FULTONDALE, Ala. — As a tornado with winds of up to 150 mph tore through this small Alabama city last year, 14-year-old Elliott Arizaga-Hernandez dashed upstairs to grab his lantern, a birthday gift, in case the lights went out. He sprinted back down to the basement and joined his parents and his four brothers, huddling together as the windows upstairs shattered.

Elliott’s older brother Christopher later recalled that they heard a roar like a train engine. “Get down!” Christopher screamed. A brick wall in the basement collapsed. Their mother, Saraid Hernandez, grabbed Elliott moments before the ceiling caved in.

“Mommy,” Elliott cried as a beam fell, pinning Saraid’s arm with Elliott below it.

She knew then that she was badly hurt, she later told Christopher. But she was more worried about Elliott, her second-youngest son.

“Pray,” she told him in Spanish. “Don’t worry, just pray.”

The tornado that cut a 10-mile path through Jefferson County, Alabama, on Jan. 25, 2021, destroyed 86 homes and severely damaged 45 more, devastating Fultondale, a suburb north of Birmingham with a population of nearly 10,000. The winds were strong enough to flip storage containers and a mobile home.

“Our town got demolished,” Mayor Larry Holcomb said afterward. “I mean, completely destroyed.”

As the magnitude of the losses became clear, Holcomb and local emergency management officials pleaded for help from the federal government — up to the White House. The Federal Emergency Management Agency estimated that the cost to support those without insurance in finding temporary shelter and beginning to rebuild their homes would top $1.8 million.

But the federal government denied Jefferson County’s request for help, saying the tornado did not cause enough damage to require FEMA’s help. Now, more than a year later, leveled houses are surrounded by debris. After FEMA’s denial, Holcomb pinned his hopes on the state, but was frustrated to learn that there is no publicly funded aid available in Alabama for those who cannot afford to rebuild.

“They don’t offer anything,” he said.

FEMA’s Individual Assistance Program spends hundreds of millions of dollars each year helping uninsured residents recover after severe storms. If the White House approves a state’s request for aid — generally based on a recommendation from FEMA — eligible families can receive up to $75,800 for expenses including home repairs, temporary hotel stays, hospital bills and funeral costs. For the recipients, these funds can mean the difference between rebuilding a longtime home and becoming homeless.

But this critical aid is out of reach for many of the nation’s disaster survivors, including some of the most financially vulnerable, an NBC News analysis found.

From fall 2018 to fall 2021, the federal government turned down nearly 40 percent of states’ requests for FEMA’s Individual Assistance Program, totaling 33 denials, according to an examination of agency records. The rejections followed disasters including wildfires, flash floods, tornadoes and mudslides. FEMA estimated that it would have cost $107.5 million to fulfill these denied requests — or less than half of what the agency approved to support New Jersey residents after Hurricane Ida.

Often, these were disasters with highly concentrated damage — dozens of homes destroyed in a handful of counties, rather than widespread destruction across a state. FEMA’s program generally prioritizes aid for major catastrophes and those in densely populated areas; the agency often considers these other disasters too small to require federal assistance, saying that state and local governments should be able to help instead.

However, the NBC News analysis found that many of FEMA’s rejections occurred in communities where economic hardships left disaster survivors with few other paths to recovery: Nearly all of the communities that were denied federal aid had poverty rates higher than the national average, while in two-thirds of these communities, less than half of the affected residents had insurance.

Alabama, one of the poorest states, was turned down the most often in this three-year period, after requesting aid for a 2018 hurricane, winter storms in 2019, and the 2021 tornado in which the Arizaga family’s home was destroyed.

Alabama is also one of at least 39 states that lack a publicly funded state aid program designed to help disaster survivors rebuild their homes, according to a 2020 survey by the National Emergency Management Association. Without federal or state assistance, struggling residents in these states are often left to rely on loans or charity — an imperfect safety net, according to elected officials, emergency managers, community advocates and disaster recovery experts.

