hers, were still feeling the virus’s impact on their health, livelihoods and futures.

Kenia snipped another silk flower for her mother’s mausoleum marker. The funeral home had not yet installed a vase as her family had requested.

She sighed. It was another piece that remained unfinished.

The pandemic hits

If Petronila, who went by Mery to her friends and family, did not feel well in the week before she went to a doctor’s appointment the morning of March 24, she had not told her three children. She rarely showed weakness, physical or emotional.

Before retiring, she worked at a school cafeteria for nearly 20 years and rarely missed a day on the job. Her children recalled that when she broke her foot in the late 1980s, she still went to work on crutches. When her husband of 51 years, Jose León, died of cancer in 2016, she promptly packed up his belongings, tossing nearly everything. She pushed through hardship by looking to the future.

That morning, her middle child, Rodolfo León, 47, felt nervous as he drove his mother to the doctor. She was scheduled to receive an iron infusion after recent lab tests showed she was anemic — and as the pandemic spread, Rodolfo, who goes by Roy, wanted to make sure his mother was healthy.

Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak had shut down schools on March 15. Two days later, Roy, an elementary school physical education teacher, and his fiancé, Reba Mathai, 30, a second-grade teacher, who both lived with Mery, came down with stuffy heads and lost their sense of taste, Covid-19 symptoms. Kenia, who also lived in the home, felt coronavirus symptoms a few days later, with a cough, fever and chest pains. Mery had no outward symptoms, except mentioning a mild stomachache.

For more of NBC News' in-depth reporting, download the NBC News app

The family began taking precautions: isolating from one another and wearing gloves and masks everywhere they went, even inside the house. They used disinfectant frequently.

Covid-19 tests were still in short supply in Nevada, and Roy and Kenia were still waiting for their results. Roy hoped that their symptoms were nothing to worry about.

Mery had only been with the doctor for 15 minutes when he came into the waiting room and told Roy they were taking his mother to the hospital by ambulance. She seemed weak, her heart rate was high and he felt she needed immediate medical attention.

Roy grabbed his mother’s walker, her purse and coat and ran outside as paramedics placed her in an ambulance.

“I’ve got your stuff and I’ll meet you there,” he yelled.

But when he got to the hospital, the security guards would not let him inside; no visitors were allowed.

Roy broke down. Unable to drive, he called his sister to pick him up.

It was the last time he saw his mother.

Within the next week, all of the family had been tested and received their Covid-19 results: positive.

Waiting without sleep

Kenia remembered coughing and sitting upright in her bed. It was March 31, several days since she had tested positive for Covid-19. Her cough had gotten worse, especially at night. She had a 102-degree fever that didn’t seem to break. Just walking around left her short of breath.

A psychotherapist at a private behavioral health hospital in Las Vegas, Kenia had been out sick from work since she began feeling symptoms.

Her physical condition coupled with the anxiety she felt about her mother made it hard to sleep. Nurses and doctors at Spring Valley Hospital called each day with updates: Her mother’s blood was not clotting, or her kidneys were failing. Still, they said Mery appeared to be fighting back as hard as she could.

Kenia mostly stayed in bed. But she could feel a shift in the home.

The salsa music her mother danced to while she cleaned wasn’t blaring through every room. The smell of garlic, onions and cumin wasn’t wafting through the house from her cooking ropa vieja, a Cuban stew with shredded beef and tomato sauce.

That night, Kenia tried to sleep, but she felt restless. Around 2 a.m., she heard her cellphone ring. The number belonged to the hospital. She picked up, praying it was not bad news, and heard her mother’s voice on the line.

“I’m hungry,” her mother told her in Spanish. “The food here is bad.”

Confused, Kenia asked how she was doing or if she needed someone to bring her something.

“I want a hot dog,” Mery said in English. Then she hung up.

Kenia immediately tried to call her mother back, but she did not pick up. She called the nurses’ desk and asked if her mother was OK. They called back and said that her mother’s condition had not changed.

The next day, doctors put Mery on a ventilator.

About a week later, she died.

That day, Kenia called the hospital where she worked to ask about bereavement leave. They told her they were sorry about her mother’s death.

Next, they told her they were downsizing. She was being laid off.

Last wishes

A package arrived at the León family home nearly two weeks after Mery died. It was Reba’s wedding dress.