While FEMA may not be able to help every community that requests aid — and while states bear some responsibility for mitigating the impact of disasters — the federal government should still step up to help vulnerable people in need, said Carlos Martín, a researcher at the Brookings Institution who studies the financial fallout of disasters.

“There is a role for the federal government to come in and help [when] the state hasn’t,” he said.

Martín believes that FEMA should have a separate approval process for aid to underresourced communities, to ensure that they are prioritized.

Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., has been fighting to change this process for a decade, ever since FEMA denied aid to Illinois after a 2012 tornado in Harrisburg destroyed or damaged more than 200 homes and left eight people dead. After that, he said, he learned not to promise his constituents that he would bring home disaster relief from Washington.

“I stopped saying those things because I didn’t want to create false hope,” he said in a recent interview. “It’s so rare that there’s assistance coming back from Washington.”

FEMA considers a range of factors in deciding which disasters deserve aid under its Individual Assistance Program, primarily focusing on the state’s economy and the share of damaged or destroyed homes that were uninsured. (FEMA also has a separate Public Assistance Program, which helps local governments rebuild infrastructure after disasters and has a more transparent threshold for which communities receive aid, based on the amount of damage per capita.)

Durbin has pushed for legislation that would require FEMA’s Individual Assistance Program to place a clearer emphasis on local economic circumstances, including by considering the community’s median income. But his bill hasn’t advanced.

In response to NBC News’ analysis, FEMA released a statement saying that it has been working to make its Individual Assistance Program more equitable and to “meet people where they are to identify and remove barriers to our programs.”

“We’re also leaving no stone unturned when it comes to helping socially vulnerable communities and survivors,” the statement continued, “and efforts that require statutory or regulatory changes are also on the table. The bottom line is, we’re looking at this from all angles and will do all we can to support vulnerable communities and survivors through our individual assistance program.”

FEMA declined to provide details about any proposed policy changes.

Academics have amassed a growing body of research showing racial and economic disparities in FEMA’s disaster relief programs.

On his first day in office, President Joe Biden issued an executive order instructing all agencies to assess whether — and to what extent — their programs “perpetuate systemic barriers to opportunities and benefits for people of color and other underserved groups.”

The White House, which has final signoff on disaster declarations and aid based on a recommendation from FEMA, declined to comment beyond FEMA’s statement. Biden nominated a new FEMA administrator, who was confirmed last April, but the Individual Assistance Program’s criteria have not changed.

The issue is growing more urgent as climate change fuels stronger storms, exacting an uneven toll because of inequities in where and how homes are built. That makes it even more important to address how the government helps those who lose everything, experts and advocates say.

“If we continue to get these kinds of disparities in terms of declarations and the flow of funding, we’ll find more and more communities of color and poor communities further marginalized, underprotected,” said Robert Bullard, director of an environmental justice resource center at Texas Southern University. “And we’ll be placing them at greater risk.”

The house on Oak Street

For four years before the tornado hit Fultondale, the Arizaga family had lived in the little white house on Oak Street. The two-bedroom bungalow was a tight fit for the family of seven, but it sat atop a hill, giving Saraid a view from the kitchen window of the youngest boys as they walked home from the bus stop.

After Oscar Arizaga Sr. was in a serious car accident in 2019, the family remodeled the bathroom to include a walk-in shower. They were renting the home, but had signed a contract that they hoped would enable them to buy it someday.

The tornado destroyed the house within seconds, splintering beams supporting the floor above the basement, the family members later recalled. After the winds died down, Christopher, 20, called 911. Then he helped Brandon, 16, and his youngest brother, Eddie, 7, climb over the collapsed brick wall in the basement. But Elliott remained trapped inside, along with his parents and his oldest brother, Oscar Jr.

Christopher tried to pull them to safety, but there was debris everywhere. He heard his mother singing from below: “Dios, grande es tu amor…” “God, great is your love.”

Oscar Jr., 23, who was pinned down by plywood in the dark basement, called out to Elliott to see if he was OK.

“He’s OK,” Saraid told him. “Stop calling his name.”

Oscar Jr. heard his father groaning from beneath a beam. Oscar Sr., 45, had spent much of the previous year unable to work, recovering from the car accident. He had just returned to his job building coils for large industrial motors several weeks earlier. His son worried: What if he has been injured again?

Emergency responders arrived and started freeing Oscar Jr. Before they helped him outside, his mother told him she didn’t know if she would survive. She told him to be strong for his younger siblings. Then she shared: “Your brother didn’t make it.”

Oscar Jr. didn’t believe her. She’s not thinking straight, he thought.

After rescue workers helped him outside, he saw that the street looked like “the apocalypse,” he said, with neighbors screaming for help and sirens blaring. Emergency responders freed his parents and brought them to waiting ambulances.

But when the emergency crew reached Elliott, they found that he had been crushed by a falling floor joist and an air conditioning unit after the home’s first floor collapsed. They wrapped his body in a sheet and carried him outside to await the coroner.

Oscar Jr. knelt on the road and cried. “In the Arizaga family, there are five brothers, not four,” he yelled. “There are supposed to be five.”

Help denied

In the days after Elliott’s death, the Arizaga family confronted grief and a new reality. Like dozens of other families in Fultondale, their home was a complete loss.

More than one-third of the Jefferson County residents whose homes were damaged had no insurance, according to federal estimates, which listed the poverty rate at 16 percent As they waited to see if the federal government would send aid, many residents turned to nearby churches and their neighbors and relatives for help. City officials collected donations to pay for hotel rooms, but with debris cleanup already cutting into the city’s reserve funds, there was little more local authorities could do.

The Arizaga family had no renters’ insurance and still had outstanding medical bills from Oscar Sr.’s car accident. Their cars were destroyed in the storm, smashed by falling tree branches.

Saraid was released from the hospital quickly, but Oscar Sr. needed surgery for his broken arm and was hospitalized for days.

As word of Elliott’s death spread, a fellow congregant offered the family a room in her two-bedroom home so they wouldn’t be homeless. An anonymous donor paid for Elliott’s funeral.

On Feb. 9, 2021, the family buried Elliott after a sermon that brought Christopher some solace, particularly the part in which the pastor said they’d see Elliott again, in heaven.

Holcomb, the mayor, came to pay his respects and left the family a business card, saying to call if they needed anything.

“They literally lost everything they had, including their child,” he said recently. “I can’t imagine the stress, or the pain that they went through.”

Two days after the funeral, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey, a Republican, requested a major disaster declaration from the Biden administration to enable Fultondale residents to apply for FEMA’s Individual Assistance Program. In her request, she wrote that the state was still recovering from a hurricane and a tropical storm the previous fall and couldn’t provide the help that Fultondale needed.

“The state of Alabama has no state program available to support individual and family recovery,” Ivey wrote. “Individual and family recovery will exceed the local jurisdictions and the State’s ability to support.”

Her request was one of at least 36 FEMA received last year for individual assistance after natural disasters. Melissa Forbes, acting assistant administrator in FEMA’s Office of Recovery, said in a recent interview that the agency considers a number of factors when deciding whether to approve individual assistance, including the state’s taxable resources, the amount of damage and residents’ insurance levels.

But there is no definitive formula, which means it can be hard for local leaders to predict whether the federal government will approve aid. And FEMA does not take into account whether a state has funded its own disaster relief program to support residents — only whether the state has the financial ability to help.

Forbes acknowledged that some disasters “are sort of on the line” in terms of whether aid is needed.

“We do our best to evaluate each situation based on the information that states provide to us,” she said.

On March 17, the federal government denied Alabama’s request for aid. Forbes said the damage did not exceed the state’s ability to respond.

But the state did not offer help, either. Ivey’s office referred questions to the Alabama Emergency Management Agency. Greg Robinson, a spokesman for the agency, said that in discussions with state legislators, the agency’s officials have emphasized the importance of a program that would offer direct public assistance to people struggling to recover from disasters, but no money has been allocated.

All that was left for Fultondale residents was charity, or loans. United Way approved $139,927 in aid — less than 10 percent of what FEMA had estimated was needed.