Roy and Reba had gotten engaged in 2019 after dating for four years. Roy left his school early that day and surprised Reba with a proposal at her school. The couple had scheduled their wedding for June 6, but when the pandemic hit in March, they canceled it.

Still, when her dress arrived, Reba tried it on. As she looked in the mirror, she thought of Mery. When Reba had been searching for wedding dresses, indecisive, it was Mery who helped her make her final choice, assuring her the lace dress would look gorgeous.

Reba thought about how, less than a week before her mother-in-law-to-be was hospitalized, Mery had taught her how to make Cuban hamburgers. She wanted Reba to “know how to cook for her son.”

The day before doctors intubated her, Mery had called Roy and asked to speak with Reba. Mery told her to take care of Roy, to make sure he never felt guilty about any past arguments mother and son may have had. Mery also said she was sorry that Reba had gotten Covid-19 while staying at their home.

“No, that’s not your fault,” Reba remembered telling her. “Don’t feel bad.”

She changed out of the dress, putting it away, unsure when she’d wear it next.

The death certificate

On April 24, a month after her mother was hospitalized, Kenia sat in her car in the parking lot of Palm Eastern Mortuary, gripping her mother’s death certificate.

The last few weeks had been a blur of activity: She had filed for unemployment. She, Roy and Reba had been retested for Covid-19 — the results were negative. Now they were planning their mother’s funeral.

“Cardiopulmonary arrest due to or as a consequence of septic shock due to or as a consequence of pneumonia due to or as a consequence of Sars-COV 2/ COVID-19,” Mery’s death certificate listed as the cause of death. An additional line with other significant conditions listed “multisystem organ failure.”

It was the first time Kenia realized how much her mother had gone through. Seeing it all together, one right after the other, was too much.

Kenia began to weep, wondering how much her mother had suffered.

Saying goodbye

Five days later, on April 29, Kenia, Roy and Reba celebrated what would have been Mery’s 76th birthday. Their mother always marked birthdays, no matter how old they were, by decorating the dining room, getting a cake and making their favorite dishes.

That day, they hung up a banner, pulled out “Happy Birthday” paper plates and hung blue and white balloons. They ordered bistec empanizado, a Cuban version of chicken-fried steak, and ropa vieja from a local Cuban restaurant. A family friend baked a chocolate cake, Mery’s favorite, and dropped it off.

After dinner and cake, Kenia lit a candle and the three of them sat in the living room watching “The Last Word with Lawrence O'Donnell,” Mery’s favorite show. They laughed, remembering how O’Donnell was her biggest crush (though Jason Momoa came in as a close second; she saw “Aquaman” in the theater eight times).

The next week, on May 8, they stood outside a community mausoleum at the cemetery for their mother’s funeral services. Nevada had eased some pandemic restrictions and they were able to gather in person: Kenia, Roy, Reba, Mery’s eldest son, his wife and their two children, and Roy’s best friend.

Mery’s children had her cremated, though they were not sure if that’s what she wanted. Mery, who’d grown up under the Santeria faith — an Afro-Caribbean religion with many Catholic elements — hadn’t had many conversations with her children about her funeral.

Burial services were prohibited because of the pandemic and would have delayed putting her body to rest, so the children reluctantly settled on cremation. Mery had bought a long, blue velvet dress with an ornate gold collar years earlier, and told her children she wanted to wear it after she died. The funeral home agreed to place the dress on top of her body when they cremated her.

The service lasted about 20 minutes. A priest said a prayer. Mery’s family placed the blue urn they’d chosen for her ashes inside the mausoleum niche, two over and one down from their father’s. Alongside the urn, they placed fresh white roses.

A funeral home employee then drilled a metal sheet over the niche — the granite marker was still being engraved.

Kenia listened to the loud buzz of the drill against the metal. She wondered how many lives could have been saved, including her mother’s, if the government had called for a shutdown earlier.

The next day, phase one of Sisolak’s plan to reopen the state began.

Voting, alone

Because of the pandemic, Nevada’s June primary was held almost entirely by mail-in ballots. So, on an afternoon in late May, Kenia sat at her kitchen table and filled hers out. Covid-19 had taken a disproportionate toll on Latinos in Nevada, and she felt it was even more important for their voices to be heard in this election.