“I don’t understand why they didn’t declare Fultondale a disaster zone,” Oscar Jr. said recently. “It was pretty messed up.”

The small city pitched in to help the Arizaga family, delivering meals and establishing GoFundMe accounts that raised tens of thousands of dollars. But Oscar Sr. was still unable to work and facing a new set of mounting medical bills.

After weeks of sharing a bedroom in their friend’s home, the Arizaga family reached out to Holcomb for help finding a place to live. He offered to let them stay in one of his rental properties for free.

‘A major source of frustration’

When FEMA turned down Alabama’s request for aid for the Fultondale tornado, Jim Coker, director of the Jefferson County Emergency Management Agency, said there was no clear answer why.

“That’s a decision that’s made above us,” he said.

Emergency managers across the country and some members of Congress have expressed frustration with this process.

In Buchanan County, Virginia, Bart Chambers, the director of emergency management, learned in January that the small Appalachian town of Hurley had lost its appeal to FEMA and would not receive individual assistance after flooding destroyed 31 homes.

“There are criteria we were supposed to meet, but I don’t know how we couldn’t have possibly met the criteria,” he said. “I get irritated because there’s no set number to it.”

In the Chalk Level neighborhood, a historically Black area in the suburbs of Atlanta, residents are still relying on volunteer groups to help them rebuild almost a year after a tornado damaged more than 130 homes, nearly a quarter of which were uninsured, after FEMA denied aid.

“They didn’t ever tell us: You fell short because of this,” said Michael Terrell, the director of emergency management for Coweta County, Georgia. “That was never relayed back to us. We just got the very generic letter.”

FEMA said in a statement that the agency works with local nonprofit groups to support disaster recovery, even in cases where individual assistance is turned down. The agency has also expanded outreach to underserved communities and worked to ensure more disaster survivors are eligible for aid once individual assistance is approved, the statement said.

In 2018, the Government Accountability Office reported that the “subjective” nature of FEMA’s decisions made it difficult for states to know when to seek help. Last October, during a U.S. House Homeland Security Committee hearing on equity in disaster response, the GAO official who oversaw that report said the lack of clarity on which communities get aid remains a problem.

“What could happen in rural Mississippi could be completely different than what happens in another part of the country, and I think this has been a major source of frustration by local officials over the years,” Chris Currie, director for homeland security and justice issues at the GAO, said during the hearing.

“They might even see a neighboring county in another state be declared for the same disaster and they weren’t,” he continued. “And they don’t know why, and they weren’t given any rationale.”

Rep. John Katko, R-N.Y., said the agency’s formulas “tend to favor big-ticket disasters,” while overlooking the needs of low-income communities after smaller-scale events, such as flooding in 2017 that caused millions of dollars in damage to a small town in the Finger Lakes region of his state.

“I’m sick and tired of seeing people building multimillion-dollar mansions on the beach and then getting FEMA assistance, while people in rural areas don’t get squat,” he said during the hearing. “We’ve got to change that.”

The second storm

On March 25, 2021 — one week after Alabama’s request for FEMA aid in Fultondale was denied — another storm swept through the state. A series of tornadoes killed six people and destroyed more than 200 homes. The longest twister stayed on the ground for 80 miles, with winds reaching up to 150 mph. Fultondale was largely spared, but other parts of Jefferson County were hit, including Birmingham, where 42 homes were damaged.

Ivey again requested aid from FEMA, this time for eight counties, including Jefferson County. With damage stretching across the state, Biden soon issued a disaster declaration, opening the way for residents to apply for individual assistance from FEMA.

Although far fewer homes were damaged in Jefferson County during the March storm than in the January one, those who had been hit in the second storm now had a path to federal aid.

Martín, the Brookings Institution researcher, has found that survivors of larger catastrophes may fare better because they receive more government assistance. He believes federal and state governments should work together to close the current gaps in supporting people in need.

“If there isn’t a state assistance program that helps people recover, then why isn’t there a federal assistance program to cover even these smaller cases?” he asked.