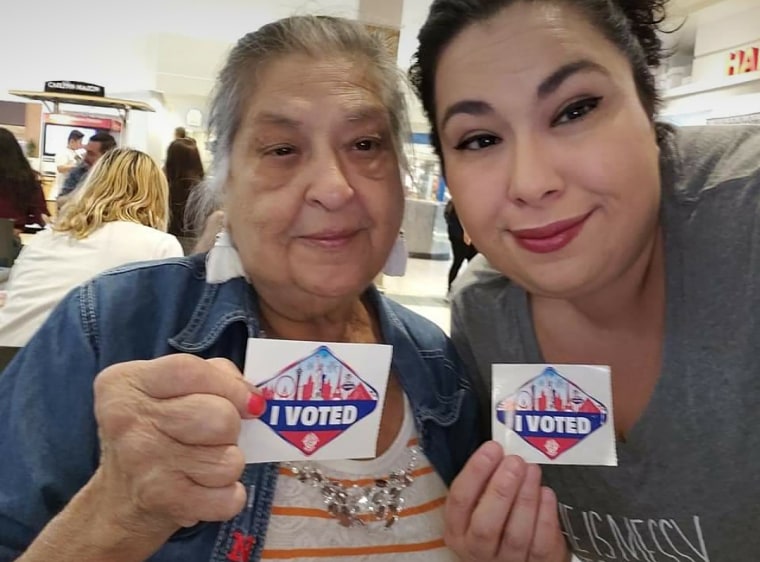

She knew if her mother were still alive, she would have been right next to her, chatting about casting her vote.

Voting was important to Mery. Since she became a U.S. citizen in 1998, Mery never missed an election. She fled Communist-ruled Cuba in 1963, and she viewed voting as an expression of her voice in the political system. Though many Cubans tended to vote for conservatives, Mery leaned left, telling her children it was the best way to prevent authoritarianism.

After she finished with her own ballot that afternoon, Kenia began filling out Clark County’s “deceased voter report,” a form used to take those who have died off the voter rolls. Slowly, she wrote in her mother’s information.

Kenia then drove to the election office to drop off her ballot along with the form for her mother and a copy of her death certificate.

It was the first time in 21 years that she had gone to vote without her mother.

Lingering effects

Kenia, Roy and Reba continued to feel the virus’s lingering effects well into the summer, making them part of a growing group known as “long-haulers.”

Roy, who had cancer in 2016 but had been in remission following radiation treatment, suffered from gastrointestinal issues. Reba and Kenia experienced heart palpitations, hair loss and fatigue. On many days, Kenia still had so much trouble breathing, it was exhausting to hold a conversation.

Kenia had been too ill to look for a new job and relied on unemployment insurance and her savings to help make the household’s bills and her car payment. She had applied to Nevada’s Affordable Care Act plan but had no health insurance in the meantime.

At a check-up appointment over the summer, Reba recalled the doctor telling her she had been lucky because her symptoms were mild. She thought of Mery’s death. She thought of Kenia, who sometimes became exhausted just from taking a shower.

No, she told him, she was not lucky, because her family was still suffering.

Later in the summer, as the Clark County school district began to discuss potentially holding in-person classes, Reba wrote a letter to the school board. She explained that if the district resumed classroom instruction, she would consider not coming back. Her family had already suffered one loss and she would not put them in harm’s way.

Changed plans

School resumed virtually in August. While Reba and Roy felt more comfortable distance-teaching, it was still a struggle.

Reba tried to keep her some semblance of normalcy for her 14 second graders, starting the day with a morning dance and ending it by asking the class about their favorite activity. Roy adjusted to teaching health instead of physical education.

Both still struggle to keep their energy up, a lingering effect of Covid-19.

The couple decided to wed in November. Rather than the 250-person event they had planned, the ceremony and reception at a northern California winery will include only their immediate families.

They will bring a picture of Mery to the ceremony.

Kenia was accepted into the state’s Affordable Care Act plan, but because of the program’s red tape, she wasn’t able to see a heart specialist until early October. She now wears a monitor on her chest, while she awaits more tests and a diagnosis.

Her unemployment runs out in three weeks. But Kenia, emotionally and mentally exhausted, is not sure she can return to being a therapist.

Later that October afternoon, after she left the cemetery, she called the funeral home, asking why the vase had not yet been placed on her mother’s mausoleum marker. They assured Kenia they would try to remedy it as soon as possible.

She’s not sure how soon that will happen.