Bullard, the Texas Southern University professor, said that nonprofit aid is an inadequate alternative.

“It places the burden of finding assistance on the shoulders of charity,” he said. “That’s the disparity. There’s no way that a charitable network or organization can somehow provide the kinds of resources that the government, taxpayers can do.”

Justin McKenzie, chief of the Fultondale Fire Department, said some residents whose homes were destroyed in the January storm could not afford to rebuild without FEMA help and had to leave Fultondale to start over. It occurred to him that if that first tornado had stayed on the ground longer, crossing county lines and harming more people, Fultondale’s residents would have had a better chance of getting aid.

“We don’t want anybody else to get hurt,” he said, “but if it would have done that, it would have opened up the funds.”

'Starting to live again’

For the Arizaga family, remaining in Fultondale grew harder as time passed. There were reminders of Elliott everywhere, at the school, the shopping center and the park where the boys used to play in a creek.

Saraid missed her conversations with Elliott, some lighthearted, but others serious. A few weeks before the storm, after several teenagers died in a car accident, she said he told her, “If something were to happen to you, I’d go crazy. I wouldn’t be able to live without you,” Saraid recalled. “I told him, ‘Don’t even say that, because I’d also go crazy without you.’”

The family has struggled to adjust. “We never, ever imagined that it would be our last night together, that our lives would change so drastically,” Saraid said. “It’s almost like we’re starting to live again right now as if it was our first day alive…. We’re learning how to live without him.”

By spring, the family had made the decision to leave Fultondale.

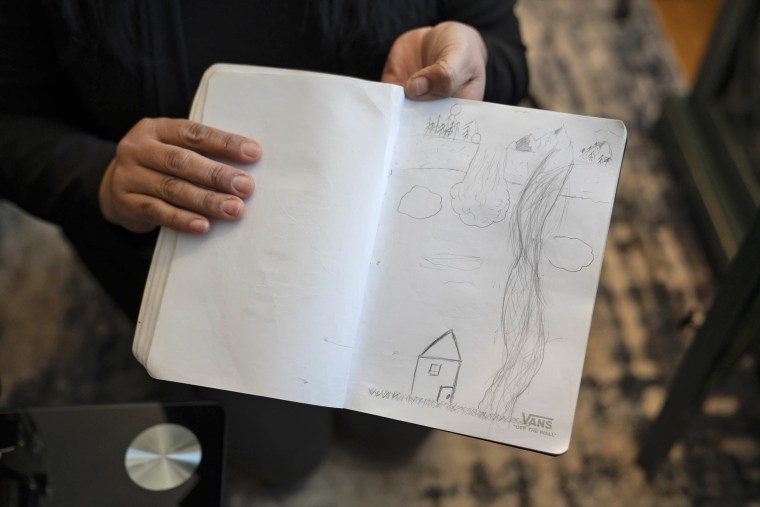

They used some of the more than $100,000 collected in GoFundMe donations for a down payment on a home in Adamsville, about 20 minutes away. In their living room, they built a shrine to Elliott in a glass cabinet, displaying his sketchbook and the trumpet he looked forward to playing in church.

On the anniversary of the tornado, Saraid returned to Oak Street.

Cars with shattered windshields were still parked there. One of their neighbors was living in a camper, waiting on donated timber he needed to rebuild. Other homes were completely gone, reduced to grassy lots and concrete slabs strewn with debris. Saraid placed yellow flowers on the one that used to be their home.

Bracey Harris reported from Fultondale, Alabama; Joshua Eaton reported from Washington, D.C.

Methodology

To understand how often FEMA and the White House declined to approve direct assistance to survivors of natural disasters, NBC News analyzed Preliminary Damage Assessments published by FEMA between the fall of 2018 and the fall of 2021. Those were compared with a FEMA database of disasters that showed whether they resulted in awards through its Individual Assistance Program. We counted as “declined” only requests by governors that resulted in no award of individual assistance to any county. In some instances, governors requested aid for more counties than received it, but those were not included in our analysis.